For years, I had heard rumors of a place in Guadalajara called Salud Digna, where people of scarce economic means could get an eye examination and a good pair of glasses for a price they could actually afford — and for years, I had wondered about the story behind it.

As I happened to need a new pair of glasses, I looked up the Salud Digna website and discovered that they offered a lot more than eye examinations. A test to determine my blood type would cost me only 55 pesos, and an X-ray of my elbow would run me no more than 180.

Such services required an appointment, which I could easily set up via WhatsApp, but an eye examination — which is free, by the way — required no appointment of any kind.

A few days later, my friend Rodrigo, who also happened to need new glasses, drove me to one of Salud Digna’s four centers in Greater Guadalajara.

I must confess I imagined this clinic would look a bit like a soup kitchen with a long line of weary down-and-outers patiently waiting outside. In reality, there were no lines, neither outside nor inside, thanks to an efficient reception system that quickly had us heading for the optometry area.

Everything we could see was clean, sparkling and modern … as were the doctors, nurses and patients — the latter a mix of people who looked to me as if they came from all levels of society.

“A soup kitchen, this is not,” I commented to my compañero.

We waited for our names to be called in front of a big display announcing that Salud Digna now had over 70 centers like this one, all across Mexico and even in the United States, and that they care for 6.5 million people per year.

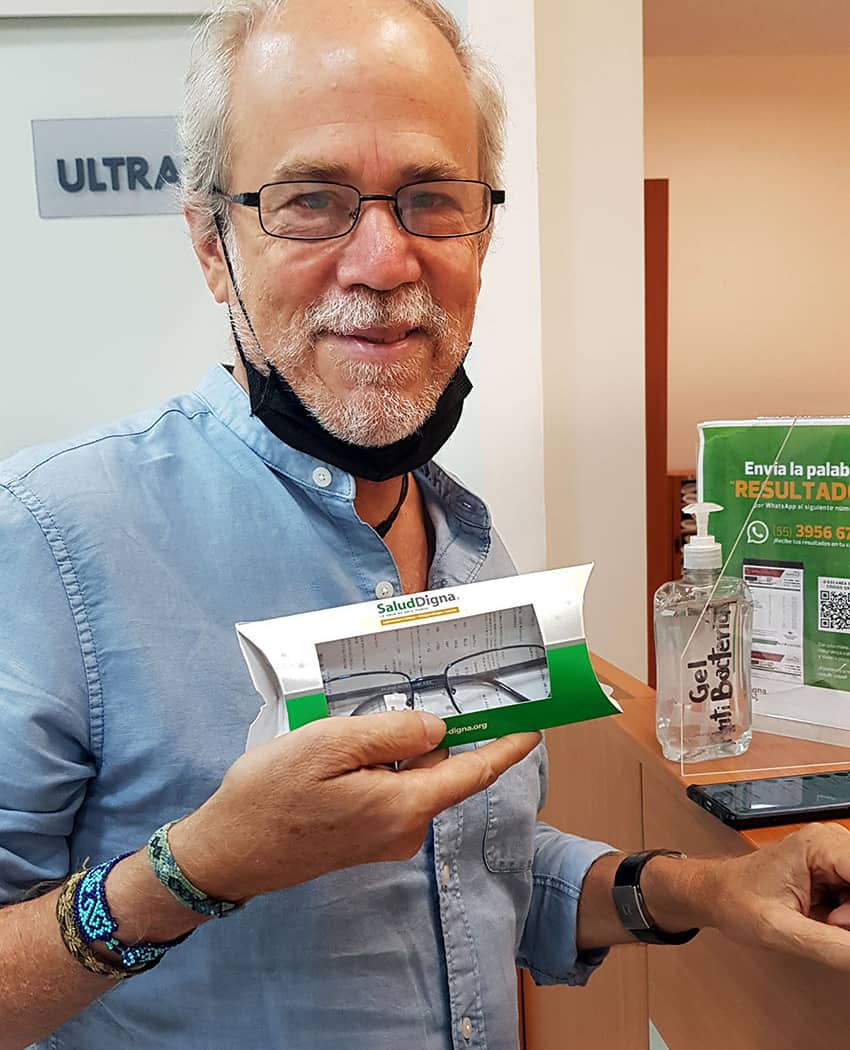

A friendly optometrist checked my eyes, using what seemed to me very modern equipment. In no time, I was picking out frames for my new bifocals, which cost a total of 480 pesos and would be ready in a week.

