How a river could be both heavenly and hellish at the same time is hard to imagine, but such is the state of Mexico’s Río Santiago these days.

The river flows out of Lake Chapala, makes its way to Guadalajara — where it nearly encircles the city — and then works its way through a string of dams before finally spilling into the Pacific in Nayarit.

Horrible pollution of the Santiago near Guadalajara by some 600 factories, along with raw sewage from thousands of homes, seem to be responsible for widespread cancer and kidney failure among those who live on the river’s shores and breathe its noxious vapors.

Outrage at this state of affairs has provoked an unusual proposal by some of Mexico’s economists — with worldwide backing.

It’s called “shame economics” and proposes to impose a kind of duty or tax on all the factories near the river, based on the net worth of each, without assigning blame to anyone.

“Find a solution,” say the economists, “or the duty will go up.”

The amount of the fine would reflect the cost of health care for the afflicted and also the loss of income, water sports and tourism along a once magnificent river that no one can approach because of the stench.

The Santiago River’s untouchable beauty is immediately apparent to those few people who have walked its tree-lined shores at the foot of the magnificent canyon that forms the northern boundary of greater Guadalajara. Visually speaking, the rocky river bed, backed by sheer red cliffs 500 meters high, is picture-postcard perfect.

But postcards have no smell.

What is the city of Guadalajara losing because of this situation?

San Antonio, Texas, has shown the world how to turn a pretty river into fame and fortune. The city’s celebrated River Walk — billed as “The Number One Attraction in Texas” — brings in over 11 million visitors per year that are delighted to sip coffee at quaint cafés as they watch the river flow.

Imagination and good taste has turned the River Walk into a successful attraction, but the Santiago, as it flows along the northeast corner of Guadalajara, has a natural beauty that far surpasses anything that the San Antonio River has to offer.

As you walk downstream along the riverbank, watching the water swirl and eddy through great moss-covered rocks shaded by tall, lovely trees, you gaze in awe at a towering red canyon wall on your right, while hot springs cascade down the gentle slope on your left. Here we have all the ingredients for a combination River Walk and spa that any city in Europe would long ago have transformed into a first-class tourist attraction.

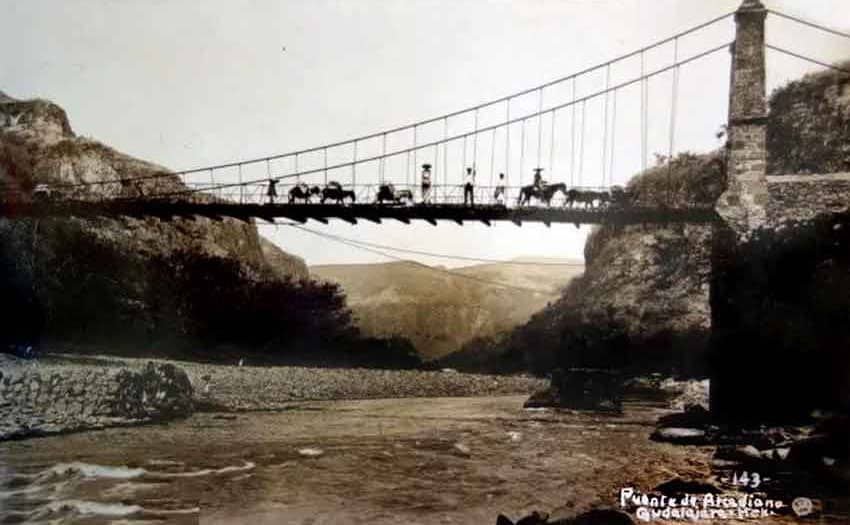

Then, 8 km downstream, we come to the beautiful little Puente de Arcediano, which crosses the river.

Constructed in 1894, this was only the third suspension bridge to be built on the entire American continent, a testimony to the importance of this section of the Santiago before pollution turned it into a sewer.

This area around the bridge was bustling with activity in Guadalajara’s early days. Near here were located haciendas surrounded by fertile fields and orchards that took advantage of the semitropical climate at the bottom of the canyon, supplying Guadalajara with mangoes, papayas, sugarcane, oranges and caracolillo (peaberry) coffee beans.

This was also the spot where donkey caravans crossed the river, transporting goods between Guadalajara and Zacatecas.

And 43 km km northwest of the Arcediano Bridge lies the Santa Rosa Dam, which has created a gorgeous lake on the Santiago with a sharply rising carpet of green topped by the 500-meter-high red canyon wall on one side. On the opposite shore, there’s a veritable sea of blue agaves stretching as far as the eye can see.

But this fairytale lake is dead quiet: no lakeside cabins, no fishermen, no water skiers, no laughter. No, this lake of unspeakable beauty is also a cesspool of unspeakable odors and poisons.

How much money is lost to Guadalajara because an idyllic lake located only an hour’s drive from the city’s Ring Road is unusable? The amount needs to be calculated and added to the shame economics duty imposed on the Santiago’s polluters.

From the Santa Rosa Canyon, the river flows into the state of Nayarit and somewhere along the way, a miracle occurs: the river actually manages to cure itself!

Years ago, I stumbled upon a pueblito in that part of Nayarit called Las Cuevas. As I drove down its few streets, I saw a boat in front of every home. Because the only stream I knew of in the area was very shallow, I couldn’t imagine what the boats were for.

Finally I asked a local man.

“Well, here at Las Cuevas, we are blessed with something not every village can enjoy,” he told me. “You can’t see it from here, but at the bottom of the canyon behind our village lies the Santiago River, right before it enters the Aguamilpa Dam. Our favorite pastime is to go boating there — and, of course, catch fish.”

“What? You actually eat fish from the Santiago River? “

“Yes, the dam is full of lobinos (bass), really big ones, and they’re really tasty!.”

I wondered whether 300 km of winding river could remove the coliforms, chemicals and heavy metals that contaminate the river upstream. So I consulted Dr. José de Anda, who specializes in natural ways to purify sewage.

He told me that at this distance, the waters of the Santiago show no influence from the pollution in the Guadalajara area. “But they still suffer from local contamination. The worst thing we found in these waters were parasites. So, as long as you fry or cook these fish, you can eat them.”

The river finally ends its long journey from Lake Chapala to the sea 20 km north of San Blas in Nayarit.

Will these economists’ shame economics idea succeed in restoring the entire Río Grande de Santiago to its former splendor?

If we all pull together, it just might happen.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.