Harvard University evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman grew up encouraged to lead an active lifestyle, from hiking to cross country skiing. Yet he was amazed to experience the long-distance running feats of the Tarahumara, or Rarámuri, indigenous community in Mexico while doing field work in the Copper Canyon in 2012.

Just as amazing was an insight he gained from an elderly Tarahumara runner. When Lieberman asked how he trained to run such long distances, the man did not understand the concept of training and replied, “Why would anybody run if they don’t have to?”

“It was such a great question,” Lieberman recalled. And it was the genesis of his new book, Exercised: Why Something We Never Evolved to Do Is Healthy and Rewarding. “It suddenly zapped me that it would be a fun topic for a book,” he said, “the natural history of exercise being a kind of weird modern behavior.”

Lieberman studied biology and anthropology as a Harvard undergraduate. He combines the two fields in his work today. Although he does much of his research in Kenya, he traveled to Mexico almost nine years ago to learn more about the Tarahumara after reading Christopher McDougall’s bestselling book Born to Run.

“The Sierra Tarahumara is so beautiful and stunning,” he recalled. “It’s one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever had the opportunity to visit.”

Lieberman observed traditional Tarahumara running events such as the rarajipari — a combination of an ultramarathon and a ballgame — and the ariwete, a 25-mile run for young women involving the pursuit of a hoop. At one rarajipari, he enjoyed a communal meal of soup, tortillas and chiles and drank pinole, a roasted ground maize beverage. During this particular event, which lasted an entire December day, he joined one of the competing teams, led by champion runner Arnulfo Quimare.

“I asked everybody questions about their running,” he said, including “how they trained. Nobody seemed to understand that word. [The translator] said, ‘This guy [Lieberman] runs five miles every morning to get ready for running,’” which prompted the elderly Tarahumara man’s disbelief.

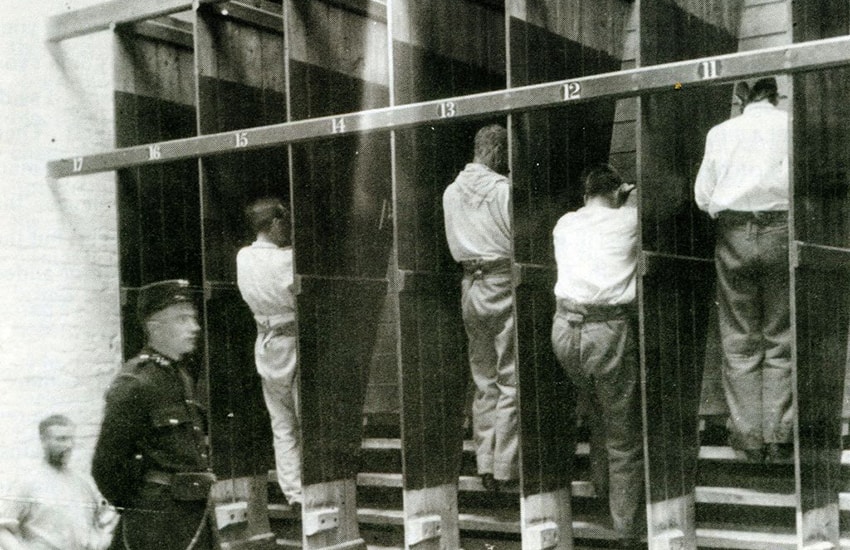

Exercise, Lieberman notes, has become part of western culture. Consider the treadmill, which he follows in the book from its antecedents in the Roman Empire to its use as a Victorian-era punishment for criminals such as Oscar Wilde to its ubiquity in gyms today.

“I can’t think of anything less fun,” Lieberman said. “So many people exercise on treadmills. They can’t be enjoying themselves. They watch a movie or show, a podcast.” He then adds, “There’s nothing wrong with it.”

Yet he is concerned about the approach that many people have toward exercise, whether it’s at a gym, on the treadmill or through an Ironman triathlon.

“People are ‘exercised’ about exercise,” he said. “They are confused about its mission and myth. A lot of it stems from medicalization and commercialization. It’s a very unusual activity; it’s not so easy.” And, he added, “Not everybody likes the topic. A lot of people find it a very irritating thing.”

At one end of the spectrum, there are elite athletes who train hard for intense competition that would intimidate many others. Lieberman explored such types of competition by going to the Ironman World Championship in Kona, Hawaii, before his trip to Mexico and by attending a mixed martial arts fight in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

On the other hand, there’s a perception of exercise as a necessary but unpleasant way for weekend warriors to get fit and shed extra pounds. The book’s publication, delayed by the Covid-19 pandemic, came out around New Year’s Day, when many traditionally make fitness resolutions.

“If you somehow don’t like it,” he said, it’s assumed there’s “something wrong with you, you’re lazy. It’s normal to want to avoid unnecessary exercise. People are made to feel bad about it, that there’s something wrong with them if they don’t go for a run or to the gym.

“It’s totally normal for human beings like the Tarahumara and everybody else not to go to the gym and lift weights whose sole function is to be lifted, to run five miles in the morning to stay fit. People overwhelmingly think it’s crazy — like the guy who asked me that question.”

Lieberman urges readers to find a middle ground: “We need to be more compassionate toward each other, understanding, less judgmental about each other.”

Although he understands the unpleasant side of exercise, he urges people to take it up in some form. The key is to “make it necessary, make it fun,” he said.

“School is enjoyable, and also required. I think we should treat exercise the same way, [whether it’s] “walking with a friend, going dancing, running with some friends, playing a game of soccer, engaging people. The better we do that, the better we will all be.”

That also goes for the elderly.

Lieberman cites a 1986 study of Harvard alumni by Dr. Ralph S. Paffenbarger Jr., that found that in their 20s, 30s and 40s, subjects who were more physically active had a 20% lower death rate than their nonactive peers. By the time subjects were in their 70s and 80s, the more physically active individuals had a death rate 50% lower than those who were not.

“As we get older, physical activity becomes more important,” Lieberman said. “We evolved not just to live to be grandparents but active grandparents — hunt, gather, grow food to provide for our children and grandchildren.”

For seniors today, he said, the active lifestyle is threatened by retirement — “a very modern Western concept” that historically did not apply to hunter-gatherers. “Physical activity is healthy,” he said. “It keeps us from senescing.”

He said that the Tarahumara, in general, “stay healthy as they age.”

“They are very physically active people,” he said. “Traditional Tarahumara are living a very healthy lifestyle for the most part.”

The average Tarahumara individual takes between 15,000 to 18,000 steps a day, well over twice the 4,000 steps a day for the average American. “Most Americans drive to the supermarket,” Lieberman noted. “They use a shopping cart; they don’t carry anything.”

In contrast, he said, “the Tarahumara are farmers … They don’t have machines, they don’t have cars, they don’t go to stores to get food.”

The tens of thousands of walking mileage logged by Tarahumara individuals are made “every day, all their lives,” Lieberman said, including on weekends, and are supplemented by other types of physical activity such as carrying and digging. He cautions against adopting a monolithic, stereotypical view of the Tarahumara as universal super-runners.

“Most Tarahumara do not run long distances,” Lieberman said.

He suggests that readers looking to exercise don’t need to run long, either.

“There’s no need to run a marathon,” he said. “There’s no need to do crazy stuff. A little bit goes a long way. My other advice is you don’t need a lot. Just a little bit has huge effects. Just a little bit has huge benefits.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.