Growing up in Durango, not far from the southern Chihuahua border, I often heard passing mentions of the Indigenous Tarahumara. People would reference the mountains or “those Indigenous runners” with awe but never much depth. It wasn’t until adulthood, after moving away and returning with more curiosity, that I began to understand who they are — and why their story matters.

Known as the Rarámuri (their own name for themselves, translated as “those who run fast” or sometimes as “light-footed”), they are among the world’s greatest endurance runners. They live deep in the Sierra Tarahumara, a dramatic and rugged stretch of northern Mexico’s Copper Canyon, an area four times the size of the Grand Canyon.

Yes, they are incredibly fast. But what makes the Rarámuri’s running so remarkable isn’t just physical ability — it’s that running is a reflection of how they live, what they believe and how they’ve stayed connected to their traditions in spite of everything history has thrown at them.

A lifetime of movement

The Rarámuri have lived in Chihuahua for centuries, long before colonization pushed them into the high sierras. Those who retreated deeper into the canyons were never fully conquered, preserving a way of life that still resists full assimilation.

Today, estimates vary, but anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 Rarámuri live across the Alta and Baja Sierra, continuing traditions passed down for generations.

One of those traditions is running. Rarámuri children don’t train for races — they run because it’s how they get around. The terrain where they live is steep and wild. Villages can be hours apart on foot. Over time, their bodies adapt: wide feet, strong joints, incredible stamina.

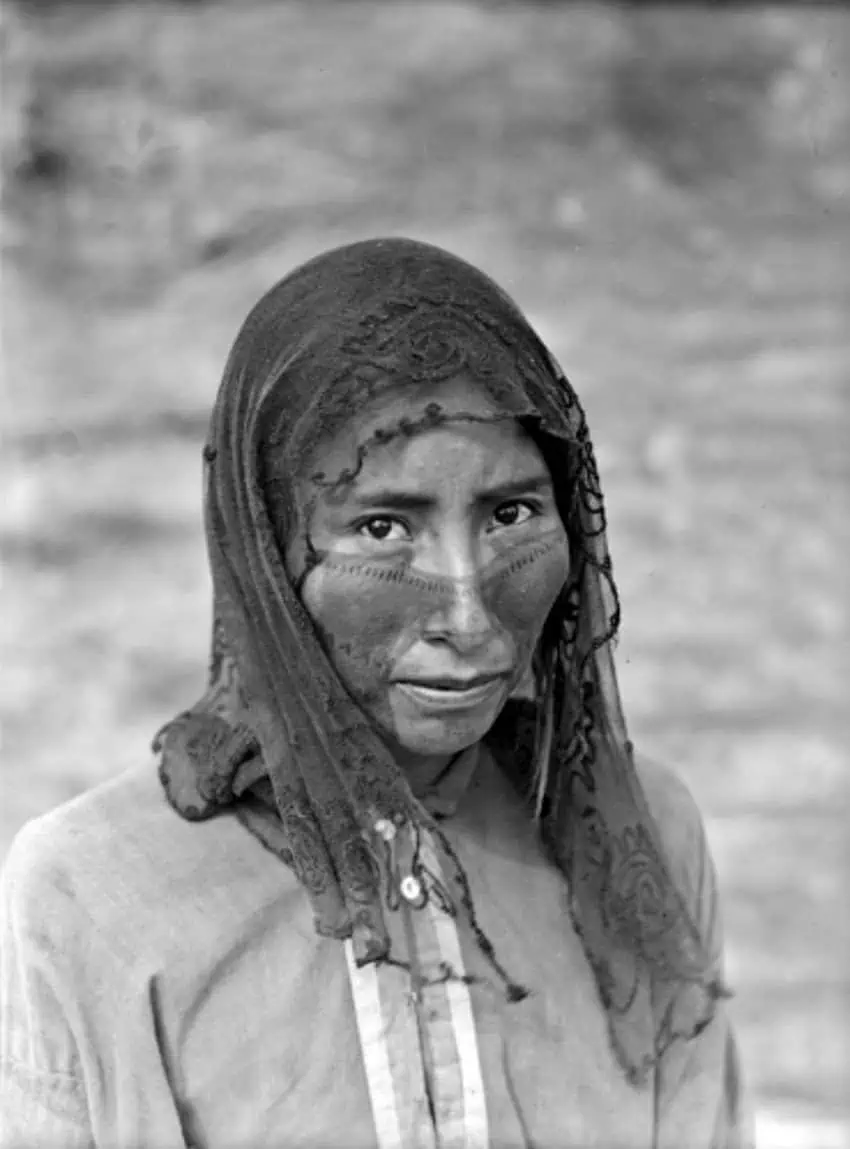

They often run in huaraches, handmade sandals fashioned from leather straps and the rubber from old car tires. Their feet are wide from a lifetime of movement, and modern sneakers can feel constricting. Studies suggest their minimalist footwear helps promote a more natural, injury-resistant stride.

Their diet also supports endurance. Take pinole, a simple but powerful mix of roasted ground maize and water. It’s nutrient-dense, slow-burning and provides sustained energy over long distances.

Their movement is woven into their lifestyle, their food and their connection to the land.

The Rarámuri have traditional footraces still practiced today. Rarajípare is a game where men kick a wooden ball ahead while chasing it over long distances. Ariwete, played by women, involves a hoop and stick. These events can go on for hours, or even days, especially when played between villages.

The spirit behind them isn’t just competition — it’s something deeper. Races are often preceded by a yúmari, a spiritual ceremony where runners are reminded to run with unity and for a purpose. Winning matters but so does how the race is run. As one phrase captures it: Iwériga — “send the power of your soul to another.”

Traditionally, the Rarámuri also hunted by chasing prey to the point of exhaustion. Running was — and still is — survival. But it’s also a form of gratitude and prayer deeply embedded in their cultural and spiritual life.

What the world gets wrong

The global spotlight found the Rarámuri after the 2009 release of “Born to Run,” a best-selling book that chronicled their ultradistance abilities. But even well-meaning stories often drift into caricature — calling them superhuman, mystical, or natural-born athletes with supernatural pain tolerance.

This kind of praise flattens the truth: The Rarámuri are not magical anomalies. They’re people who have maintained an active, community-centered way of life for centuries. They’ve adapted to extreme terrain, preserved ancient practices and endured repeated waves of violence and environmental destruction.

Despite staying largely out of the spotlight, many Rarámuri have earned national and international recognition in competitive races. One of the most famous is Lorena Ramírez, who made headlines in 2017 when she won the 50-kilometer UltraTrail Cerro Rojo in Puebla. She did so wearing a traditional dress and huaraches, finishing in just over seven hours.

Her story was captured in the short documentary “Lorena, Light-Footed Woman,” which highlights not just her strength but the quiet pride and cultural grounding that fuel her.

In 2024, six Rarámuri women made history by completing The Speed Project, a grueling 540-kilometer relay from Los Angeles to Las Vegas. It was the first time Indigenous Mexican women had participated in the race.

Their names — Verónica Palma, Ulisa Fuentes, Isadora Rodríguez, Lucía Nava, Rosa Para and Argelia Orpinel — now join a growing list of Rarámuri runners who’ve quietly reshaped the global narrative about endurance and strength.

Rocio is a Mexican-American writer based in Mexico City. She was born and raised in a small village in Durango and moved to Chicago at age 12, a bicultural experience that shapes her lens on life in Mexico. She’s the founder of CDMX IYKYK, a newsletter for expats, digital nomads, and the Mexican diaspora, and Life of Leisure, a women’s wellness and spiritual community.