Before I moved to Mexico, I had never heard of homeopathy, an approach to medicine developed by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann in 1796.

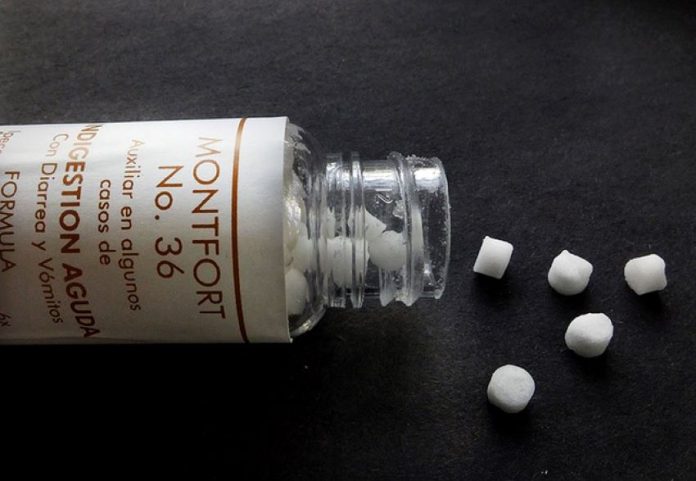

After living here only a few months, I found that every time I had a cold, someone would say, “You are getting a gripa [a cold]? You should take Aconitum,” or “That bruise will feel a lot better if you take Arnica,” and then they would hand me a bottle of little sugar pills soaked in alcohol, popularly known as chochos.

So I learned that my friends, relatives and neighbors claimed they could cure anything from a stomachache to a bone spur (I kid you not) with homeopathy — all except people with a medical degree. They, on the contrary, thought the whole thing was hilarious:

“Homeopathic Aconitum napellus is made by putting one drop of extract of highly toxic wolfsbane (matalobos) into a liter of potable alcohol and agitating the bottle vigorously. Then the homeopath takes one drop from that bottle and puts it into another liter of alcohol and shakes that up and so on … Ho, ho, ho, how could it possibly work?”

Homeopaths reply that the vigorous agitation creates in the alcohol a molecular memory of the presence of the wolfsbane and that this grows stronger, not weaker, with every new dilution and shaking. The chochos themselves don’t cure anything, they say, but merely tell the mind what it needs to cure, unlike modern medicines, which aim to physically affect blood, tissues, bones or whatever.

My relatives and friends with medical degrees (including the head of a nationwide chain of pharmacies) typically pooh-pooh homeopathy right up to the day that one of their children gets deathly sick with the worst case of diarrhea known to humanity and — in utter desperation — they resort to the chochos handed to them by a neighbor. After that, a bottle of Montfort 36 (a mix of five homeopathic remedies) quietly appears at the back of their medical cabinet, well hidden from prying eyes.

Just why chochos often work is a question I have thought about for three decades, in the course of which I somehow contracted salmonellosis, which kept coming back year after year with devastating consequences. Each time I went to a “proper western MD,” he or she would prescribe antibiotics, which would apparently rid me of the infirmity; but it would return the following year with a vengeance until I finally said to my IMSS doctor, “Please tell me why this keeps coming back,” and he ordered a study to be carried out.

After a thorough examination, the doctor told me, “The salmonella bacteria are hiding in your spleen where antibiotics can’t get to them. That’s why the salmonellosis keeps coming back. Most of the time those bacteria will cause you no problem, but you’ll be able to see their presence in every sample of your blood, even when you are feeling fine. I don’t know of any way to get rid of them completely, so you are going to face future attacks again and again.”

When “proper medical science” fails I, like so many Mexicans, turn to chochos. So I made an effort to find myself a respected university professor of homeopathy. He said he could solve my problem and put me on a special treatment: two different kinds of chochos to be taken at different times of the day over a period of several months, two weeks on and two weeks off.

“Go get a blood test once a month,” said Dr. Roberto Ibarra. “When your salmonella count goes down to zero, you will know the bacteria are gone for good.”

Now, that’s what I like. A bit of hard lab science to balance the mumbo-jumbo.

To make a long story short, each month the blood samples showed less salmonella bacteria until the number actually reached zero … and I’ve never had another attack of that miserable malady.

I kept wondering why homeopathy sometimes works so well until I came upon a report describing an experiment in “placebo surgery” carried out in 1994 by Doctor J. Bruce Moseley, associate professor of orthopedics at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

Ten men with the same painful knee problem were taken into the operating room for surgery and the next day sent home with crutches and a painkiller. Two of those men underwent standard arthroscopic surgery (flushing with a saline solution and scraping of the knee joint), three got only the flushing and five got nothing more than small cuts in their skin. To add realism to the simulated operations on the latter, a tape recording of the real procedure was played while these five patients were under sedation.

To the great surprise of Dr. Moseley, the results inside the knees of all 10 patients were identical. The patients who had not been operated on felt great and were up and walking around just like those who had had the surgery — and their knees are pain-free even today.

This incident led researchers to look upon the placebo with new eyes and considerable curiosity.

It seems to me these people were cured by what is popularly called the immune system but which might be better named the body’s self-healing system. It appears that the simulated operation — with all the drama and trappings of the real thing — gave the following message to the self-healing system: “Attention please! I have a problem in my knee. Fix it!”

I propose that the “molecular memory” of Aconitum in the chocho presents a similar message: “Attention please! I have symptoms similar to those caused by what’s in this chocho. Fix me up!”

This mechanism should be familiar to all of us. If not, it soon will be when you get your Covid-19 vaccination: “Pay attention, body! I want you to cure me of anything resembling the stuff they just injected me with!”

As far as I can see, vaccinations are a great example of the often-repeated homeopathic principle of “Like cures like.” Stimulate the body’s self-healing system, and it might just heal you … without the need to take expensive drugs with a five-mile-long list of appalling side effects. Let’s have more studies of placebos for better health!

The curious case of the kneecap operations, by the way, led to the formation of the Harvard Placebo Study Group in 2001. You can follow some of their fascinating discoveries in the documentary film “Placebo: Cracking the Code.”

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of “A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area” and co-author of “Outdoors in Western Mexico.” More of his writing can be found on his website.