DNA testing on the remains of 64 children sacrificed at the Maya city of Chichén Itzá more than 1,000 years ago has given researchers extraordinary insights into the ritual killing practices of the site’s pre-Columbian inhabitants and their ties to the Maya people who live in the area today.

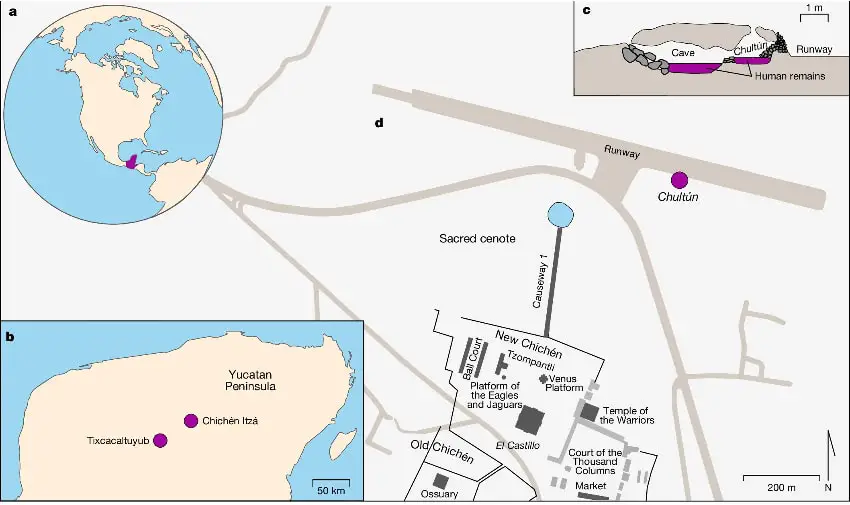

In 1967, a team of archaeologists discovered the remains of more than 100 young children in a chultún, or underground cistern, near the Sacred Cenote at Chichén Itzá, located in the state of Yucatán. While a chultún was typically used to store fresh water, this one had been repurposed as a funerary chamber.

Several decades after the discovery, DNA was extracted from the skulls of 64 of the children, most of whom were buried in the cistern between 800 and 1,000 AD, when Chichén Itzá was a major political, cultural and religious center.

The results of the DNA testing came as a great surprise to an international team of researchers, who revealed in an article in the journal Nature that all of the sacrificial victims found in the chultún were boys, and among them were two sets of identical twins as well as other brothers, some of whom may have been fraternal twins.

“We kept rerunning the tests because we couldn’t believe that all of them were male,” said Rodrigo Barquera, a Mexican archaeogeneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI-EVA) in Germany and lead author of the study published in Nature on Wednesday.

“It was just so amazing,” he added.

Why were twins among the child sacrifice victims?

In their paper, the international researchers wrote that in contrast to human remains found in the Sacred Cenote at Chichén Itzá, those discovered in the chultún were all boys, “demonstrating a strong preference for the ritual sacrifice of male children in this context.”

“Genetic analysis also showed the presence of related individuals within the chultún, including two sets of monozygotic twins and nine other close relative pairs. As such twins occur spontaneously in only 0.4% of the general population, the presence of two sets of identical twins in the chultún is much higher than would be expected by chance,” they said.

“Overall, 25% of the children had a close relative within the assemblage, suggesting that the sacrificed children may have been specifically selected for their close biological kinship.”

The researchers noted that twins are “especially auspicious” in Maya mythology and that “twin sacrifice is a central theme in the sacred K’iche’ Mayan Book of Council, the Popol Vuh.”

In that book, the twins Hun Hunapu and Vucub Hunahpu descend into the underworld and are sacrificed by the gods following defeat in a ballgame, they explained.

Hun Hunapu’s head is subsequently hung in a calabash tree where — in an episode akin to something you might read in a magical realism novel — it impregnates a young woman who gives birth to another set of twins, called Hunapu and Xbalanque.

“These twins, known as the Hero Twins, then go on to avenge their father and uncle by undergoing repeated cycles of sacrifice and resurrection to outwit the gods of the underworld,” the researchers wrote.

“The Hero Twins and their adventures are amply represented in Classic Maya art and given that subterranean structures were viewed as entrances to the underworld, the twin and relative sacrifices within the chultún at Chichén Itzá may recall rituals involving the Hero Twins,” they said.

Barquera told Reuters that he and his fellow researchers “think that the people from Chichén Itzá were trying to symbolically replicate the Mayan mythological stories and the representation of the twin heroes in this ritual burial.”

“For Maya, and Mesoamerican cultures in general, death is the ultimate offering, and as such, sacrifices bear high importance to their beliefs system,” he added.

Barquera also noted that while “ritual sacrifice was a common practice among ancient Mesoamerican populations, … the biological relationships between the sacrificed individuals had not been described before.”

