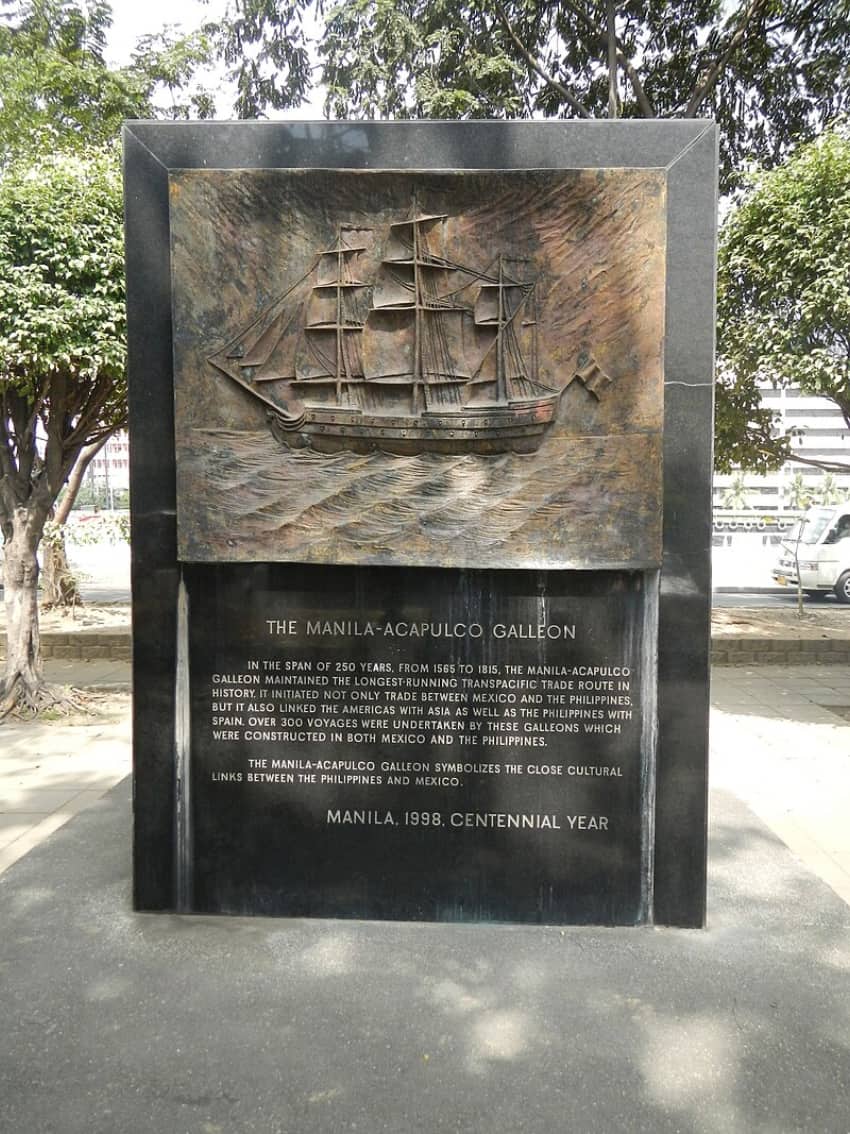

In the 16th Century, the Manila galleon was a fleet of Spanish merchant ships that made the perilous trip along the trade route between the Philippines and Acapulco, which was the only port authorized by the Spanish to handle the Manila trade. At the time, Manila was under Spanish rule and was the wealthiest and most strategic port in the world, connecting trade between East and West.

Spain was able to maintain the Manila galleon trade route for 250 years. It finally ended in 1815 during the Mexican War of Independence. One historian notes, “the Manila galleon was one of the most persistent, perilous and profitable commercial enterprises in European colonial history.” In addition to bringing Spain the wealth of Asia, the Manila galleon introduced new exotic spices to Mexico that are now prevalent in cuisine throughout the country, including cumin, and cinnamon.

In the late 1500s, the rivalry between Spain and England was at its peak and piracy between the two empires became commonplace. To destabilize Spanish power in the Americas, Queen Elizabeth I gave her English privateers — essentially authorized pirates — permission to attack Spanish merchant ships. Some of England’s most famous privateers, including Walter Raleigh and Francis Drake, were active during Elizabeth’s time.

According to historian Peter Gerhard, author of “Pirates of the Pacific, 1575-1742″: “piracy in the Pacific was undertaken only by the hardiest of pirates.” “If caught,” Gerhard writes, “they were dealt with quite harshly for the Spanish looked upon them as unprincipled thieves and scoundrels.” English pirates captured by Spain could be sentenced to death or turned over to the Mexican Inquisition.