Rodrigo was able to pick up his uncomplicated glasses on the spot. He had also taken advantage of their standard offer of a second pair of glasses for half price. “So,” said Rodrigo,” I got an eye examination and two pair of glasses for 290 pesos. Not bad!”

Salud Digna (Health with Dignity) is a nonprofit organization, the brainchild of Mexican meat czar Jesús Vizcarra Calderón, who heads up SuKarne, the biggest exporter of beef, pork and chicken in Mexico. SuKarne slaughters about 1.7 million cattle per year and generates around US $2.8 billion in annual revenue.

“When I was 27 years old, one of my sons suffered a brain hemorrhage,” Vizcarra told the newspaper Milenio‘s Juan Pablo Becerra-Acosta in a long interview in 2015, “and I was impacted by the fact that great numbers of people in Mexico can’t afford health care of any sort.”

The future multimillionaire, it seems, got his start in the business world by selling lemons and guavas as a boy.

“My grandpa had trees filled with them,” he said. “They would have gone to waste, but I would fill a bucket with them and go around selling them with a couple of my friends. My next business venture was canicas (marbles). Playing marbles was the only thing on the mind of boys my age, so I decided to sell them marbles — not just any marbles, but the best quality marbles: las más bonitas [the most beautiful marbles]! So, after a while, everyone called me El Niño de las Canicas [Marble Boy].”

Not so many years later, Vizcarra applied his entrepreneurial skills to his parents’ cattle-fattening business and turned it into a leading company in the international meat industry. After that, he got interested in politics and was elected a senator in Sinaloa.

At the beginning of the new millennium, Salud Digna got its start as a backroom operation in Jesus Vizcarra’s office. The mobile health clinics, which he organized throughout his territory, were warmly received. The demand for these services grew to such an extent that he decided, in 2003, to create a fixed site offering diagnostic services.

Soon, Salud Digna centers were popping up in other parts of Sinaloa, and then all over Mexico. In spite of the fact that they charge less than a third of what private clinics get, they reached financial self-sufficiency in 2007, a fact that caught the attention of Harvard Business School, which offered Salud Digna as a case study to their students, citing one of Jesús Viscarra’s favorite sayings: “Don’t tell me why it can’t be done — tell me how it can.”

Most people I’ve spoken to who went to Salud Digna have found their services at least satisfactory, and several actually rated them excellent. Nevertheless, I found a number of complaints about them on the internet:

“They prescribed glasses for me,” said one man, “but I couldn’t see well with them.”

He went back to Salud Digna and they repeated his eye examination, concluding that their prescription was correct and that he should be able to see through his glasses, but he couldn’t.

I bring up this case because I think it highlights a weak point in the Salud Digna business model. While it works well for most people, it may fail miserably when a special case comes along. Salud Digna could be considered a fast-food-style laboratory, offering what most people need but no more.

So, if an unusual case comes along, Salud Digna cannot provide a specialist who, after many hours and much digging, might get to the bottom of the client’s complaint. After all, if you go to McDonald’s, they’ll fill your belly, but they are not going to cook you your grandma’s favorite recipe.

Some say Salud Digna is a laundering service for cartel money but, counters Vizcarra, “None of my business or social organizations have a financial relationship or dependency on any criminal organization. I always operate within the margins of the law.”

To end on a positive note, I should mention that in 2016, Salud Digna won Mexico’s National Quality Award for nonprofit organizations that have improved Mexicans’ quality of life. One such Mexican is Rosalía, a satisfied Salud Digna customer.

“People have no idea how much good this organization is doing,” she said. “Amoooo a Salud Digna [I loooove Salud Digna]. Thank God it exists.”

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for 31 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.