In May of 2019, the city of Ciudad Guzmán, Jalisco, announced the implementation of a radically new water and utility distribution system based on cutting-edge Dutch technology that would rid the municipality of its tinacos (water tanks on rooftops that provide potable water filled by private companies) as well as ugly telephone and electrical wires stretched above its streets.

Representatives of the Mexican and Dutch entities involved promised that, after only three years, members of every household in Ciudad Guzmán would be able to drink potable water from their kitchen taps.

Alas, the three years expired last month, and the tinacos are still there on every rooftop in Ciudad Guzmán.

Raul Mejorada of Guadalajara’s Grupo MGB Victoria — the hydraulic systems engineering company behind the plan to bring clean water to Ciudad Guzmán — is trying again. He announced this month that the Guadalajara is considering implementing the very same technology to transform the way water, electricity and other utilities reach consumers in Mexico’s second-largest city.

“But whatever happened to Ciudad Guzmán?” I asked Mejorada.

“The plan,” said the businessman, “depended on the state of Jalisco supplying 50% of the funding needed. They dropped out at the last minute, and everything fell through.”

Mejorada laid the blame squarely on how Mexico handles the taxes it collects. Businesses located in cities and towns pay taxes to the federal government. “But,” said Mejorada, “the federal government gives back only 18% of that money to the states, and a mere 4% to the municipalities.”

So Mexico’s municipalities are poor, and no one will lend them money. But Mejorada apparently learned from his experience with Ciudad Guzmán and worked with his Dutch colleagues at the KWR foundation — a unique fusion of Dutch companies and a water research institute — to come up with a solution to the financing problem.

Any city that wants this cutting-edge revamp of its water system must cede its utility-distribution rights to a fideicomiso (a trust). Members of the trust would include MGB Victoria and the KWR Foundation, but the fideocomisario (the trustee) is the municipality itself, which is also the trust’s beneficiary.

Guadalajara has already taken the step to create this fideicomiso for the proposed project, called the Sociedad Financiera Hídrica Mexicana. Why create a fideicomiso? Because the municipality is poor and can’t get credit, but the trust’s other members (MGB Victoria and the KWR Foundation) are wealthy and qualify for plenty of loans.

However, it must also be demonstrated to lenders that the transformation of a city’s utilities distribution system will be able to pay for itself. So Mejorada and his associates came up with a plan by which the new system is not only cost-effective but profitable as well.

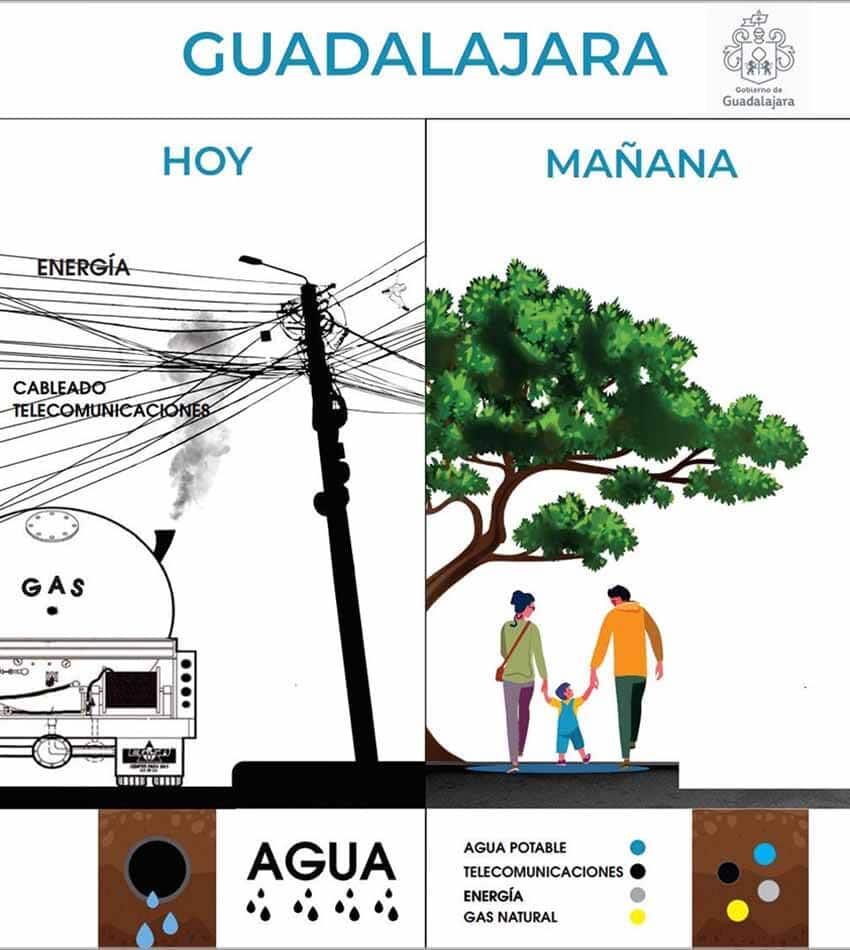

“To make the system profitable,” says Mejorada, “we add to the water distribution system other services that can generate money. So, alongside the pipe for potable water (which, by the way, is self-cleaning) we put a flexible tube carrying natural gas and a telecommunications tube for internet, cable and telephone — replacing airborne telephone wires, which are very expensive to install and maintain. We also supply a tube carrying electricity exactly the same way, underground, not through wires in the air.

