The time had come: I finally had all my paperwork to finalize the divorce I’d been trying to get for 3 years. Mexican bureaucracy, among other things, had meant it had taken so much longer than I ever thought it would, and COVID-19 hadn’t helped.

But as I stood in the divorce office of the Registro Civil, I sobbed, practically soaking the desk. To anyone walking by, it must have looked like that final step had devastated me.

I wish that had been the reason for my tears. Alas, the cause was far more predictable: I didn’t have all the paperwork I needed.

I’d done everything I could to prepare. I’d checked online. I talked to the second-to-last-person in the office downstairs to ensure I had everything. I had the official sign-off from the judge, and copies of the official sign-off from the judge. I had a good lawyer friend look over everything. I was so sure that I was set!

But when the lady at the Divorce desk let out a sigh and a drawn-out “híjole.” — an adultier version of “uh-oh,” but with more regret and weariness — I knew my journey was far from over.

And I was right.

You only think you’re close

When I had my civil ceremony at that same civil registrar’s office, the rules hadn’t been that stringent. “You can just translate your own birth certificate, it’s fine,” they’d told me. By comparison, getting married was a little too easy.

So what was I missing? Have you been on the edge of your seat? It turns out that, as a foreigner, I needed to have my birth certificate. And not just a copy of my birth certificate, lest you think “Oh, that’s all?”

No, I needed my birth certificate both apostilled and translated by a perito traductor: a Mexican certified translator.

An apostille? As in it needs to be notarized?

Oh, no, my friends. Not like a notarized document. A notarized document is child’s play. Notarizations, at least in the US, are simply to confirm that signatures on documents are valid. Notably, notaries in Mexico do much more than that. They also draw up legal contracts and documents. They are also notably more expensive. But that’s a topic for another article!

An apostille is a certification that validates public documents — such as birth and death certificates, marriage licenses and the like — for use in countries that are party to the 1961 Hague Convention. The document, of course, must be an officially certified document and not simply a copy.

In the United States, the certificate is created by your state’s Secretary or Department of State. In Canada, either Provincial authorities or Global Affairs Canada can help you.

What you must remember is this: they can only be obtained in your own country.

Apostille everything you can, and notarize the rest

As you might have guessed by now, the easiest route is to get all this done well before you come to Mexico. If you’re planning on doing it by mail — even if you’re ordering online — leave several months for everything to get back to you just in case. But if you’re not too far away, I’d advise just showing up at the appropriate office to get it done that day.

What should all this include?

Birth certificates

Mexican authorities seem to ask for one’s birth certificate for everything. There’s nothing to gain in asking why — I often have to suppress my snarky “Proof of birth? I’m sitting here, aren’t I?” comment. Just know that they’ll need it.

If your name is different from your birth certificate — perhaps you changed it when you got married — you’ll need that to be as legally clear as can be, as well. In Mexico it’s not common for people to change their names, so you’ll need to be prepared to explain and show how that legally happened.

Death and divorce certificates

If you think there’s even a one-in-a-million chance that you might get married again, get these. You might want them anyway for questions of property and such as well, though that’s an area that I admittedly don’t have experience in.

Anything having to do with your kids

Custody papers, court orders, whatever: you’ll need them, especially if you’re a single parent with custody of your children. A friend of mine recently went through a nightmare when she tried leaving a vacation in Colombia with her son. Even though she had primary custody and a restraining order against her Colombian ex, the authorities would not let him leave until she procured the appropriate documents from the U.S. It took her two solo international flights and thousands of dollars to sort it out. Mexico is not Colombia, of course, but it’s certainly not something I’d risk!

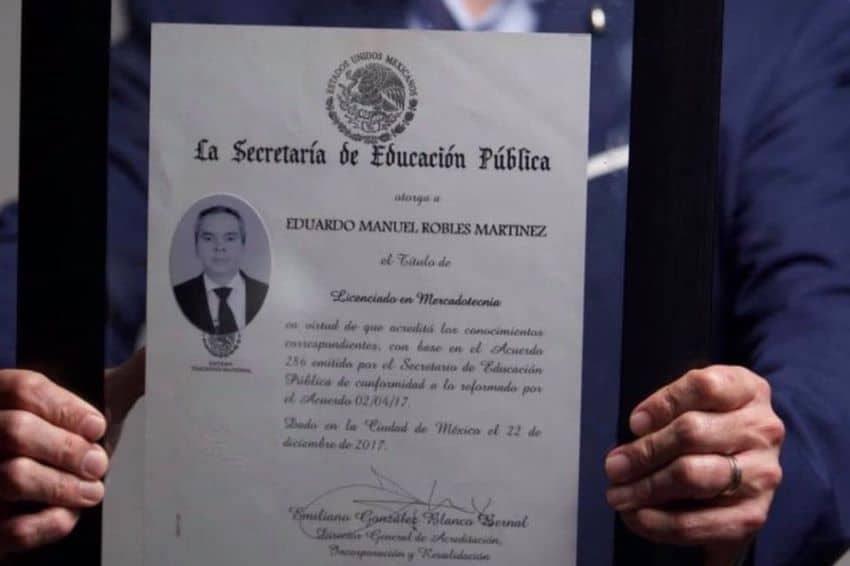

Diplomas, transcripts, school records

If you want to go back to school at any point in Mexico, you’re going to need proof of your schooling in your country. Applying for a local job might warrant some official documentation for these things, as well. Likewise if you want to send your children to school!

Deeds and titles to property

Though it may be hard to imagine for what you might need these in Mexico, it’s simply a good idea to keep them around. You never know!

If you can’t apostille something, get it notarized

Not everything is apostille-able. While I can’t give you a complete list myself, I would encourage you to check with your local authorities and go ahead and get everything apostilled you’re able to.

For things that don’t qualify, go to a notary in your country, which is essentially the next best thing. When it comes to immigration, for example, you’ll likely need to show proof of income through banking statements. I personally was never asked for notarized versions of these, but it’s been a while. I wasn’t asked for an apostilled and translated birth certificate when I got married, either. Things change.

Better safe than sorry! For translations, just wait until you get here; the appropriate authorities will tell you if you need them or not, and if they must be done by a perito traductor.

So what happened with my birth certificate? Luck and generous family members, that’s what. Luck: my dad still lives in the city where I was born, and so does my sister. First, my dad went to the public records office, got a certified copy of my birth certificate, and mailed it to my sister. From there, my sister drove two and a half hours to the Secretary of State’s office in the state capital. She got it apostilled that day and FedExed it to me. I went to have it translated, and headed to the civil registrar’s office the next day.

That time, the only tears I was crying were tears of relief.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sarahedevries.substack.com.