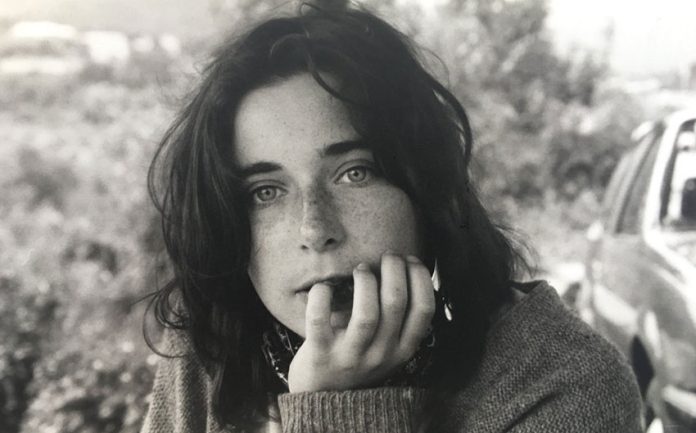

Last week saw the unfortunate death of Jo Tuckman, a journalist and Latin America correspondent for the U.K.’s Guardian newspaper, widely celebrated as a passionate and tenacious reporter whose writing signified a deep-seated love of Mexico.

Tuckman embodied a style of journalism that had been falling out of fashion over the past 20 years, one that is distinctly anthropological and that explores complex truth through personal stories. She leaves a posthumous legacy that provokes our ever-growing, reporting-by-number news conglomerates and that inspires a fresh belief in sensitive and immersive journalism.

Arriving in Mexico in 2000, Tuckman found herself reporting on some of the most politically tumultuous years of its existence, documenting the transition to democracy following 70 years of single-party rule. Those first years in the country went on to define her career as she continued to dissect complex political and social issues for a U.K. audience.

Some of Tuckman’s most notable contributions include stories about cartel violence, the expanding war on drugs, the persecution of fellow journalists, and the human rights abuses of indigenous peoples.

Jo Tuckman’s extraordinary ability as a reporter, however, was not limited to her bravery in confronting power, or even facing off criminals known for their violence toward journalists, but instead for the nuanced approach she adopted in her coverage. Tuckman’s approach was always centered around her fascination with stories and the people behind them, an inclination that many attribute to her background and education in complex social anthropology. The charm of her stories was always found in, and expanded out of, human interest, allowing her to find ways to engage readers in Mexico’s social and political happenings.

There was a recurring sensitivity throughout Tuckman’s work that allowed her to transition seamlessly from reporting on ruthless drug lords and untold violence to the unfortunate passing of Gabriel García Márquez, one of Latin America’s best loved authors, and his world-bending narratives of magical realism.

She could one day be confronting political corruption and embezzlement and the next, be exploring a recently discovered mammoth trap as evidence of prehistoric hunting methods. Genre-hopping journalism of this kind can be mind-numbingly jarring, inhibiting the sensitivity required to dissect and understand effectively the story at hand, but Tuckman constantly seemed to be energized by the diversity and irregularity of her work.

This energy that Tuckman brought to her reporting sets the standard for what foreign journalism in Mexico and Latin America should be, her expansive portfolio woven throughout with lessons about the complex responsibilities involved with the profession. At its core, Tuckman’s career in Mexico exemplifies the importance of connection to one’s country of reporting and a genuine love for its people.

Jon Bonfiglio, Latin America correspondent for TalkRadio, claims that “her coverage of abuses toward vulnerable Mexicans was angry, loud, always passionate. She wasn’t just reporting on Mexican society, she was a part of Mexican society.”

It was this intense relationship that gave her the profound motive and ability to help a foreign and disconnected readership interact with the Mexican struggle.

Far too often, foreign journalists deployed to areas experiencing complicated, and often destructive, political and social problems lack the incentive and understanding to portray the inhabitants with the nuance that their situation deserves. These are often country-hopping, career journalists that score points “back home” by standing in front of impoverished inhabitants, reporting on, and looking down at, corruption in democratic infancy, and generally helping the Anglo-Saxon reader feel a little happier about his situation.

Meaningful foreign correspondence never emerges from this hastily concocted formula, in fact, for real reportage that accurately distills truth across cultural boundaries. Foreign correspondence must become local correspondence. This is the legacy that Jo Tuckman leaves, a journalism that is invested, loved, nurtured. Tuckman never belittled Mexico because there were always stakes, risk, an understanding that to portray inaccurately the people of Mexico would fundamentally undermine her wide-eyed wonder and admiration of the place that had become her home.

Even when Tuckman fell ill and was told to return to the U.K. for medical care, her induction from foreign journalist to Mexican citizen led her to respond “no, this is my home.” She was accepted by Mexico and, importantly, had accepted Mexico herself; this is the cornerstone of avoiding reckless parachute journalism.

Perhaps, in one of her final stories, an interview with former Bolivian president Evo Morales who was embarking on his exile in the Mexican capital, she would have remembered her own first days in the country, and realized how far she had come.

Jack Gooderidge writes from Campeche.