When and where — and by whose efforts — women’s soccer first appeared in Mexico is likely never to be identified. But the earliest documented event is the arrival of a women’s team from Costa Rica that made a long tour around the country in 1963.

Their arrival didn’t introduce women’s soccer to Mexico but it certainly contributed to its growth. Around Mexico, a few enthusiastic young women recruited friends and assembled teams to play the Costa Rican visitors — and carried on playing afterward, which would lead within just a few years to Mexico creating a women’s national selection team and even hosting the newly created Women’s World Cup — to great success.

How did this happen?

By 1969, there was enough enthusiasm to stage the first Mexican women’s championship, a competition involving 17 teams from around Mexico City. At this point, the situation in Mexico was very similar to that of women’s soccer in Europe — where a handful of clubs operated under the radar, and usually without any recognition or assistance from the male-dominated associations.

A World Cup for women’s soccer

The pockets of enthusiasm in Europe had gained enough traction in the 1960s to form the Federation of Independent European Female Football (FIEFF). In 1969, it organized a World Cup competition for women’s soccer.

Italy, who had led the way in women’s soccer in 1968 with a nationwide and semiprofessional women’s league, was the natural host, but how Mexico came to be one of the eight invited teams remains a mystery. We do know that they were not on the original list of competing teams and were only included only after Argentina and Brazil dropped out.

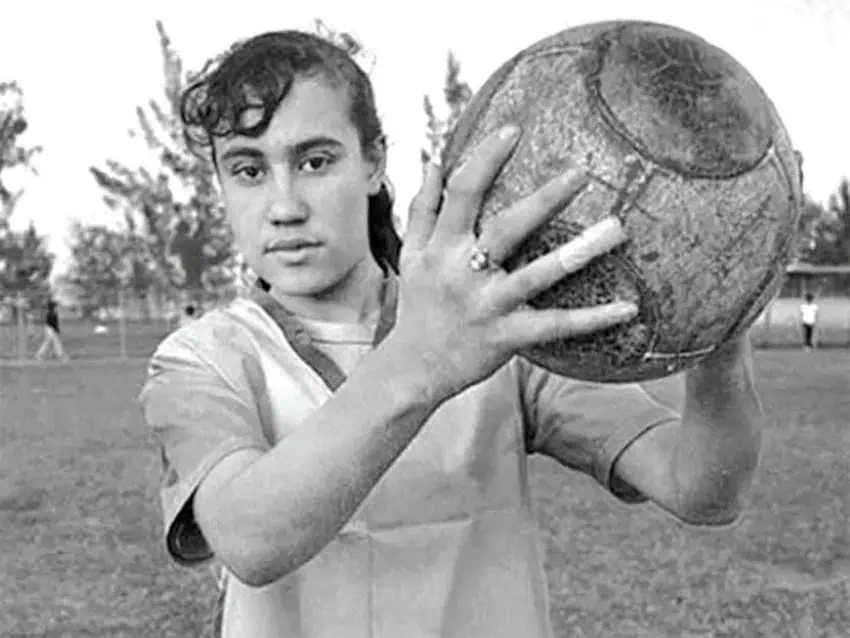

The Mexican team played its first game in the city of Bari, beating Austria 9-0 and throwing Alicia Vargas into the spotlight with four goals.

Vargas’ story is worth following, as it is typical of so many women players of this generation. She had played soccer with her brothers and neighborhood boys in the street and — without realizing it — became a skilful player. When she was just 13, she saw more organized games involving the Guadalajara club and asked if she could join in. Despite no formal training, the skills she’d picked up on the street made her an instant star.

In Italy, she became “La Pelé” Vargas and was offered a contract to stay on to play with the Real Torino team, but she chose to return to Mexico.

During a two-day conference after the Cup in Torino, Mexico’s representatives agreed to host the next tournament. The Federation of Mexican Football, however, opposed the idea and threatened fines on any club that granted women access to their stadiums.

The organizers got around this by hiring the Estadio Azteca in Mexico City and the Estadio Jalisco in Guadalajara. Both stadiums were privately owned and therefore beyond the control of the Federation.