How were the boys killed?

The researchers haven’t been able to determine how the boys were sacrificed, but they have concluded how they didn’t die.

“There are no cut marks or evidence of trauma, which tells us how did they not die,” Baquera said. “But we have not found a cause of death for them yet,” he added.

The discovery that boys were sacrificed at Chichén Itzá contradicts a once popular idea that the ancient Maya people preferred females, and especially young virgin women, for ritual killings.

From researching a centuries-old pandemic to uncovering sacrificial practices

Close to 20 years ago, Barquera was aiming to discover the genetic legacy of a 1545 Salmonella enterica pandemic that killed large numbers of Indigenous people that lived across the territory that is now known as Mexico.

To do so, he and his colleagues needed to compare the DNA of pre-Columbian remains with that of people born after the calamity, the New York Times reported. The skulls found in the chultún fell into the category of pre-Columbian remains, and in 2015 Barquera’s team received permission to destroy small sections of the craniums to extract and sequence DNA.

Analysis of the DNA extracted from the petrous portion of temporal bones of the skulls allowed the researchers to determine the genetic relationships between the sacrificial victims, and consequently theorize about why the twins and other siblings were killed.

“We found two pairs who were so similar they could only be identical twins, and at least three more who were full siblings. They could have also been twins, but fraternal twins, coming from two different egg cells,” said Kathrin Nägele, another MPI-EVA archaeogeneticist and co-author of the study published in Nature.

“This is the first time we are able to confidently identify identical twins in the archaeological record,” she said.

Comparison between the sacrificial victims and modern-day Maya people

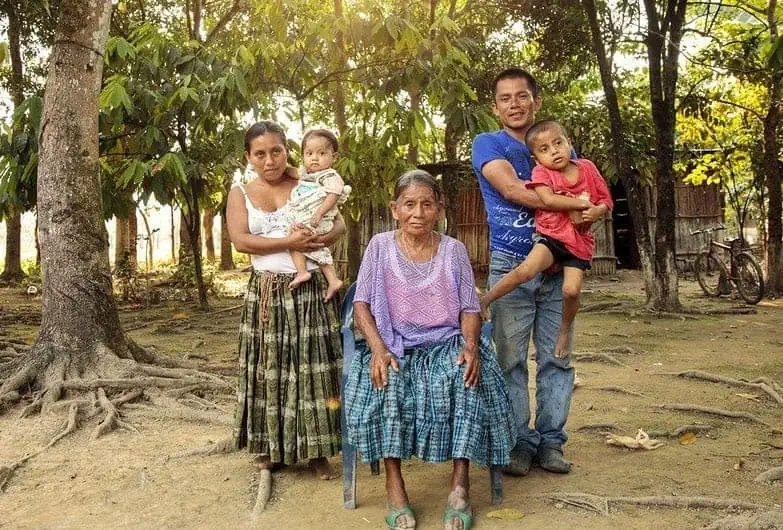

In addition to analyzing the DNA extracted from the skulls of the 64 boys, researchers compared the children’s genomes to those of 68 present-day Maya inhabitants of Tixcacaltuyub, a town around 60 kilometers southwest of Chichén Itzá.

They also compared the DNA from the skulls to “other available ancient and contemporary genetic data from the region,” according to the paper published in Nature.

Those comparisons uncovered “long-term genetic continuity in the Maya region,” the paper said.

The comparisons also revealed “allele frequency shifts in immunity genes, … specifically an increase in HLA-DR4 alleles which provide greater resistance to Salmonella enterica infection,” the researchers said, noting that said infection was “the causative agent of an enteric fever … associated with the 1545 cocoliztli pandemic.”

Jaime Awe, a Belizean archaeologist who specializes in the ancient Maya and is a professor at Northern Arizona University, told The New York Times that the comparative DNA analysis provides “clear proof” that the residents of Tixcacaltuyub “are descendants of the folks that developed one of the world’s most accomplished civilizations.”

Barquera, who along with a few colleagues traveled to Tixcacaltuyub to present their findings at local schools and share them with the 68 study participants, told the Times that the Maya residents of the town were thrilled to receive confirmation of their genetic links to the people who built and occupied Chichén Itzá long before the arrival of the Spanish.

He said that Maya people who live close to ancient cities such as Chichén Itzá often pose this question to outsiders: “‘Why do you have so much respect for the people who built these sites, and then treat the Indigenous people who live around them like inferiors?'”

Barquera added that the Maya people can now say: “Look, we’re related to the ones who made these pyramids. So maybe stop being racist toward us.”

The archaeogeneticist previously conducted a genetic study that provided fascinating insights into the lives of three African men believed to be slaves, who were buried in colonial Mexico City nearly 500 years ago.

With reports from Reuters and The New York Times