Few Mexican athletes have enjoyed the global success of the country’s boxers. Since almost the first instant of prizefighters lacing up gloves and commencing battle south of the Río Bravo, Mexican pugilists have experienced significant periods of supremacy on the international stage.

The sport has profoundly affected Mexican society. Over the course of the 20th century, boxing inspired movies, songs and specific notions of Mexican identity. It became a source of civic pride for downtrodden communities, a propaganda tool for politicians and a national obsession.

In part one of our series on the history of boxing in Mexico, we’ll trace the sport from the moment of its arrival, through its first golden age to the eve of Mexican boxing’s second glorious era.

Boxing arrives in Mexico

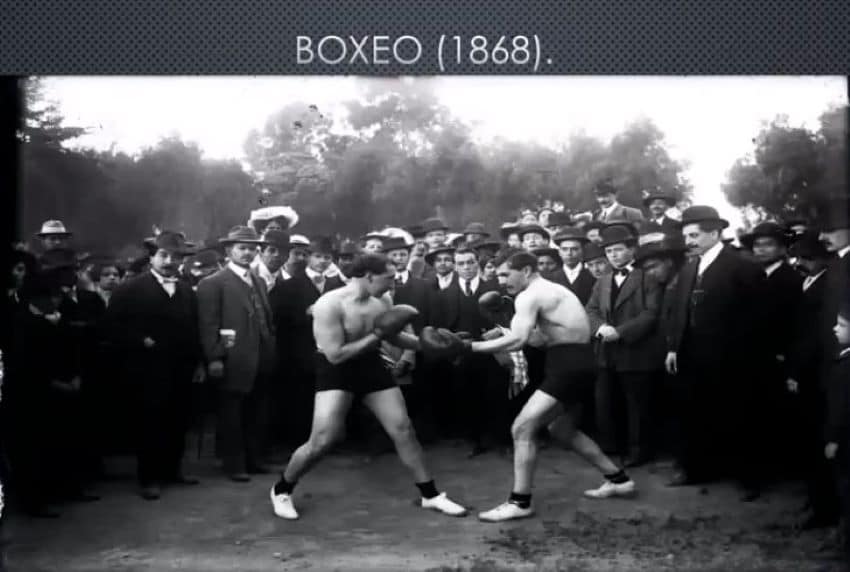

Ritualistic boxing in Mexico dates back to Mesoamerican civilizations including the Olmec and Zapotec. But the version of the sport practiced here today, based upon the now-ubiquitous Marquess of Queensberry Rules, originates in 19th-century England. Though it was hoped that rule changes such as the introduction of standardized gloves and timed rounds would legitimize boxing and dampen growing calls for its prohibition, they failed to stem boxing’s declining popularity in Britain. And as the sport was pushed further underground, many of its practitioners sought new opportunities in the United States, and eventually Mexico.

According to historian Stephen Allen, boxing in Mexico dates back to at least 1887, when an illegal match was stopped by authorities who deemed it an expression of moral degradation. Nonetheless, it’s believed that illicit fights continued into the 1890s, often patronized by British and American expatriates.

When dictator Porfirio Díaz gave boxing his approval in 1894, the sport gained an air of respectability. Though it was not until the 1910s, amidst the disarray of the Mexican Revolution, that its popularity surged. After the revolution, the Mexican government sought to use major sporting events to bolster its perceived stability on the world stage. Boxing featured heavily in this strategy, and major fights were held at Mexico City’s Frontón Nacional throughout the 1920s.

Though most of these contests featured fighters from north of the border, the gymnasiums and rudimentary governing bodies established during this period laid the foundations for Mexico’s first generation of spectacular boxers. By the late 1920s, Mexico City was producing its own array of noteworthy talents, a number of whom would come to represent Mexico’s first golden age of boxing.

The first golden age of Mexican boxing

Mexico’s first golden age of boxing is widely regarded to have lasted from 1933 to 1936. While the improved caliber of Mexico’s best fighters meant that many plied their trade in the United States, this period also witnessed a large number of high-quality bouts — featuring both Mexican and international competitors — at Mexico City’s Arena Nacional. Domestic fans were able to watch the best fighters in the world, including their own compatriots, and crowds at the Arena frequently filled its 30,000 capacity.

Notable among Mexico’s heroes of the golden age is Luis Villanueva Páramo. Known affectionately as Kid Azteca, Páramo is credited with popularizing the infamous Mexican liver punch: a hook to the right side of an opponent’s body which, when landed properly, bludgeons the liver and incapacitates its sorry proprietor for the duration of the ten count. The shot remains a key component of the acclaimed Mexican style of boxing almost 100 years later.