This had an unforeseen impact on the event. Both stadiums were owned by media outlets wanting a successful tournament. Their backing meant there would be no lack of advertising or media coverage. In addition, the Italian Martini & Rossi company covered the cost of hotels, flights and equipment for the Mexico event.

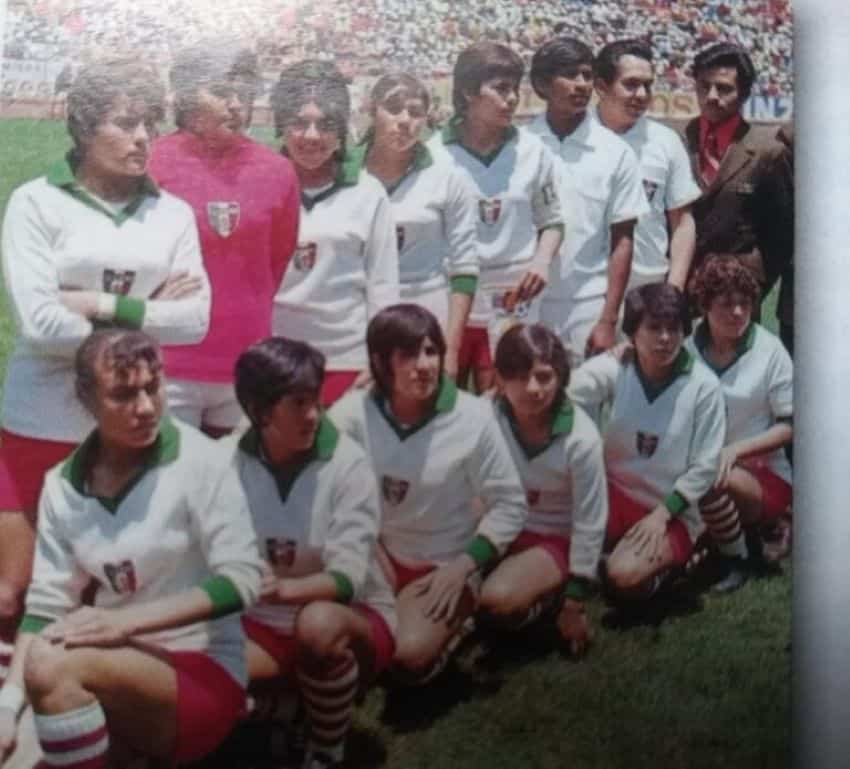

Planners invited Argentina, Denmark, England, France and Italy to join Mexico in the tournament. Team members arriving in Mexico City found the city swamped with posters and banners for the event. Central to the advertising campaign was Xóchitl, the tournament’s mascot, a dark-haired little girl with pigtails who wore a red, white and green uniform jersey and short shorts.

Back then, even though several of the players on many of the teams, Mexico’s included, were minors as young as 13, organizers were not shy about using the team’s gender and sexuality to fill stadiums. The goal posts were painted pink. In between playing and attending a press interview, the players were encouraged to use the beauty salon situated inside the locker rooms.

“Soccer,” the New York Times reported at the time, “goes sexy south of the border.”

While this grates with today’s attitudes, organizers argued that the makeup and glamour wasn’t just to encourage men into the stadiums but also to show young women that sports could be feminine and cool.

The advertising paid off. Helped by live TV coverage, matches averaged crowds of 15,000, and Mexico’s games in the Aztec Stadium probably — there were no official figures — attracted 100,000 fans. For the competitors, used to playing on local park pitches, it was an unbelievable experience.

Off the pitch, they were superstars, with crowds gathering outside their hotel and mobbing the team coaches. The fans included a few lovesick young boys with bunches of flowers!

The Mexicans had been training for two months and were well prepared. They won both their group games and then beat Italy to make the final. The standard of play was “okay.” The Mexican team had good basic ball control, and there was a willingness to run with the ball. However, the games lacked pace, and defenders often needed an extra touch to control the ball, allowing them to get robbed close to their own penalty area.

Overall, as to be expected, there was also a lack of power compared to the men’s game, and goal kicks usually landed well short of the halfway line.

Mexico had done well in making the final, but not all was well behind the scenes. With the tournament drawing in considerable revenue, the Mexican team asked for the creation of a bonus fund that would be split between them. Disputes over this distracted the team in the days before the final game.

