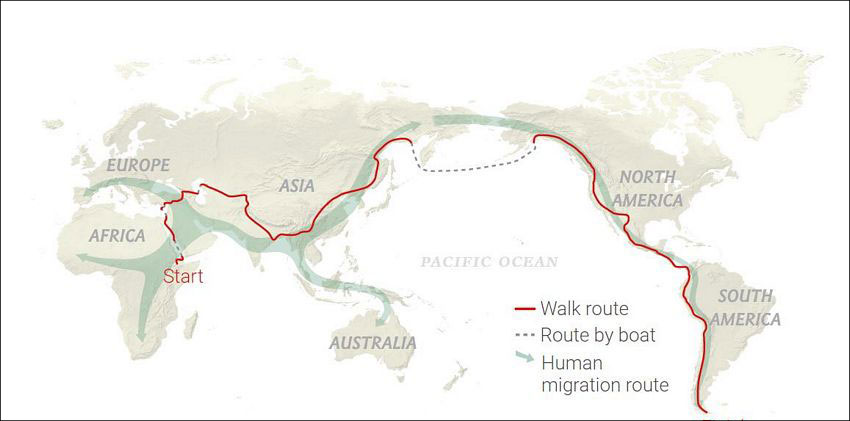

Several years ago National Geographic magazine published what struck me as an absolutely astounding story. It stated that every single human being on the face of the earth today is a descendant of a rather small number of people (perhaps only a few hundred) who emigrated out of Africa around 60,000 years ago, embarking on a trek that would quite literally take them to the very ends of the earth. This conclusion was based on advances in genetics and DNA samples taken worldwide.

The fact that we are all descended from Africans had impressed me, but I was especially interested in the fact that most of our ancestors had crossed the Bab Al Mandeb Strait over to the Arabian Peninsula and worked their way north through what is now Saudi Arabia.

This resonated with my own 13-year study of Saudi Arabia’s caves. I knew that the principal sources for water and shelter (from heat, cold and especially from wind) along vast stretches of western Arabia are lava tubes: caves up to 20 kilometers long and 40 meters wide which are located (sometimes in great numbers) among the 80,000 square kilometers of lava fields near which many of those early forebears must surely have passed.

That map of mankind’s great migration must have impacted many people around the globe, among them a man named Paul Salopek, one of the world’s great journalists and two-time winner of the coveted Pulitzer Prize. Salopek really took the story of humanity’s long walk to heart.

Following clues provided by DNA studies, he mapped out a route all the way from Ethiopia to Patagonia — 33,796 kilometers — and proposed to walk all that distance (except for a couple of short stretches over water) during what he first imagined would take seven years of his life. That was seven years ago, and he has still not reached the halfway point on his odyssey.

Why did he want to do this?

“Long-term storytelling,” he replied. “It’s not an athletic event. … I want to examine the great issues of our day at three miles an hour … to watch the world around me and to get into people’s lives.”

Salopek started his journey in January 2013, crossed the Red Sea and, accompanied by a Bedu and two pack camels, slowly walked his way north through Saudi Arabia, always talking to local people, listening to their worries, hopes and dreams, and reporting short, fascinating dispatches every few days.

“I am on a journey,” he says. “I am in pursuit of an idea, a story, a chimera, perhaps a folly. I am chasing ghosts. Starting in humanity’s birthplace in the Great Rift Valley of East Africa, I am retracing, on foot, the pathways of the ancestors who first discovered the Earth at least 60,000 years ago. This remains by far our greatest voyage.”

“We know so little about them. … They straddled the strait called Bab el Mandeb — the “gate of grief” that cleaves Africa from Arabia — and then exploded, in just 2,500 generations, a geological heartbeat, to the remotest habitable fringe of the globe. Millennia behind, I follow.”

