DNA testing has allowed a Mexican graduate student and his German adviser to obtain a fascinating insight into the lives of three African men believed to be slaves who were buried in colonial Mexico City almost 500 years ago.

Rodrigo Barquera, an archaeogenetics student at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, and his adviser Johannes Krause extracted DNA from the teeth of three male skeletons found in the early 1990s when workers were excavating for a new subway line.

They came across a long-lost burial ground that had been connected to a hospital for indigenous patients that was built shortly after the Spanish conquest of Mexico in the early 16th century.

The San José de los Naturales Royal Hospital and its cemetery were located in the center of the fledgling colonial city near where the Line 8 Metro station San Juan de Letrán now stands.

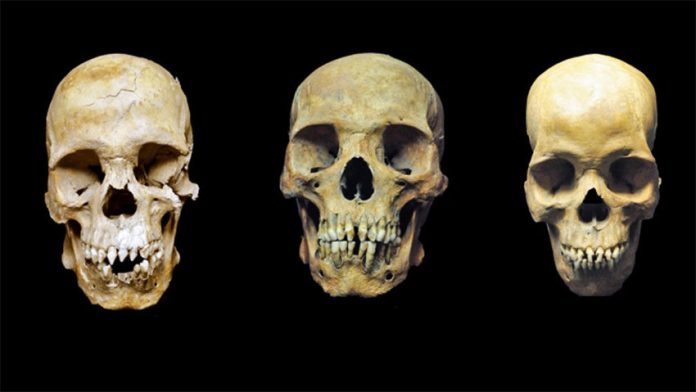

Three skeletons excavated at the colonial-era cemetery stood out because their teeth were filed decoratively, alerting archaeologists that they weren’t local indigenous people. It was concluded that the remains most likely belonged to slaves from West Africa but without more evidence they couldn’t be sure.

Now, however, Barquera and Krause have concluded that the individuals were among the first generation of African slaves to arrive in the Americas. Via a DNA analysis of their teeth, the researchers were able to conclude that all three men had ancestry from West Africa, although they couldn’t pinpoint which country or tribal group they came from.

According to an article by the researchers published on Thursday in the journal Current Biology, chemicals in their teeth – which retain a signature of the food and water they consumed in their childhood – were consistent with West African ecosystems.

Barquera and Krause also studied the whole skeletons of the probable African slaves, all of which are held at the National School of Anthropology and History (ENAH) in Mexico City. ENAH researchers assisted Barquera and Krause in their analysis.

“We studied their whole skeletons, and we wanted to know what they were suffering from, not only the diseases but the physical abuse too so we could tell their stories,” Barquera said. “It has implications in the whole story of the colonial period of Mexico.”

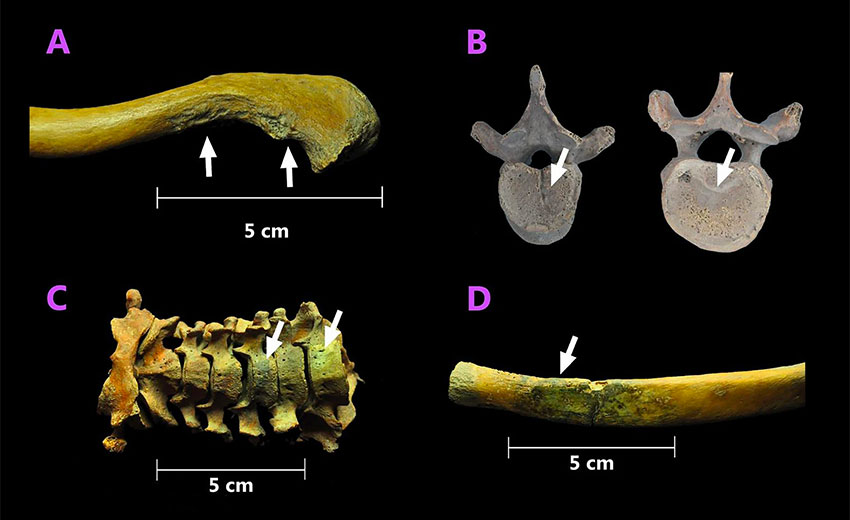

The researchers concluded that the three men were in in their late 20s or early 30s when they died. Two of them may have suffered from malnutrition and anemia as the bones in their skulls had thinned, a phenomenon consistent with those conditions. The skeleton of one of the malnourished men indicated that he had survived several gunshot wounds.

“You could see that the bone was stained with a copper greenish pigment because the bullets stayed in the body of this individual until he was dead,” Barquera said.

The skeleton of the third man showed signs of severe stress, most likely from arduous physical labor. Signs of abuse, including a poorly-healed broken leg, made it more likely that the men were enslaved rather than free, Krause said.

Through a genetic analysis of the microbes in their teeth, the researchers found that the two men with malnutrition carried pathogens linked to chronic diseases. One carried the hepatitis B virus and the teeth of the other man had traces of the bacteria that causes yaws, a tropical disease related to syphilis.

The microbes carried by the men most closely resembled African strains. One hypothesis is that the slaves were infected at home before their voyage to the Americas. Another, put forward by Ayana Omilade Flewellen, a University of California archaeologist not involved with the study, is that they picked up the microbes on a crammed slave ship as they made their way to the new world.

Krause said that the discovery of the diseases carried by the men is direct evidence that African slaves introduced new pathogens to the Americas in the same way European colonizers did.

“We are always so focused on the introduction of diseases from the Europeans and the Spaniards that I think we underestimated how much the slave trade and the forceful migration from Africa to the Americas contributed also to the spread of infectious diseases to the new world,” Krause said.

Although they were able to determine that the slaves suffered from a range of ailments, the researchers could not definitely conclude what killed them.

Although the skeletons didn’t detect DNA that showed that the men had been infected with smallpox or measles, it is possible that they died of those diseases during epidemics that afflicted the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

Source: Science Mag (en), The New York Times (en)