Even so, the Danes were the outstanding team of the tournament, and it is doubtful that the squabble in the Mexican camp had any real impact on the result. In the end, Denmark’s 15-year-old Susanne Augustesen scored a hat trick to guide her team to the title.

A stunning 110,000 spectators packed the Estadio Azteca for that game, and coach Harry Batt felt a corner had been turned.

Footage from the Mexico vs. Denmark final in 1971 in Mexico City, in which Denmark’s 15-year-old Susanne Augustesen took her team to victory against Mexico.

“I am certain,” he told the press on his return to England, “that in the future, there will be full-time professional ladies’ teams in this country.”

His team returned home with their suitcases so full of souvenirs that some worried about getting through customs. However, they left the fervor of 100,000-spectator crowds only to return to a wall of indifference back home. One player, invited to join her heroes Newcastle United at a club dinner, sat through a comedian whose main act was to ridicule women’s football. The young players who returned to school were not acknowledged in assembly.

And not just male authorities were indifferent: An official Women’s Football Association had just been formed, and although it had declined to send a team to Mexico, the association’s officials were furious at Harry Batt for what they saw as going behind their backs. Batt found himself blacklisted by the Women’s Football Association.

It was not only the English authorities cold-shouldered their team returning from Mexico. A couple of years later, the Danish Football Association (DBU) took over the running of women’s football in Denmark and launched an official national team. Games were few and far between, and they never called up Augustesen for an official international, even though she had become one of the great stars of the Italian professional league.

It was much the same story for the Mexican team. The press and cameras departed, and those who carried on playing did so on dusty second-rate pitches, relying on volunteers to keep the teams going. Internationally, there were a few more competitions, the mundialitos, but they were minor events, usually staged in Italy over the duration of a week for six invited teams. Mexico participated in the 1986 event but struggled in a tournament that nobody suggested had world championship status.

Memories of the 1971 World Cup faded, and the tournament had little impact on the later development of women’s football. That revolution was driven by events in the United States. In 1975, Pele joined the New York Cosmos, and soccer suddenly became the most popular sport for children in the U.S. It didn’t require the expensive equipment of baseball or American football, or carry the dangers of the latter.

Americans knew nothing about soccer, including the fact that only boys were supposed to play, and so a generation of American girls grew up playing soccer in mixed games. By the time an official Women’s World Cup started in 1991, U.S. women’s soccer was the world superpower, doing better than its male counterparts, winning two of the first three tournaments and attracting a 94,000 crowd for the 1999 final in Pasadena.

The men who controlled the game slowly came to realize that soccer was a business — and in what business plan did it make sense to deliberately exclude half of the world’s population? With FIFA’s blessing, women’s soccer has gone from strength to strength.

Mexico has been somewhat left behind by the modern growth of the women’s sport, although that gap is closing. Today, the Mexican women’s professional league is in its ninth season, with wide television coverage and sponsorships allowing players to earn a reasonable monthly wage — about the same as a well-paid teacher in a private school.

Attendance hovers around 3,000, good compared to other women’s leagues around the world but dwarfed by the crowds watching men’s games. While Amelia Valverde Villalobos has done well at C.F. Monterrey, and Mónica Vergara has coached the national team, the coaching positions with the big female teams remain stubbornly filled by men.

The Mexican national team ‘El Tri Femenil’ has not become the regional power in the way that the men’s team has been for generations. They have not qualified for the World Cup since 2015, and after a disappointing performance in the 2022 CONCACAF championship, the team will miss the next round of big international tournaments.

As women’s soccer around the world moves slowly but steadily towards equality, the girls of 1971 are finally gaining some recognition. A movie about the Mexican World Cup, “Copa 71,” premiered at the 2023 Toronto International Film Festival to positive reviews. Yet, the battle for equality is ongoing.

A documentary produced by Venus and Serena Williams, “Copa ’71” tells the story of the 1971 Mexico City Women’s World Cup via interviews with many of the participants.

As late as 2016, Barcelona FC was slammed online for sending its men’s and women’s teams to the same tournament, giving the male players business-class tickets while the women’s team flew economy.

However, the fact that this was recognized as an injustice perhaps shows how far we have progressed.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.