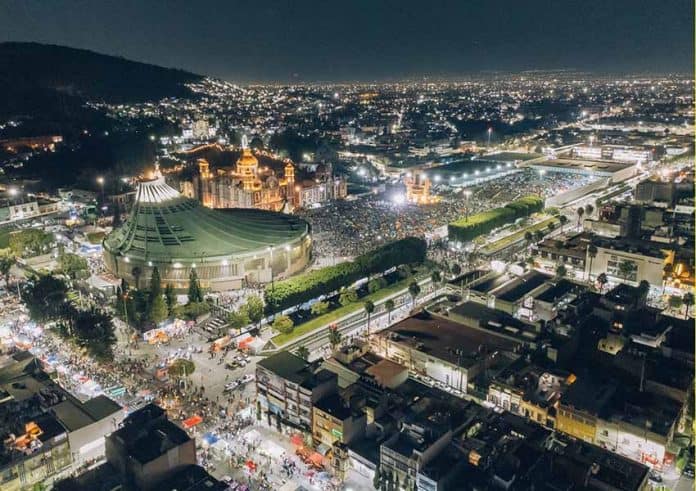

Mexico City officials said Monday that they’ve calculated that 11 million Catholic pilgrims arrived in the nation’s capital this year to converge at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Monday marked the culmination of pilgrimages by millions of Catholics from all over Mexico to the shrine to Guadalupe, an invocation of the Virgin Mary often credited with cementing Catholicism in indigenous Mexico. Pilgrims gather annually at her shrine for her feast day on Dec. 12.

City official Martí Batres announced that 11 million people had arrived at the La Villa Basilica complex in the days leading up to the Virgin’s feast day of Dec. 12.

It was not clear whether the number constituted an attendance record for visitors to the Catholic holy site for the Dec. 12 celebrations, but some sources have placed the record at 8 million visitors. The church’s rector recently said he expected turnout for the first restrictions-free celebration since 2020 to surpass previous attendance numbers.

Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum said that an estimated 5 million people arrived to the basilica on Sunday alone.

Typically, an estimated 95,000 Catholics per hour pass through the Basilica annually on the Dec. 12 feast day.

The city, which each year launches a massive logistics operation to support the influx, said it provided food and water to pilgrims at government attention centers along five routes into the city and provided medical attention to 2,721 people throughout the days of celebration.

Batres also said that the city had distributed 243,000 liters of water and that cleaning crews had collected 548 tonnes of associated trash since last week when pilgrims began arriving.

The faithful, a visible sight every year in the capital, come carrying bedding or tents on their backs to camp out in the basilica’s courtyard for days before in anticipation of the celebration. Many also bring family heirlooms — candles, statues, framed images of the Virgin, crosses and more to be blessed. Some faithful drop to their knees near the entrance and crawl in as a show of devotion or of thanks to the Virgin.

Many Mexicans who do not participate in the pilgrimage will still erect an altar to Guadalupe in their homes and celebrate on this day as well as in churches dedicated to her throughout Mexico.

But the basilica is special because Catholics believe that the Our Lady of Guadalupe first appeared at this site on December 9, 1531, to an indigenous Chichimec convert known as Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin.

The timing of this apparition of the Virgin Mary — who was dark-skinned and spoke in Nahuatl — came during the Spanish conquest’s earliest days in Mexico, only 10 years after the fall of Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan. At the time, inhabitants of the Valley of Mexico were still naturally skeptical of the religion their conquerors wanted them to adopt.

The story of the Virgin’s apparition to the indigenous Juan Diego is credited with having converted millions in Mexico to Catholicism.

According to Catholic lore, Juan Diego is said to have been walking past Tepeyac Hill on his way to religious instruction when the Virgin appeared, instructing him to tell the archbishop of Mexico City, Juan de Zumárraga, to erect a chapel in her honor.

But de Zumarrága was skeptical. Juan Diego returned to Tepeyac Hill later that day, when the Virgin is said to have appeared a second time. After Juan Diego informed her of his failure to convince the archbishop, she insisted that he return to de Zumárraga and repeat her request.

On Dec. 10, Juan Diego returned to the bishop, and this time, de Zumarrága asked for proof, so Juan Diego returned to Tepeyac Hill, where the Virgin appeared a third time, assuring him that she’d provide a sign the next day.

On Dec. 11, however, his beloved uncle became seriously ill and was near death, causing Juan Diego to miss his appointment with the Virgin. So on Dec. 12, when he went in search of a priest to hear his uncle’s final confession, he avoided Tepeyac Hill, ashamed that he had missed his appointment.

Nevertheless, the Virgin appeared, and when Juan Diego told her of his dying uncle, she responded, “Am I not here, I, who am your mother?” words that are engraved above the basilica’s entrance.

She told Juan Diego that his uncle was healed and instructed him to climb to the top of Tepeyac Hill, collect the flowers he’d find there — a miraculous sight in December — and bring them to the archbishop. He brought the roses he found to de Zumárraga, carrying them in his tilma, a traditional indigenous cloak. When he opened the tilma, it’s said the Virgin’s image revealed itself on the inside of the garment, which the archbishop immediately venerated.

In addition, Juan Diego’s fully recovered uncle told his nephew that the Virgin had also appeared to him, telling him to inform the archbishop of his miraculous recovery and that she wished to be known as “de Guadalupe.”

By December 26, the tilma was placed in a hastily erected chapel on Tepeyac Hill, of which Juan Diego became the caretaker until his death.

Pilgrimages to the small chapel began soon after it was built and have continued ever since. By 1709, crowds had so overwhelmed the site that a new shrine was built at the foot of Tepeyac Hill to house Juan Diego’s tilma for viewing, now located in the current basilica, built in 1976. The current basilica can hold 10,000.

For the millions of pilgrims at the basilica Monday, festivities began at the stroke of midnight, with those gathered outside singing “Las Mañanitas” (Mexico’s traditional birthday song) to the Virgin. The faithful then crowd the basilica’s entrance to view the cloak inside and have objects blessed.

The area around the basilica is typically filled with vendors of all kinds — selling food as well as religious souvenirs. People come in religious costumes, and there is singing, dancing, prayer and performances of traditional indigenous dances.

In 2002, Pope John Paul II traveled to Mexico to canonize Juan Diego as a Roman Catholic saint, the first indigenous to the Americas. Guadalupe has long been the patron saint of Mexico and was declared by the Church the Patroness of the Americas in 1945.

Juan Diego was also made a saint in 2002, the first saint indigenous to the Americas, with a feast day of Dec. 9. Pope John Paul II, who canonized him, traveled to Mexico for the ceremony.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán last year and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.