Early in 1966, with the Olympics just under three years away, General José de Jesus Clark Flores, President of the Mexican Olympic Committee, oversaw a program to attract international coaches to work with Mexico’s most promising athletes. The Mexican team had returned from the last two Olympics with a single bronze medal on each occasion, and they expected to do better on home soil. After all, the reason for staging these games was to project an image of Mexico as a modern nation.

More than anything else, General Flores wanted a medal in one of the glamor events on the track. It would be tough, as these are among the most competitive events in the Olympic program. There was, perhaps, one opening: the walking races.

In 1966, this branch of the sport had a very small following outside of Europe, and its popularity was declining in the West. The great walkers now all came from Eastern Europe, particularly the USSR. In theory, that meant there were only nine or ten men standing between Mexico and a medal. In addition, these were long distance races, staged over 20 and 50 kilometers, where Mexico City’s altitude would give home athletes an advantage.

Coach Hausleber and Sergeant Pedraza

When the foreign coaches arrived, the Polish Jerzy Hausleber was assigned to the walkers. 36 years old at the time and brought up in the tough neighborhoods around the Gdansk shipworks, it is uncertain if Hausleber had been a competitive walker himself; his main sport was actually boxing. One advantage of his tenure was that he came free of charge, part of an exchange with the Polish government. Hausleber was given just six athletes to work with. Fortunately, one of them was army sergeant José Pedraza Zúñiga.

Pedraza had been raised on a Michoacán ranch where running had been a fact of life. With little prospect of finding work, he joined the army, where he was allowed to play sports. The Mechanized Brigade’s basketball team played in one of the major leagues, and the young José Pedraza was good enough to be selected for a few games. He could dribble and score points on a break, but was too small to have any great impact on a sport where height ruled.

Instead, Pedraza started to concentrate on athletics. He came close to making the Olympic team in 1960 and 1964, but at 27, that dream seemed over. There was still promise in Pedraza, however: he had just won the first ever Mexican walking championship. Within weeks of Jerzy Hausleber’s arrival, Pedraza also won the Central American and Caribbean Games title.

The significance of this win should not be overestimated: Pedraza’s race was staged over 10 kilometers, half the Olympic distance, and none of the countries in the region had a walking tradition. However, winning was a confidence booster and it whetted the squad’s appetite for more and greater success. Hausleber and “El Sargento” Pedraza buckled down to work.

“La Marcha” is born

Hausleber identified a problem. Walkers at the time tended to take long strides, keeping their heads and shoulders stiff. This style that favored taller men, but most of the Mexican squad was short and stocky. If Hausleber couldn’t make his walkers taller, he would find a technique more suited to their build. And so “la marcha” was developed.

Traditionally, racewalking was just a faster version of normal walking, with the feet moving in parallel, the width of the athlete’s hips apart. In “la marcha,” the athlete places one foot directly in front of the other to move along a narrower line. Every time we take a normal walking step, we twist our hips about four degrees. Modern racewalkers, using Hausleber’s gait, twist closer to 20 degrees. In addition, instead of keeping the trunk and head in the rigid posture of the Europeans, Mexican racewalkers became far more flamboyant, throwing their head, shoulders and trunk around. In other words, the new technique made walking more fun to take part in and more exciting to watch. Still, it was not an easy adjustment, and Hausleber developed a whole series of exercises and training routines for his walkers. These are still used around the world today and are known as the Mexican Drills.

The new style was fast, and it suited the Mexican team, but it also created a potential problem with judges. Walking is defined as having one foot in contact with the ground at any one moment. If both feet lift off the ground simultaneously, it is considered running. The term used in racewalking is ‘flight time’; if noticed by the judges who are spread around the course, it earns a warning. Three warnings means disqualification. However, the sport’s rules stipulate that flight time has to be visible to the human eye. It is estimated that “la marcha” squeezed in about 40 milliseconds of flight time on each step: too fast for the human eye to spot. There was some uncertainty if the new style would be accepted, or the rules changed to outlaw it.

The speed of the Mexican team’s progress was remarkable. Within a year of Hausleber’s arrival, the Mexicans were recording world-class times. In 1967 they made their debut on the European circuit, where they held their own against — and sometimes beat — some of the best walkers in the world. After competing in the USSR, the team traveled to Winnipeg, Canada, for the 1967 Pan American Games. Here Pedraza moved into the big leagues with a silver medal.

