Though it’s been a while since I’ve taught a class, the memories I have of being a high school social sciences teacher from 2006–2011 in Querétaro remain sharp — it was truly a unique experience.

Most of my students were the sons and daughters of the city’s elite. At the time I was there, we had several state politicians’ kids and many children from the region’s prominent business owners. Monthly tuition for each child was just over half of my monthly salary, and a peek outside the parking lot during the school day would reveal a cadre of bodyguards waiting to escort the ones from especially wealthy families to their homes.

I taught high school kids. High school kids are kind of high school kids everywhere: some are lovely, some are entitled and/or defiant jerks, some are just plain weird. Most, honestly, were pretty nice and well-mannered, especially if you consider what a self-centered period of life teenagerhood is.

I told myself that my work mattered greatly, as I was getting a small and unique chance to educate, quite literally, many of the future leaders of the city, state and possibly even the country.

And, boy, did I try hard.

Though I haven’t had a front-row seat to the culture wars in my own country, I’m pretty sure I’m exactly the kind of liberal teacher that conservative parents and local politicians would have wanted immediately fired and possibly burned at the stake.

Because look: if I’d been able to turn those kids into vegan socialists, you’d better believe I would have. I was not successful, but it certainly wasn’t for lack of trying!

Alas, most of them today (many are my Facebook friends!) are now simply 30-something rich people, the status-quo capitalism of Mexico having given them very little personal reason to “fight the system.” For the majority of them, “the system” is going just swimmingly.

They may sympathize with the masses, but I don’t see any of them fighting to cut their own privileges in order to even things out.

For most schoolchildren in Mexico, things are, and will likely remain, quite different.

This is true particularly for those younger students who attend public school and will be the recipients of the SEP’s new and (apparently) controversial textbooks.

I’ve been following this upset online, if you can count reading a couple of articles and looking at related memes as “following.” I’ve also virtually paged through some of the books that my daughter will receive this coming year, since we’re not in one of the states where the governor has declared they’d refuse to distribute them.

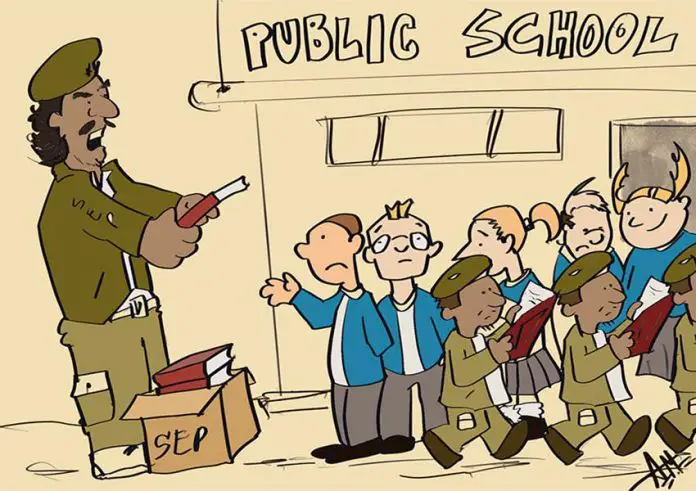

To me, the books seem just fine (you can look at the PDF versions here). I keep hearing about myriad errors in them, but in my own browsing, I haven’t yet come across any. Another complaint (possibly — just maybe — slightly exaggerated) is that the books are teaching “communist” values: have a look on Facebook, and you’ll find meme after meme joking and implying that after reading them, kids will be walking around in red sweaters with their own scythes and Che Guevara berets, fist-pumping solidarity gestures at each other in the hallways.

Ha! I wish.

Really, though, that’s not how it works.

For those not in the business of trying to “indoctrinate” (i.e., teach) kids, let me tell you: it’s harder than it looks. Again, I myself went all out, but there’s nary an anti-capitalism meme to be found among my former students’ social media pages. Nope. They’re filled with pictures of luxury world travel and evening gowns.

Conclusion? People vastly overestimate the degree to which students actually pay attention to their textbooks, let alone their teachers.

People who want to sound serious in their critiques have mostly stuck to talking about the books’ typos. But I don’t think the outrage is really about a few punctuation errors.

If there are schools that don’t even have toilet paper or soap in the bathroom, and others that are frequently left without water and electricity, outrage about a misplaced comma seems, well, misplaced.

So, what are they afraid of?

Here’s my radical take: they’re not worried about students like the ones I had. They’re worried about the future low-wage workers of Mexico developing a real life Marxian “class consciousness.” Because if that happened, they might stop accepting the social and economic status quo. They want to avoid class warfare, in which they’re not guaranteed to be on the winning side.

Sending one’s children to school is a compromise: you have to relinquish some of your own control in exchange for getting some time to yourself (usually just to work, not necessarily for fun stuff).

If you’re afraid of what they’re learning in school and you prefer that economically disadvantaged students have no textbooks of any kind — rather than allowing them to read what’s inside ones you consider flawed — then it’s time to examine what your real fears are.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.