Feb. 11 is the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, the perfect opportunity to look back at the career of a most remarkable Mexican woman Ynés Enriquetta Julietta Mexía.

Mexía was born in May 1870, in Washington D.C. where her father, Enrique Mexia, was a diplomat. They were a wealthy family of some fame; a grandfather had been a general executed after picking the wrong side in one of Mexico’s numerous revolutions. Neither fame nor money are guarantees of a happy life, however, and her parents divorced while Mexía was still a toddler. Her childhood was spent living with her mother in Texas, but as a teenager she joined her father in Mexico. Little is recorded from this period of her life, but in 1897, at the age of 27, she married a Spanish-German merchant, Herman de Laue.

The first indication of Mexía’s drive and organizational skills reveal themselves when she inherited land from her father and opened a pet and poultry stock raising business. The next years were traumatic. Her husband died and she married Augustin Reygados, a man who worked for her and was considerably younger. It did not prove to be a wise choice, for Reygados drove the business into bankruptcy. With her life crumbling, Mexía suffered a mental breakdown and left Mexico to seek medical care in San Francisco. At this point, Ynés Enriquetta Julietta Mexía was a middle-aged widow, separated from her second husband, and struggling with mental health problems. It was at this low point that she found a new purpose in life.

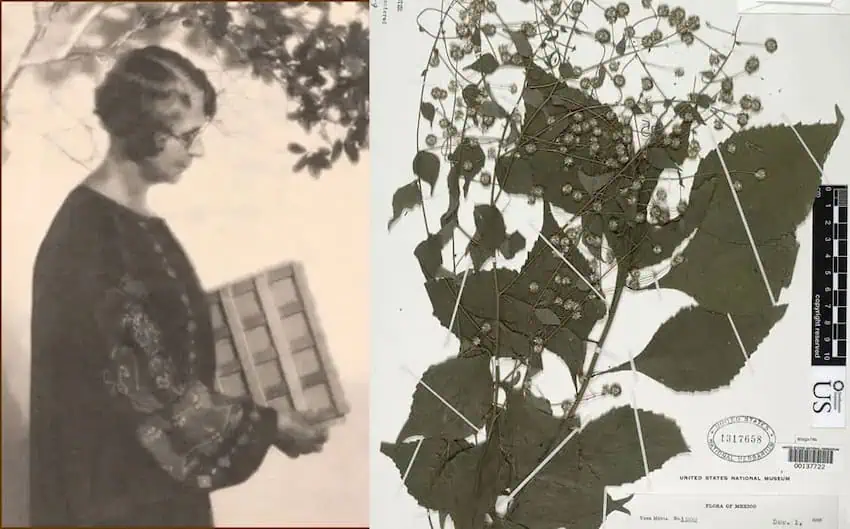

Part of Mexia’s recovery involved filing for divorce, while another factor was joining local hiking clubs. It was on long walks into the mountains that she discovered a passion for plants. Mexía still had the advantage of family money and enrolled in a natural science course at the University of California Berkeley. There she caught the eye of Roxanna Ferris, a recognized expert on the plants of California and Mexico. Ynés was invited to join an expedition that would explore remote regions of Mexico. It is uncertain why she was chosen, but being a Spanish speaker with Mexican nationality may have played a role. Despite the trip ending early when Ynés took a bad fall that required medical attention, the expedition yielded 500 botanical specimens, including several new species, one of which was given the name Mimosa mexiae. Mimosa are a remarkable family of plants with leaves that contract when touched and the new mexiae addition to the family produced a gorgeous purple flower. This was the first of around fifty new species that would be named in Mexia’s honour.

For the rest of her life, Mexía traveled from the northern regions of Alaska to the southern tip of Tierra del Fuego. Though she had a short professional career — only 13 years — she collected a large number of specimens, 145,000 according to the British Natural History Museum, 500 of which were new species. Some of these trips were of considerable length. Her exploration of the Amazon stretched from November 1929 to February 1932 and involved floating down the Amazon on a raft and flying over the Andes in an airplane. An article in the San Francisco Examiner entitled “She Laughs at Jungle Perils” tells of Ynés eating a poisonous berry and then sticking a chicken feather down her throat to make herself sick.

The reward of the Amazon expedition with all its adventures was 60,000 specimens. We need to step back a moment here to think what this means. To stand in the middle of an area of dense forest and to recognise what is of interest — perhaps a different variant of a common plant, or some small scrub that might never previously been recognized — demands a combination of knowledge and instinct.

Mexía was meticulous in her documentation of the samples she collected, this helped by considerable skill as a photographer. Yet, she was not the complete scientist. She did not study for her PhD, and it was collecting that fascinated her, leaving the follow up work to others. She did not shy from the public spotlight and her lectures such as “Furthest South America,” presented to the University of California, have been described as ´vivid and enlightening´. It was also a reflection on the esteem in which she was held. She was usually the only speaker at such events without the title ‘doctor’ in front of their names.

While we have a detailed log of her expeditions, Ynés Mexia’s personality remains more difficult to decipher. She did not seem to endear herself to people and has been described as spoiled, egoistical, quick tempered and argumentative, yet the evidence for this is poorly documented. The California Academy of Sciences website even claims that she stabbed a UC Berkeley graduate student in the leg after the student teased her while having lunch. Again, there are no details, but as it was over lunch, and there were no criminal charges, it was probably a stab with a piece of cutlery.

Her second marriage to a younger man might demonstrate a moment of infatuation and passion that was a marked deviation from her usual behaviour. It is notable that there is no mention of any romantic attachments after the second divorce. It was not only in her private life that Mexía enjoyed her own company. From very early in her collecting career she preferred to work alone and although her eye for interesting specimens gained her invitations to join expeditions, she seldom seemed to be invited a second time. Her expedition to Ecuador is well documented and offers clues to a side of her nature that could have made her difficult to work with. This trip was in search of her personal Holy Grail of plants, a wax palm that had been described by explorers but never cataloged by scientists. It was a wet, cold trek into one of the most remote places on earth and the way she drove her team of local guides was forceful to the point of fanatical. At one point, when her local guides refused to move, she left them. Whether she was confident they would follow, or just indifferent, is uncertain.

Her closest friend was the botanist Nina Floy Bracelin, who diligently curated the plants Mexía collected. This often involved corresponding with botanists around the world and Bracelin, a woman remembered as a cheerful, friendly person, would have made a better job of this than Mexía would ever have managed. The two women had met as students on a course at the University of California and Bracelin was probably Mexia’s only real friend. The dynamic of their relationship is interesting, for while both women came from similar privileged backgrounds, it was Mexía who held the upper hand. She was the employer and the star of the botanist community. Perhaps they got on so well because ‘Bracie’ could offer friendship without presenting a challenge. Bracelin leaves some of the most insightful comments on Mexía’s personality, that “she loved to travel and to see things and do things, but there had to be a point behind it.” Even here, while praising her friend, Ms. Bracelin seems to be excusing her for some unmentioned abrasiveness.

In 1938, Mexía was once again away on an expedition, this time to Oaxaca, but had to abort the trip due to illness. On returning to the United States, she was diagnosed with lung cancer and died a month later, at the age of 68. Mexía’s contribution to botany was considerable, particularly for a career that started late and was tragically cut short. Yet her achievements must be measured in more than just the number of specimens she brought to the attention of science. She was also an example of what women were capable of, traveling to remote areas in considerable discomfort and occasional danger. As she said herself, “I don’t think there’s any place in the world where a woman can’t venture alone.” It was this example that is perhaps her greatest legacy.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.