In a unique opportunity, selections from an archive of Mexican cookbook manuscripts dating back to the 18th century are now available online thanks to a recent initiative in Texas.

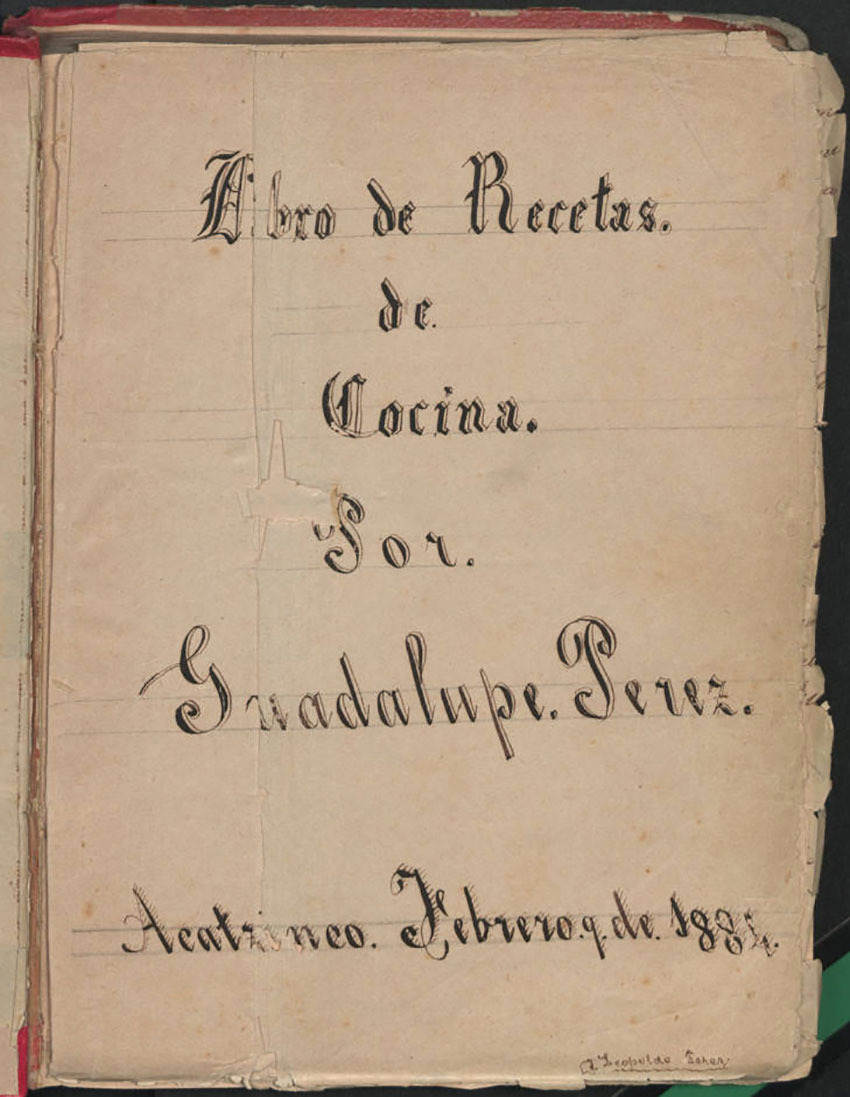

As of mid-February, 50 of the fewer than 100 manuscript cookbooks at The University of Texas at San Antonio’s Libraries Special Collections have been digitized for reading across platforms, from smartphones to tablets. The recipes reflect diverse culinary styles, regions and time periods in Mexican history, with the oldest volume from 1789 and the most recent from the 1970s.

“We try to be fairly broad in our selection,” said special collections librarian Stephanie Noell. “Pretty much every region is represented in our collection. … We try to make sure we pull from across the board, not just one specific region.”

The previously unpublished cookbooks are part of the overall Mexican Cookbook Collection of over 2,000 volumes at the university library. The core of the collection is the 550 cookbooks from longtime San Antonio librarian Laurie Gruenbeck’s personal collection, which she accumulated over three decades of traveling across Texas and Mexico and donated to the library in 2001.

Last year, food writer Diana Kennedy donated her personal research archives, which include the sole non-manuscript cookbook that has been digitized: a copy of the 1828 Arte nuevo de cocina y repostería acomodado al uso mexicano, a Mexican cookbook published in New York. Noell calls this book “incredibly rare.”

Cookbook manuscripts are also rare, Noell said. In most, she explained, “people would write down recipes and not anticipate [other] people would put them in a collection and preserve them for hundreds of years. They don’t come up very often. The ones we have are absolute gems.”

