Vicente Fernández, a Grammy award-winning singer and actor known as “The King of Ranchera Music,” died in his home state of Jalisco on Sunday at the age of 81.

His family announced his death in a post on Fernández’s Instagram account, saying that he passed away at 6:15 a.m. on December 12, the feast day of another Mexican icon – the Virgin of Guadalupe.

“It was an honor and a great [source of] pride to share a great career with everyone and give everything for the audience. Thank you for continuing to applaud, thank you for continuing to sing,” the family said.

It didn’t give a cause of death but Fernández had been hospitalized since August after he suffered a fall at his Guadalajara ranch and required spinal surgery. The singer, who had suffered a range of health problems during the past 20 years including prostate and liver cancer, was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare autoimmune disease, while in the hospital.

The news of Fernández’s death triggered a great outpouring of emotion both in Mexico and beyond, especially in the United States where his music has long been loved by Mexican immigrants yearning for their homeland.

“I extend my condolences to the family, friends and millions of fans of Vicente Fernández, symbol of the ranchera songs of our times, known and recognized in Mexico and abroad,” President López Obrador said on social media.

Thousands of the singer’s fans flocked to the hospital where he died and his ranch to mourn, leave flowers and offer their condolences and encouragement to his family. A service attended by more than 10,000 people at which a coffin in which Fernández lay on display was held Sunday evening at an auditorium in Tlajomulco, located in the Guadalajara metropolitan area.

“I believe that the Virgin of Guadalupe took him on her day,” Virginia Calderón, a fan, told the newspaper El Universal after leaving flowers outside the hospital. “There will never be another voice like his.”

Born in 1940 in Huentitán El Alto, a town in the municipality of Guadalajara, Fernández spent most of his childhood on his father’s ranch on the outskirts of the Jalisco capital before moving with his family to Tijuana after their cattle business fell on hard times.

He worked in a range of menial jobs in the border city before returning to Guadalajara and singing for tips at the Plaza de los Mariachis, a square in the historic center with bars and restaurants where musicians perform.

“From the time I was young [I sang] but really my career started when I was 19 years old on a [television] show called La Calandria Musical in Guadalajara. After that I would go [and] sing at the Plaza of the Mariachis and would perform serenades for tips,” he said in a 2010 interview with San Antonio news outlet KENS 5.

In the early 1960s, Fernández moved to Mexico City, where he performed in a restaurant and sang at weddings. He met María del Refugio Abarca in the capital and the couple married in 1963 before having three sons and adopting a daughter.

After a series of rejections, Fernández finally got a recording deal and had his first hits in the second half of the 1960s with songs such as Perdóname, Cantina del Barrio and Tu Camino y el Mío, a ballad about unrequited love.

In 1972, he appeared in his first film – Tacos al carbón – in which he played the role of a street taco vendor whose life changed after he won a car.

Fernández would go on to appear in over 30 movies and record more than 100 albums that sold tens of millions of copies. His 1976 hit Volver, Volver cemented his status as the greatest ranchera singer of all time.

“When I started my career, I always had the confidence that I would one day make it, but I never imagined that I would reach the heights at which the public has placed me,” he said in the 2010 interview.

Among his most successful songs are El Rey, La Ley del Monte, Mujeres Divinas, Por Tu Maldito Amor, Las Llaves de mi Alma and Lástima que Seas Ajena.

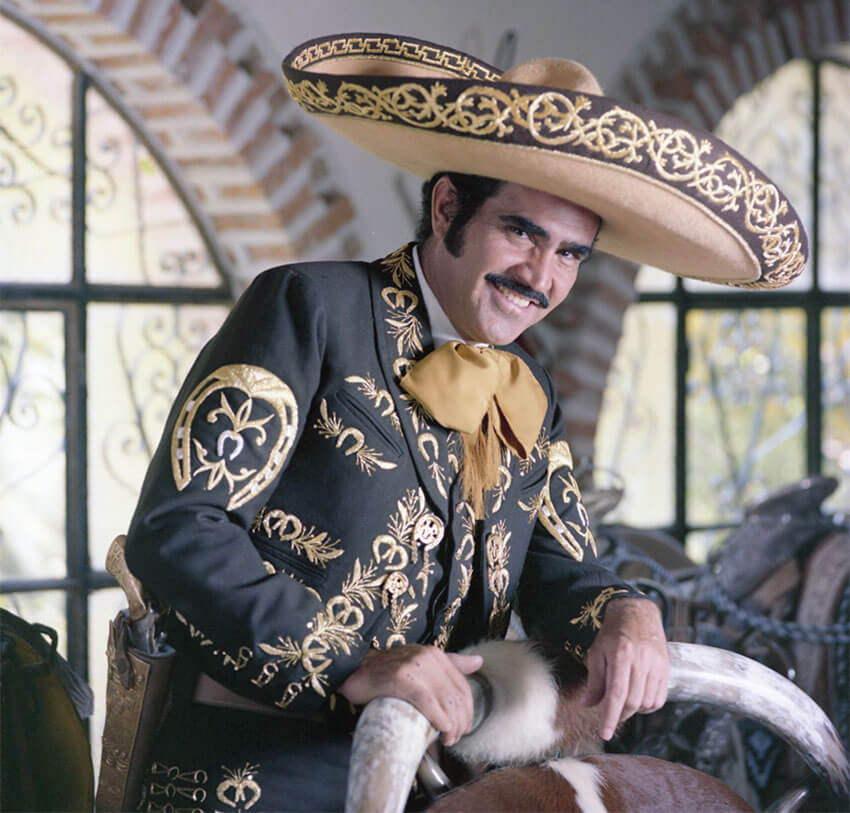

Also known as El Charro de Huentitán (The Cowboy from Huentitán) or simply Chente, Fernández won three Grammys and nine Latin Grammys as well as countless other awards and accolades including a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Known for marathon performances that he continued to give well into his 70s, “El Rey” of ranchera – a genre with deep connections to the values and traditions of rural Mexico – used to say he would continue singing as long as his audience wanted to listen to him. A swig of tequila often gave him a jolt of energy toward the end of long concerts.

The mustachioed singer invariably performed while dressed in an embroidered charro outfit and wearing his trademark sombrero. His performances in stadiums, concert halls, bullrings and cockfight pits, both in Mexico and abroad, were backed by full ensembles of mariachi musicians.

“Over a six-decade career, his voice became synonymous with Mexico itself,” National Public Radio national correspondent Adrian Florido wrote in an obituary.

“His velvety baritone was instantly recognizable, and his songs worked their way into the daily lives of Mexicans and lovers of Mexico the world over – the soundtrack to wedding parties and quinceañeras [15th birthday parties] baptisms, birthdays and funerals.”

However, his life wasn’t without controversy. In 2019, for example, Fernández was criticized after revealing that he refused a liver transplant out of fear the organ could have belonged to a gay person or drug addict.

Still, his legions of fans maintained their love for the “The King of Ranchera Music” until the very end.

Writing in the newspaper El País, DJ and music producer Camilo Lara described Fernández as a “badass charro” and “a kind of John Wayne of Jalisco.”

“… Chente had an extremely long career that turned him into the biggest mariachi superstar. Nobody knew how to connect with the Mexican migrants in the United States like him,” he wrote.

“… Chente didn’t stop singing until the applause ended. He was always very generous in his concerts. I don’t believe that his death means that the applause has ended. Perhaps he just withdrew to rest while he finishes another bottle of tequila.”

With reports from El Universal, El País and NPR