As much as Florida is associated with these funny pink birds, perhaps it is better to think of them as Mexican.

The world has six species of flamingos, but the American flamingos (Phoenicopterus ruber) are famous for their color, which is a result of their diet, not genetics. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimates that there are over 200,000 of the birds over their home range that extends from southern Florida, over the Caribbean and into South America. Exact numbers are hard to come by because the birds are migratory, flying anywhere from hundreds to thousands of kilometers to take advantage of certain feeding grounds and nesting sites in multiple countries.

Estimates as to how many touch down in Mexico range anywhere from 20,000 to about 40,000, linking Mexico to the flamingos’ ecological niche. For this reason, Mexico works both within its borders and beyond to better understand and conserve the species.

Flamingos congregate on the northern coast of the Yucatán peninsula, in particular four important federally-protected areas: Los Petenes, on the northern edge of Campeche; Ría Celestún Biosphere on the western edge of Yucatán (state), Ría Lagartos on the eastern side of the same and Yum Balam Flora and Fauna Protection area in northern Quintana Roo.

Petén, Celestún and Yum Balam are all stopovers and feeding areas for migrating flamingos, but Ría Largartos is particularly important because it is Mexico’s principal nesting site, and the second most important after Cuba.

All of these sites allow visitors, but how many flamingos you might see will vary depending on the time of year and the quality of feeding in any given year. The two most popular are Celestún, best from October to April, and Ría Lagartos, during the breeding season from April to August/September.

Although not considered endangered internationally, the Mexican Environment and Natural Resources Ministry (Semarnat) lists them as protected, as human activities such as boating and water contamination negatively impact their habitats. The birds are sensitive to both because they live and feed in shallow brackish waters on the coast, straining larvae, small crustaceans and more from the sediment they kick up.

Conservation efforts have been going on in Mexico for decades, and may be why there are any wild flamingos at all in the United States.

Although tagging and monitoring has been going for more than two decades, efforts really stepped up when the National Commission for Protected Natural Areas (Conanp) teamed up with the Pedro and Elena Hernández Foundation in 2015, bringing in support from other non-profits and Mexican corporations to systematically study the birds and improve their Yucatán habitats. These organizations include the National Autonomous University of México (UNAM), and tourism heavyweights such as the Xcaret Group and the Holbox Hotel Association.

The Hernández Foundation is best known as the principal caretakers of the Edward James Gardens in Xilitla, but it was founded in 2002 by an entrepreneurial family based in northern Veracruz. Most of their work focuses on the oil-rich Gulf coast, in projects related to the environment and sustainable development for local populations. Flamingos are one of their principal concerns.

The partnership’s efforts have discovered that some birds migrate as far as 5000 km and they documented one 22 year-old individual in 2022, thanks to his identification bands.

Habitat work includes both the monitoring and restoration of feeding and breeding grounds in the four reserves and other areas, especially the water quality in Ría Lagartos because of its importance as a breeding site.

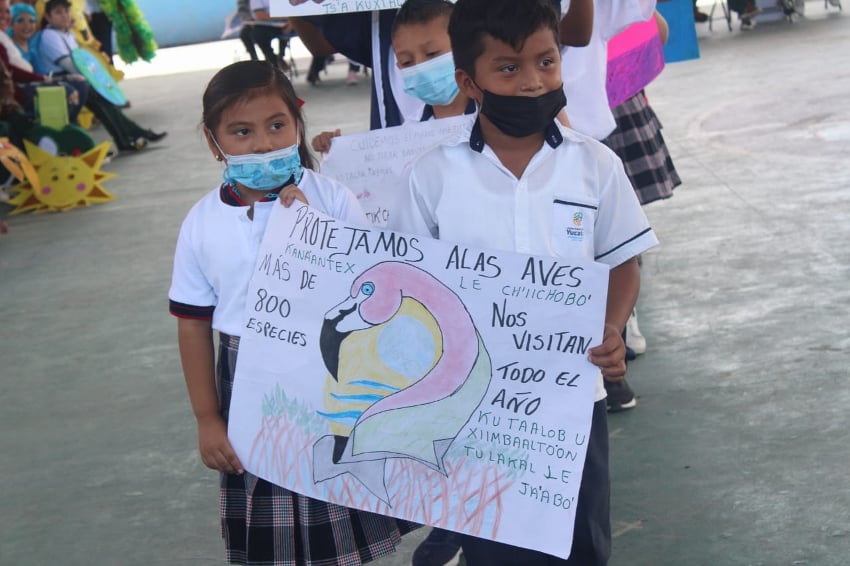

But conservation also means working with local communities. Educational efforts are aimed at both school children and adults to increase awareness of the birds’ importance. It also includes supporting efforts to develop eco-friendly economic initiatives to lessen the need to damage wetlands, and even sterilization of local cats and dogs to reduce predatory pressure on the birds.

Their efforts have paid off. Not only are many of the feeding and breeding grounds in better condition, there is more public support for protecting the birds.

The Foundation’s and government’s efforts are headquartered in Casa Artemia in El Cuyo, which México Desconocido magazine declares a “bird paradise.” It is primarily a scientific research facility, but it also offers ecologically-friendly lodging to visitors through several online booking sites. It also works with local tour operators to offer kayaking, boating and hiking opportunities.

So how does all of this fit in with flamingos in Florida? You might be shocked (I was) to find out that flamingos were wiped out by hunting in the state by the end of the 19th century, and until very recently, all Florida flamingos were captive populations mostly for tourists. They had been absent from the ecosystem for so long that when the first wild ones started showing up in the very beginning of this century, with bands indicating that they were born in Mexico, local authorities thought they were invasive.

But the knowledge gathered in Mexico and other locations proved that these flamingos were simply following their natural migratory instincts, and did indeed belong in Floridian shallows. Authorities have since updated their policies and conservation efforts have begun to increase wild populations in the Everglades and elsewhere. It won’t be easy, however. Florida has development pressures that Mexico’s Yucatán has been able to avoid so far.

Mexico has played an extremely important role in the understanding and appreciation of the flamingo in at least three countries. And with friendly relations with both the United States and Cuba, it is in a unique position to make sure that there are massive flocks of flamingos for the marvel of future generations.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.