We Mexicans love giving things and people fun nicknames. And few things get as many nicknames in Mexico as stereotypes of other Mexicans.

Living abroad, I’ve come to understand that as much as we dislike stereotypes, they tell us a lot about the society we live in. And Mexican stereotypes are no exception. Understanding them gives foreigners valuable information, not only about the complex world of classism in Mexico but also about Mexican politics, religion and even workplace dynamics.

They’re also a great window into Mexican humor, because as you’ll see, they are a major source of satire.

The following are the most common stereotypes you’re likely to come across on social media, in casual conversations between Mexicans, or even in statements from President Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

But the most important question: Which one are you?

Godinez

Do you work in an office? Do you bring food to your job in Tupperware? Do you work a 9 to 5? Then you are a godinez. And if you wear an office badge, you’re in the top ranks.

Before working from home became a thing, I was once a godinez, too. I used to arrive at the office by 9 a.m., wear formal attire, store my food in the office fridge and have a drawer full of snacks (yes, that included chips and salsa Valentina).

In the morning, my work friends and I would prepare coffee in the kitchen and have our usual dose of I-hate-my-godinez-life conversation before diving right into work, just as any responsible godinez would do.

When I couldn’t make it home for the two hour lunch break, I would eat from my Tupperware or have lunch with my other godinez colleagues at the same old restaurant around the corner.

As any godinez, the quincenas (paycheck day every fortnight) were my favorite days of the month and “ya depositaron” (they’ve paid) my favorite words.

Despite every Mexican knowing what a godinez is (besides a surname) it’s still unclear why we chose this name. What we know is that godinez is not derogatory and is always a great way to add humor to any conversation.

Some examples of godinez in TV shows are Hugo Sánchez from “Club de Cuervos” and Betty in “Betty La Fea” (the original, Spanish language version of Ugly Betty).

Mirreyes

This stereotype only applies to men. But if you’re a woman, read on to find out if your man is a mirrey.

Mirrey is a combination of two words: “mi” which means “my,” and “rey” which means “king.” So, it literally means My King. The term originated as a greeting among the elite young male descendants of Lebanese immigrants in Mexico, spreading across the country through social media in 2010.