Although piracy was quite common at the time in the Caribbean, it was not as prevalent on the Pacific coast of South or Central America. As a result, Gerhard writes, Spanish possessions on the Pacific were not as heavily fortified. For pirates, this was an opportunity — a dangerous one. In a time before the Panama Canal, getting to the Pacific coast of Mexico or South America meant crossing “the jungles of Central America or [making] the long and dangerous trip through the Strait of Magellan or around Cape Horn.”

The privateer Sir Francis Drake was the first. On his 1577 raiding voyage — during which he became the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe — Drake’s crew raided and pillaged Spanish settlements and ships up and down the Pacific coast of the Americas.

Nine years later, 27-year-old privateer Thomas Cavendish, known in history as The Navigator, decided to follow in Drake’s footsteps. He became the most famous pirate of the Pacific.

In July 1586, Cavendish sailed from Portsmouth, England with a crew of 123 and three ships. After sailing through the Strait of Magellan, they reached the Pacific in February 1587 and proceeded to loot villages and capture Spanish ships as they sailed up the coast to Mexico.

In October, Cavendish reached Mazatlán and dropped anchor just off Deer Island. After repairing their ships and taking on supplies, they sank the supply ship and headed for Cabo San Lucas to lie in wait for the next Manila galleon.

The Santa Ana was a large ship weighing over 600 tons manned by 100 sailors and carrying passengers, including women, under the command of Captain Tomás de Alzola.

On November 4, the Spanish ship Santa Ana slowly sailed along the coast of Baja California under brilliant blue skies and favorable winds. She had left Manila four months earlier laden with Oriental treasure: gold, pearls, and silk from China; ginger, cloves and cinnamon from the Spice Islands; rare jewels from Burma; and ivory from India. The Bishop of the Philippines described her as “the richest ship to ever leave these isles.”

On the 14th of November, as the overloaded ship passed Cabo San Lucas, the lookouts sighted sails in the distance. Captain Tomás de Alzola reduced the sails and ordered camouflage netting to be hung. Weapons were issued to the 160 passengers and crew. Despite carrying such valuable cargo, the Santa Ana had no cannons on board: on a previous trip, the cannons were left behind to protect the port of Acapulco.

Fierce hand-to-hand combat erupted when sailors from the Desire attempted to board the Santa Ana. Their first attempt was unsuccessful. At least two seamen and the captain of the Santa Ana chronicled the battle that ensued.

Spotting the Santa Ana, the Desire and Content gave chase, catching up with the larger vessel in about 4 hours. At 600 tons, the Santa Ana, was a veritable fortress but was so heavily laden with treasure that it could not maneuver and had no cannons to fight back.

After several hours of battle, the Santa Ana started to sink and finally struck her colors and surrendered. Captain Alzola chronicled that “on the third day, the seventeenth of November, they [Spanish crewmen] went to the Port of San Lucas under threat of death.”

Once the British Desire and Content were laden with as much booty as they were able to carry, they set off separately for England. The richly laden Content was never heard from again.

Thomas Cavendish returned to England in 1588 a wealthy man and a hero. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth I on the deck of the Desire. He set out again for a second raid of the Pacific coast but never made it, dying at sea at the age of 31. Tales of his exploits, however, spread to pirates worldwide and increased the number of privateers who pursued riches on the Pacific coast of the Americas.

The captain and crew of the Santa Ana who were abandoned at Cabo San Lucas were able to repair the ship well enough that they made it to the Mexican mainland and eventually south to Acapulco. It was the largest loss suffered by a Spanish galleon in the 250-year history of Acapulco-Manila trade.

The fate of the Content and the treasure it carried remains shrouded in mystery. However, the dream of its pirate treasure has endured through the ages. Legends of the ship have been passed down through the Indigenous peoples of Baja California.

One legend refers to a wooden ship found stranded in a bay with the dried-up corpses of men on board. Natives purportedly built a fire on the ship’s deck, inadvertently setting fire to and sinking the entire ship. Another legend places the Content in a sheltered bay on the Pacific north of Cabo San Lucas, but 400 years of storms and tides would have buried any evidence.

The rich treasure of the Content allegedly consisted of millions of silver pesos in addition to the plunder from the Santa Ana. While many have searched for it over the years, the peninsula has not yet yielded the ship’s location.

Many people believe that the treasure of the Santa Ana is still out there.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive, researcher, writer, and editor. She has been writing professionally for 35 years. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing. She can be reached at AuthorSherylLosser@gmail.