The Champion without a Crown

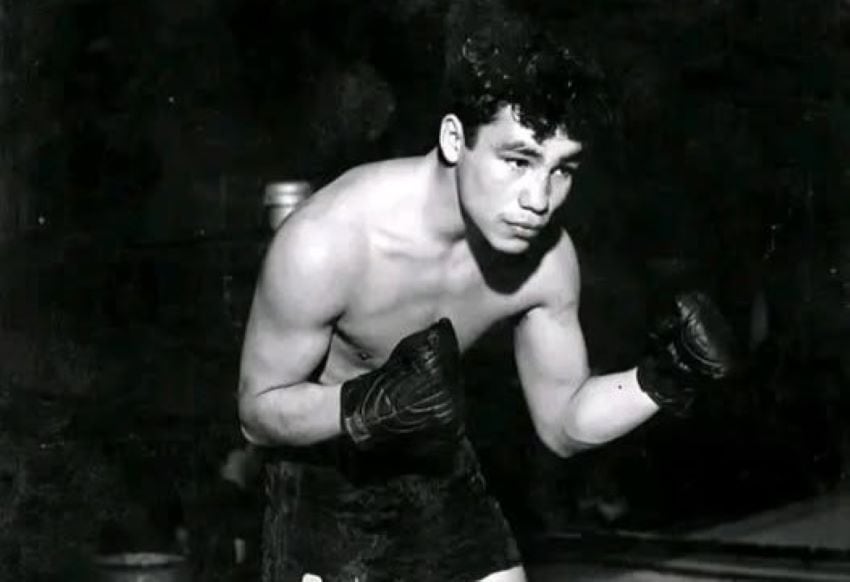

Though perhaps the most fitting symbol of the first golden age is Rodolfo “El Chango” Casanova. Casanova moved to Mexico City with his family after his father, an officer in the military, was killed during the Mexican Revolution. They lived in the working-class neighborhood of La Lagunilla, where Casanova worked numerous jobs as a child before eventually discovering boxing.

Casanova’s rise was phenomenal: within six months of his first professional bout he was beating established opponents before crowds of up to 20,000 people and impressing fans in both Mexico City and Los Angeles. But the excesses so often concomitant with success were to be his undoing. Newspapers soon bore tales of Casanova’s nocturnal habits, his excessive drinking, and an alleged romantic affair with Hollywood starlet Mae West. In spite of his prodigious talent, Casanova never became world champion.

The allegorical appeal of Casanova’s rise to glory and subsequent fall from grace made it the subject of the 1945 film “Campeón sin corona.” Casanova sought remuneration from the film’s producer, Raúl de Anda, before embarking upon a 50-hour hunger strike outside the National Palace. The two never reached a settlement, and de Anda’s film enjoyed box office success and critical acclaim while Casanova lived out the rest of his life in poverty.

Mexican boxing’s interregnum

A final, symbolic footnote to the first golden age was written on the site of the Arena National. With the international success of Mexican fighters dwindling towards the end of 1936, the venue that had hosted some of their greatest accomplishments burned to the ground, in suspicious circumstances, in February of the following year.

However, the ensuing decades were not entirely devoid of ceremony. While the next era of Mexican boxing lacked the romance of those which enveloped it, it would not be without its own distinguished figures.

The spiritual home of Mexican boxing could conceivably be pinpointed to a single square-kilometer block of the country: the Mexico City neighborhood of Tepito. The ”barrio bravo” is renowned for its combative residents and unforgiving boxing gyms that have produced a number of world-class fighters.

Today, the symbol for the Tepito metro station is a boxing glove. In the early twentieth century, when Mexico City’s political and social elites condemned the neighborhood as a bastion of crime, illiteracy and moral degeneracy, its champion fighters provided a valuable counterpoint for Tepito’s proud and defiant community.

The Tepiteño fighters and a history of Mexican boxing legends

Tepito’s list of famous sons includes names like Rubén “El Púas” Olivares, Carlos “El Cañas” Zarate and the aforementioned Kid Azteca. But its most loved is arguably Raúl “El Ratón” Macías. His 1954 fight against the American Nate Brooks drew over 50,000 spectators to Mexico City’s Ciudad de Deportes to watch him claim the North American bantamweight title. Many of the city’s higher-ranking professionals are said to have sent employees to stand in line for tickets at the box office a week ahead of the fight.

Contemporaneous press reports from the fight stress the wide cross-section of Mexican society that turned out to support a young man from the city’s so-called slum. Though Macías earned the affections of the entire nation, he never shirked his role as Tepito’s unofficial ambassador.

In stark contrast to the popularity of Macías was the public perception of fellow great Vincente Saldívar. Another Mexico City native, Saldívar claimed the world featherweight title in September 1964 and defended it eight times before his first retirement in 1967. One such defense, made in London against the Welshman Howard Winstone, was televised as part of the first satellite broadcast in Mexican history. Yet Saldívar’s apparent lack of warmth, and his public assertions that he fought for himself and not the Mexican nation, meant he never received the adulation enjoyed by compatriots such as Macías.

Saldívar did, however, earn the widespread approval of the nation’s politicians. While the practice of using boxers’ successes to promote the government was not new, Saldívar’s reputation as an ascetic endeared him to presidents Adolfo López Mateos and Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, both of whom made public displays of their support for the champion.

For elites who had long used athletes to project acceptable forms of Mexican identity and morality, Saldívar’s talent and probity made him the ideal poster boy for national progress. But it would be the next generation of fighters who captured the hearts of the Mexican people.

Though perhaps simplistic, it could be argued that the first golden age of boxing in Mexico lent itself to romanticism, while subsequent decades contained genuine examples of pure sporting achievement. The second golden age would do both.

Ajay Smith is a freelance journalist and ghostwriter from Manchester, England, now based in Mexico City. His areas of specialization include boxing, soccer, political history, and current affairs. Samples of his work can be found at ajaysmith.com/portfolio.