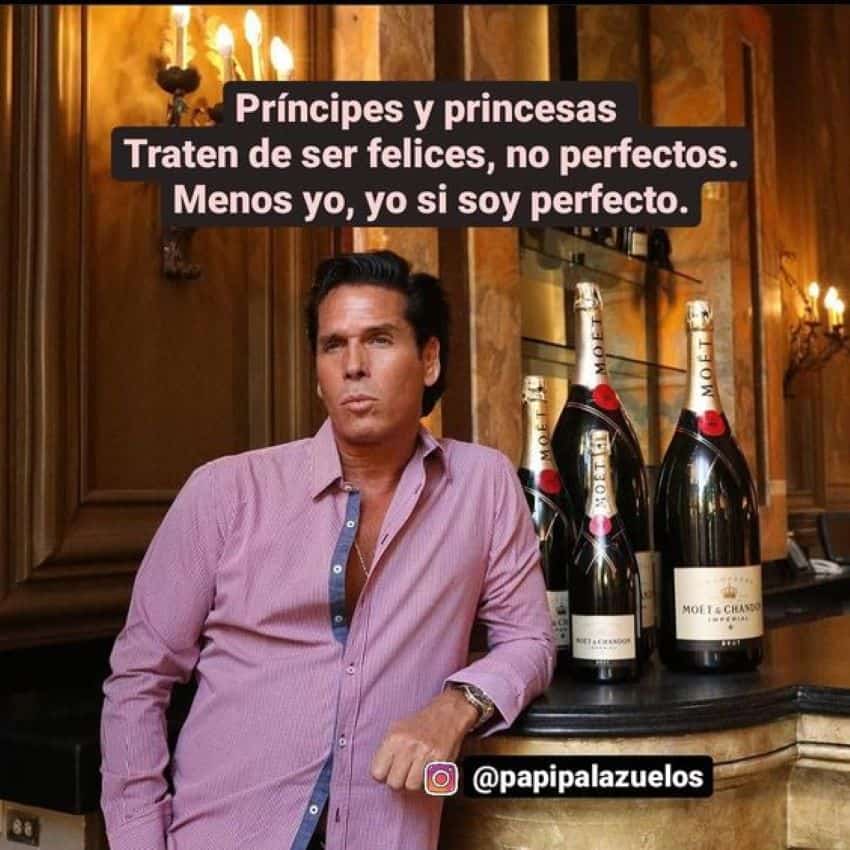

It describes a distinct stereotype within the whitexican and fresa realm: rich guys who lead an ostentatious and arrogant life. They wear shirts unbuttoned halfway down. Expensive loafers, lotions and watches. They are typically tanned. Some even call themselves entrepreneurs, making and breaking businesses sponsored by their family’s wealth.

They also use a specific lexicon, calling themselves papá (dad), lord or príncipe (prince) and using suffixes like “uki” and “irri” – they don’t go to Acapulco, they go to “Acapulquirri.” They don’t date girls, they date “lobukis” (chicks/babes).

Actor and businessman Roberto Palazuelos is constantly the object of memes representing mirreyes. Another particuarly notable example is Mexican singer Luis Miguel.

The term mirrey is usually inoffensive because many mirreyes take pride in being one.

Fifís

Fifís is a term that we’ve used in the Hispanic world for years to refer to refined people in high-class society. It is even in the dictionary. The Real Academia Española (RAE), the equivalent of the Oxford dictionary in the Spanish speaking world, defines a fifí as “a pretentious person interested in being fashionable”.

In Mexico, the term was never political and wasn’t used as an insult. But then López Obrador happened.

President López Obrador began to use the term during his 2018 presidential campaign, to refer to the opposition. He has also used it to accuse the press of being fifí. However, in a morning press conference in July 2022, he changed criteria and narrowed the requirements to be a fifí, arguing that “there are levels of fifís.”

According to him now, to be a fifí one must:

1) Own an airplane.

2) Own a yacht.

3) Live in the Mexico City neighborhoods of Las Lomas, Santa Fe “but in La Toscana,” or El Pedregal. He remarked that living in Del Valle (a middle-class neighborhood), “is not enough” to be a fifí.

López Obrador has also associated fifí with negative traits like selfishness, materialism, unscrupulousness and superfluity, adding that “one must look to improve oneself, but never aspire to be a fifí.”

Calling someone fifí is offensive. However, we have found ways to satirize it.

Dale RT a este AMLO para que tengas un día #fifí 😎 pic.twitter.com/DxQF5nX1RR

— Nación321 (@Nacion321) August 10, 2018

Now, if fifí defines the opposition of López Obrador, what term is used for his supporters?

Chairos

Chairo has various meanings across the Hispanic world and four meanings in Mexico alone. One of those meanings (someone who supports socialist causes) has developed into a pejorative noun to describe people who passionately adhere to ideology but lack real commitment to action.

Since the presidential campaign in 2018, the term has increased in popularity as a pejorative noun for the president’s followers, who largely tend to be low-income and darker-skinned. As such, chairo may have class and racial connotations, too.

Chairo and fifís are antagonists, frequently appearing on ‘X,’ in political conversations among Mexicans and in López Obrador’s speeches.

Earlier this month, López Obrador said that he is a “chairo” president and remarked that he is not a “fifi.” However, he added that he “respects fifís.”

Whether the term is offensive depends on whether you are a proud supporter of López Obrador.

Gabriela Solis is a Mexican lawyer turned full-time writer. She was born and raised in Guadalajara and covers business, culture, lifestyle and travel for Mexico News Daily. You can follow her lifestyle blog Dunas y Palmeras.