Mexico City, 1968

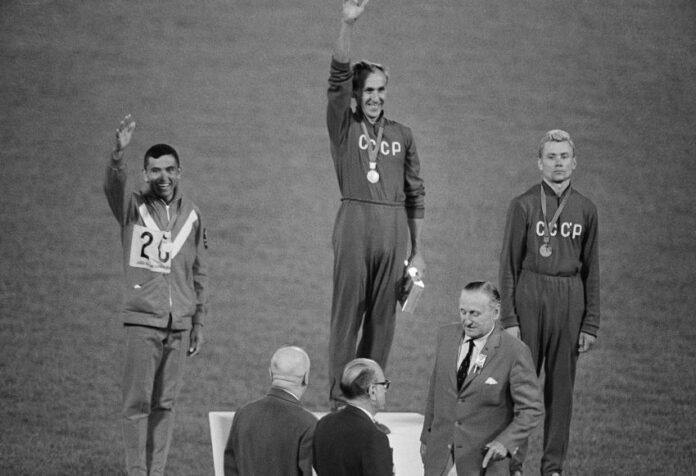

Fast-forward to Oct. 14, 1968, the second day of the track and field program at the Mexico City Olympics. The walkers completed a half lap of the stadium and, with Russian champion Vladimir Golubnichiy already in the lead, headed out for the surrounding roads. Some 90 minutes later the leaders returned, still led by Golubnichiy, who had a narrow lead over teammate Nikolai Smaga. Then there was a cheer from the crowd, for in third place was José Pedraza.

Pedraza looked safe for the bronze medal but seemed too far behind the Russians to make any headway over the last three quarter laps of the track. The Mexican had other ideas: with the crowd calling his name, he raced past Smaga. Golubnichiy was the finest walker of his generation and managed to hold out, beating Pedraza to the line by a second.

It was probably just as well. As the British magazine Athletic Weekly said in a review of Olympic walking, “in the views of most experts, Pedraza was not walking legally but there seemed little chance he would be disqualified as he closed up on Golubnichiy with officials fearing a riot.” Russia had no wish to deprive the host nation of a medal, so they settled for gold and bronze. Had José Pedraza passed Holubnychy and won the gold, there would almost certainly have been an appeal which would have likely turned into a major diplomatic incident.

The Mexican racewalking revolution

A silver medal, won in such dramatic fashion, laid the groundwork for a walking revolution in Mexico. Hausleber was invited to stay on as coach, and money was found to fund a long-term program. Walking slowly became one of Mexico’s national sports, but it did so primarily as a spectator sport, with big street races drawing large crowds and television cameras.

Munich in 1972 brought steady, if unspectacular, progress, but it wasn’t until the kids who had watched the drama of the 1968 race were coming through the system that the golden age of Mexican walking arrived. This cohort’s highlight was Daniel Bautista winning the Olympic title in Montreal in 1976.

Walking is about more than just the Olympics, however. Every two years the best walkers in the world gathered for the Lugano Cup, a team world championship which Mexico won in 1977 and 1979. And the nation’s impact goes beyond mere medals. The Mexican style of walking was adopted around the world and the best international walkers came to Mexico to train. This was partly for the altitude, but there was also the feeling that Mexico was now the center of the sport. Visiting athletes spoke in awe of both the hospitality and the tough training schedules the Mexican walkers were putting themselves through.

The 1984 Olympics brought even more success, with Daniel Bautista winning the 20 km gold and Raul González securing the 50 km gold and 20 km silver. Perhaps the greatest athlete of them all was Ernesto Canto, who openly acknowledged the inspiration of José Pedraza and the coaching of Hausleber. A wonderful technique and hard work brought Canto Olympic, World and Pan-American titles.

Canto might be considered the last of the Golden Generation, and after he retired Mexican dominance started to fade. To be sure, Mexico still produces world-class walkers, such as Daniel García Córdova and Lupita González. However, there have been no Olympic titles since 1984. This decline was partly because Jerzy Hausleber was losing energy. With heart and knee problems, he increasingly restricted himself to coaching coaches and promoting the sport with motivational speeches. Although he was always diplomatic, he hinted that, in his opinion, many young Mexican walkers no longer had the work ethic that had taken athletes like Canto to the very top of their sport.

As for Jerzy Hausleber, he became a Mexican citizen in 1993 and died in 2014 at the age of 83. He is still remembered both as an extraordinary coach who guided Mexican walkers to 118 medals in major championships and, in the words of Canto, as “a great person and extraordinary human being.” José Pedraza Zúñiga, Hausleber’s greatest pupil, stayed in the army, reaching the rank of captain and continuing to coach young walkers. He died in 1998, at the age of 61.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.