When I contacted the indefatigable walker, he noticed I was living in Jalisco and told me that he also had lived here:

“I grew up in Zapopan, on the fringe of Colonia Seattle,” he said. “I would go drop fishing lines down holes in Agua Azul Park to fish for rats. Took buses into the Barranca de Oblatos to go hunting with my neighbor Lalo’s hand-made flintlock. It was a fairly wild area back then. We used river stones as ammo and never hit anything. … My playgrounds were the guamuchil trees, garbage-strewn lots and lush green corn fields around the edge of the city. Some of my boyhood friends died young of curable diseases. We had fun.”

Salopek’s Mexican adventures didn’t stop there.

“Some years ago, I rode a mule from Douglas, Arizona, to Michoacán, down the spine of the Sierra Madre. A memorable journey.” The story of this 2,090-kilometer journey, which retraced the route traversed by Norwegian explorer Carl Lumholtz in 1890, is told — with reflections on Salopek’s boyhood in Mexico — in the June 2000 edition of National Geographic magazine.

In “Literature as Lucha Libre,” a lesson on writing for The American Scholar, Salopek reflects on a perhaps surprising aspect of his youth in Colonia Seattle:

“My greatest literary inspiration at this time was a comic book called Kalimán. Kalimán was a vaguely Sikh superhero in white tights who spoke Spanish. (These) adventures introduced the notions of cliffhangers and the second act. Kalimán was always going into trances, slowing his metabolism down into deathlike comas. Even then, as a child, this struck me as the perfect Mexican super power, a defense against 1 billion years of fatalism.

“Soon I was drawing my own. My cartoons featured schizoid child geniuses who lived on desert islands and a race of woolly mammoths who lived underground. I rented out my comics, thus discovering editing and royalties. Kids in huaraches paid me 20 centavos to sit on the dirt sidewalk outside my house, page through stacks of my crude narratives and offer mostly negative textual analyses.”

I asked Salopek how much his years in Mexico had influenced his life.

“Mexico informs everything I do,” he replied, “because it’s my childhood. And like childhood, that Mexico of mule-plowed fields is fading fast. Maybe it’s gone. I grew up between 1870 and 1970. For better or worse NAFTA closed that gap. ‘El México que se nos fue’ and all that. It occurs to me from time to time that maybe I’m out looking for the older Mexico elsewhere. Don’t we all do this? And isn’t it always a lunatic enterprise?”

While examining the great issues of our day at three miles an hour, Salopek also has time to appreciate nature as some of our ancient forefathers must have. His latest dispatch comes from the hills of India’s northeastern frontier. He had been told that “in this place, there is nothing.”

Here are a few of Salopek’s comments on that “nothing”:

“In Umrangso, the tree frogs announced their love in the xylophone scales of bamboo wind chimes. I listened to gibbons rocket through the treetops along the Jiri River, dislodging showers of leaves and whooping like soccer hooligans. And everywhere, I overheard the hills speaking the sibilant dialects of unbounded water. The ionic hum of waterfalls. The white hiss of streams. The hard-knuckled rap of monsoon rain on roof tin. Even atop the highest ridges — where I expected nothing but damp wind — came the faint, quavering sigh of wild rivers far below.”

[soliloquy id="101827"]

Paul Salopek’s dispatches are a delight to read. Some are pure poetry, some show us how people in the most remote places are resonating with problems that impact our everyday lives. An example is his story of Robin Naiding, mild-mannered headman of the Indian village of Baga Dima, who was affected by the global crisis of conscience about the use of plastic straws and decided to start making them out of bamboo, resulting in a business which has won the hearts of thirsty Indians in megacities like Delhi and Bangalore.

Salopek has logged over 10,000 miles on his storytelling project and after 18 months in northern India, is about to enter China. Some time ago it became clear to him that his odyssey was going to take far longer than the seven years he had originally projected. Instead of speeding up, Salopek decided to slow down. By now he had discovered that good journalism, like love and gourmet cooking, must never be rushed.

This is slow journalism, par excellence.

You will find Paul Salopek’s recent and earlier dispatches on National Geographic’s Out of Eden page.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.