When the Ricardo Legorreta Vilchis designed Camino Real Polanco hotel opened in Mexico City in 1968, three months before the city hosted the Summer Olympics, it was immediately hailed as an architectural masterpiece.

Its most arresting singular feature is undoubtedly the “Fountain of Eternal Movement” crafted by famed landscape architect Isamu Noguchi, which, rather than mimicking the serene or stately welcoming fountains customary at other properties, instead provides a welter of violent motion. The hotel’s overall aesthetic, however, is heavily indebted to Legorreta’s creative modernist design sense, and in particular, his passion for vibrant colors.

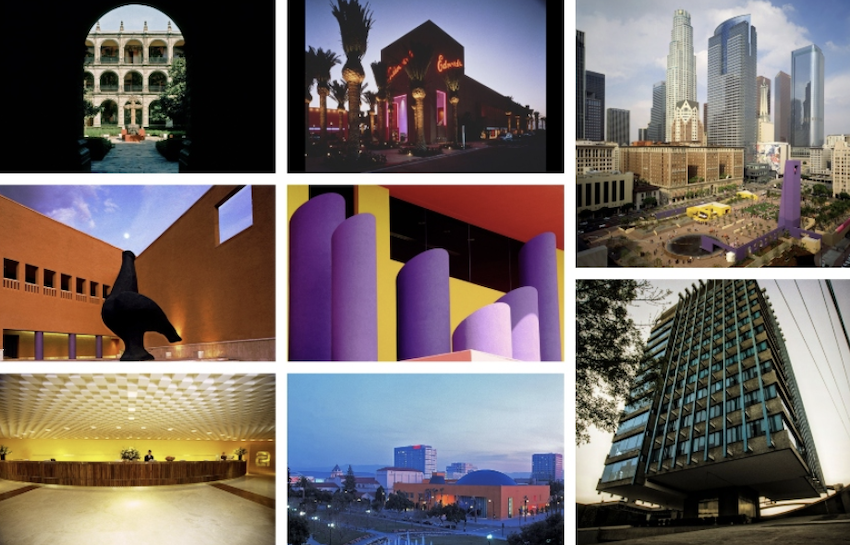

Its often photographed entrance gate, for example, is a vivid magenta-pink latticework set off by a bold yellow adjacent wall. This kind of unmistakable color signature would become a staple of the 100-plus projects — including numerous hotels and museums, as well as private homes and public works — Legoretta designed before he died in 2011, and helped cement his reputation as one of the greatest of all Mexican architects.

Legorreta’s conception of color

Legorreta’s understanding of color’s ability to evoke emotional responses is something he no doubt learned from his teachers while studying architecture at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (UNAM) in the late 1940s and early 1950s. It was certainly fostered by mentors like José Villagrán García, the “father of modern Mexican architecture” and the man who hired him even before he graduated, and also influenced by legendary architect Luis Barragán when the two became friends during the 1960s.

However, according to Legorreta, the man who most significantly molded his thinking on the topic was Chucho Reyes (born Jesús Reyes Ferreira), the self-taught painter who, like Barragán, hailed from Guadalajara. To Legorreta, Reyes was “the master of color, the one who taught us everything.” Indeed, one has only to look at Reyes’ work to see the bright, brilliant purples, blues, and yellows that would later become touchstones in Legoretta’s designs, from the 10-story purple campanile in Los Angleles’ Pershing Square (1993) to the bold blues that seamlessly integrate the Tech Museum of Innovation in San José, California (1998) into its surrounding environment, and the eye-catching yellows evident in his Casa Greenberg (1991), and in his first landmark Camino Real.

This blending of these vibrant colors into a rich symphony — the artistic term is polychromy — was always intentional in Legorreta’s work, and was meant to serve a specific purpose. As he once noted, color “dramatizes, evokes, produces emotional responses, intensifies personal experience, provides energy to spaces and reinforces their presence.” So sensitive was he to these emotional currents that he would choose colors able to reflect changing moods as the natural light shifted in intensity throughout the hours of each day.

Such sensitivity would be remarkable in any artist, but it was particularly striking in one brought up in a family of bankers.

The evolution of Legorreta’s aesthetic

Born into privilege in 1931 as the scion of one of Mexico’s wealthiest and most socially prominent families, Legorreta could easily have followed in the footsteps of his father, Luis, and uncle Agustín, who founded the country’s biggest bank (BancoMex). But by the time he was a teenager, he knew he wanted to be an architect. After studying at UNAM and spending a little over a decade as an apprentice and later partner of Villagrán, he opened his own company, Legorreta Arquitectos, in 1963.

His first signature design, for an automobile factory in Toluca, was a liberating experience and an assertion of his very Mexican sensibilities. “When I built Automex, it was like an explosion inside me,” he recalled in 1995, per the Los Angeles Times. “A rebellion against all the discipline I had known and the foreign domination of my country. It was like yelling ‘Viva Mexico!’ and ‘Viva the Mexican worker!’”

With the success of the Hotel Camino Real in 1968, he was recognized not just as a promising disciple of Villagrán and Barragán, but as a mature, independent artist. The opening of the hotel was attended by President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and his uncle Agustín Legorreta López Guerrero. Both were reportedly also investors, his uncle in his then role as president of Banamex. More commissions rolled in, including for other Camino Real hotels in Cancún and Ixtapa.

Legorreta’s work in the U.S.

Although most of his designs continued to be located in Mexico, with at least a dozen in his native Mexico City alone, by the 1980s Legorreta was also increasingly receiving commissions from international sources. These raised his global profile, but also brought controversy, as critics in other countries, like the U.S., weren’t always as at ease with his distinctly Mexican design philosophy. Purple walls at his design for the $90 million Tustin Market Place shopping center in California in the mid-1980s, for instance, were decried by the town’s mayor as “too garish, too oppressive,” obliging Legorreta to replace them with a more acceptable ocher hue.

“The incident taught me something about the profound differences that lie beneath the surface similarities Southern California shares with my homeland,” Legorreta admitted at the time. “Though the climate and topography are similar, and also much of the cultural heritage, California society is simultaneously more confident and less bold than ours, and this difference is reflected in the architecture.”

Indeed, few architects have ever embraced boldness like Legorreta, especially when it came to color. And lest one thinks the Tustin incident caused him to reconsider his principles, his Pershing Square project in Los Angeles a few years later centered around a 125-foot-tall purple bell tower. That too was controversial, but he never considered changing it.

Legoretta’s death and legacy

For the last 20 years of his life, Ricardo Legorreta collaborated with his son Victor. Since his death from liver cancer at the age of 80 in 2011, Victor has continued his father’s legacy via Legorreta + Legorreta. It’s hard to imagine anyone matching Ricardo’s flair for color, but based on the stunning collaboratively designed Papalote Children’s Museum — only four kilometers from the Camino Real in Mexico City — an eye for color may be a talent that runs in the family, just as banking once did.

Chris Sands is the Cabo San Lucas local expert for the USA Today travel website 10 Best, writer of Fodor’s Los Cabos travel guidebook and a contributor to numerous websites and publications, including Tasting Table, Marriott Bonvoy Traveler, Forbes Travel Guide, Porthole Cruise, Cabo Living and Mexico News Daily. His specialty is travel-related content and lifestyle features focused on food, wine and golf.