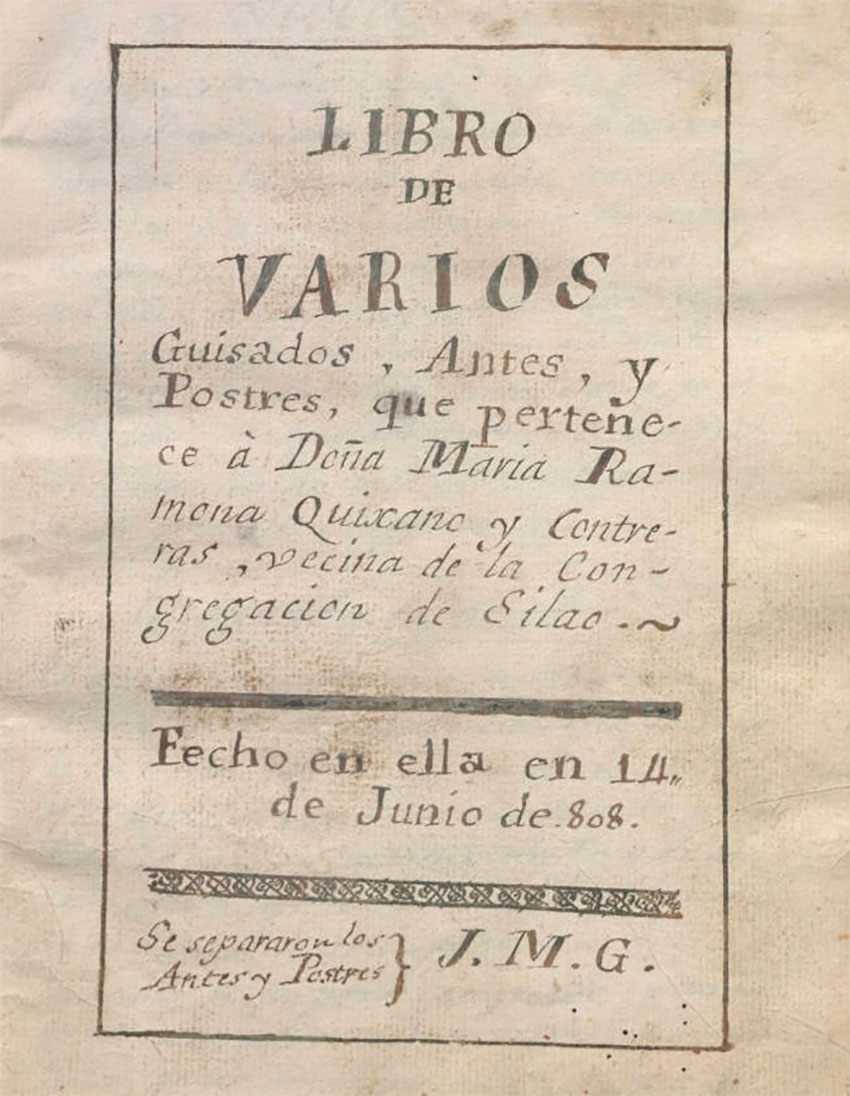

The two oldest — the 1789 volume from Jalisco and an 1808 manuscript from Guanajuato — are the only colonial cookbook manuscripts in the collection and the first to be digitized. The author of the 1789 cookbook wrote her name as “Doña Ignacita.”

“Of course, the older the cookbook, the harder it is to really determine who this person was,” Noell said. “There are sort of whole sets from the same family, a documentation of generations of a family. It really depends on the cookbook. Sometimes it’s just a first name.”

Even if the authors’ identities might be unclear, there are some clear surprises in the recipes.

“One of the first surprising discoveries was turtle soup, which I hadn’t seen in a cookbook before,” Noell said. Another surprise, she said, was “brains in fish sauce,” written in English as part of a recently digitized bilingual cookbook.

In some of the 19th-century cookbooks, there are “a lot of tamal recipes” that use rice instead of masa, Noell said. “I have not had tamales with rice filling,” she said. “Now they’re on my bucket list.”

Digitizing these historic volumes is a complex and ongoing process. Library staff must use an overhead scanner, not a flatbed one. An overhead scanner will “keep everything in place with the text visible and not squash the book,” Noell explained, noting that individual texts present specific challenges, such as the 1789 cookbook, which has a torn cover page and some curled edges. The digitized cookbooks are then uploaded to a database.

The archive is a culinary excursion through Mexican history, representing a gradual blending of European and indigenous cuisine, such as in gazpacho recipes.

“What you see in a lot of early cookbooks is a heavy European influence,” Noell said. “But in the 18th century, really only within one decade or so that the [1789] cookbook was written, you start seeing gazpacho with tomato, a New World ingredient. That’s not how it was made in the old country.”

She notes, also, that “a lot of early cookbooks are very dessert-heavy. … Back in the 19th century, people really liked dessert. It’s a safe bet some [recipes] were good.”

She likes a relatively more recent recipe, from a 20th-century cookbook written by a German immigrant. “He has a five-minute flan in there,” she said. “I was blown away. … How can I make flan in five minutes in a pressure cooker?” And, she said, “some cookbooks have a whole section for bebidas. You can get some great drinks.”

Noell said that she “would like to get as many of these public domain cookbooks digitized as possible.”

“It’s a really fascinating collection to go through,” she said. “There’s something different every time you go in.”