“In this way, the setup becomes sumamente rentable [highly profitable]. Why? Because the utility companies that will benefit will all pay rent, and this will pay for the infrastructure.”

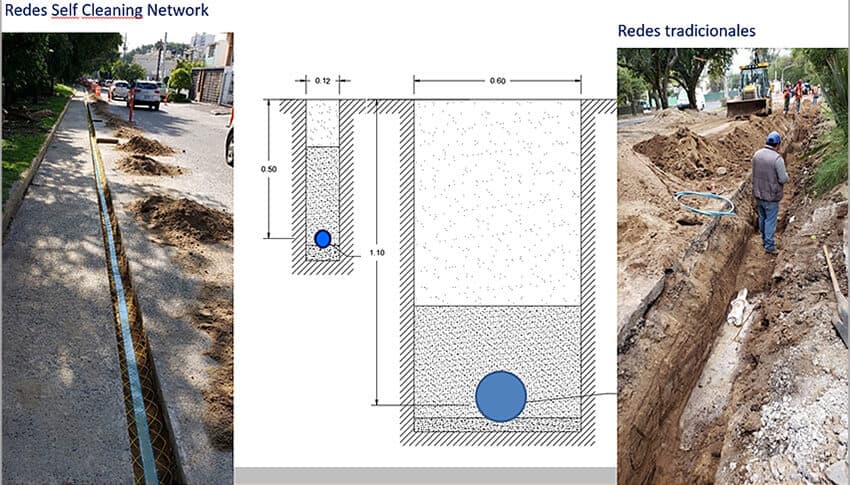

The new distribution system is entirely underground, using new, non-invasive tunneling techniques. And because none of the pipes — which are actually tough, flexible hoses — are more than four centimeters in diameter, the cost of installation is very low.

Mexico’s present water distribution system loses a full 50% of the water it attempts to carry. And it is for this reason that virtually all Mexicans drink bottled water, if they can afford it. This water-loss problem means that even though drinkable water is sent to Mexican homes (something required by federal law), by the time it gets there, it’s usually not safely drinkable anymore.

The problem is that when it goes through the normal water pipes, which lie right next to sewer pipes, the cracks in both end up mixing the two liquids, and what arrives at the customer’s house is now contaminated. The Dutch system uses super tough, flexible tubes, and the water pressure is on 24 hours per day. So the drinkable water goes from the plant to the home without contamination.

“We need to stop [this loss of water] with new technology,” says Mejorada, “and Holland has that technology in the form of small, open-ended distribution networks, which are different from any other country’s. Holland only loses 3% of its water.”

I asked Mejorada which neighborhood of Guadalajara will be the first to benefit from his project.

“The answer is easy,” he says. “We will start wherever it will be more profitable and easier to install. And because these are basic utilities, there will be more profit where there are more people.”

So they intend to focus first on areas where there are plenty of customers. “We will start in the poorest, most crowded parts of town,” Mejorada says.

A likely candidate for the first utilities revamp is Balcones de Oblatos, a colonia (neighborhood) at the east end of town overlooking the deep Santiago River Canyon, noted for having “lots of people and lots of potholes.”

The municipality of Guadalajara has already paid for a preliminary study, “and we expect that the process for approval will take about eight to 10 months. After that, the work will begin, and the first areas renovated will be generating funds for more and more sectors of the city.”

Mejorada claims that similar plans are underway in Zapopan and Chapala, where the village of Ajijic would be one of the first to experience the utilities upgrade.

Says Mejorada: “In my opinion, the chance that this project in Chapala will be in operation next year is 100%. We are talking about packages of 9,000 tomas, (connections or outlets), and Ajijic will need only 4,000, so we will be working in other areas along the lakeshore.”

“Once we start, we won’t be stopping because every time we connect a new customer, we are making money; the municipality is making money. So, one day, I hope to see Chapala free of overhead wires.”

Mejorada and his team went to great lengths to find a way to implement a badly needed project at the municipal level. Here is his final comment on the crusade he has been waging for years:

“The wealth of our country is generated in our municipalities, and the day we realize this, we will see a better, fairer and richer Mexico.”

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.