One hundred and seventy-six years ago today, at the end of the Mexican-American war, Mexico’s territory became 55% percent smaller and the United States’ territory grew by more than half a million square miles. What are now the states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, and parts of Arizona, Colorado, Oklahoma, Kansas and Wyoming, once Mexican soil, became United States territory.

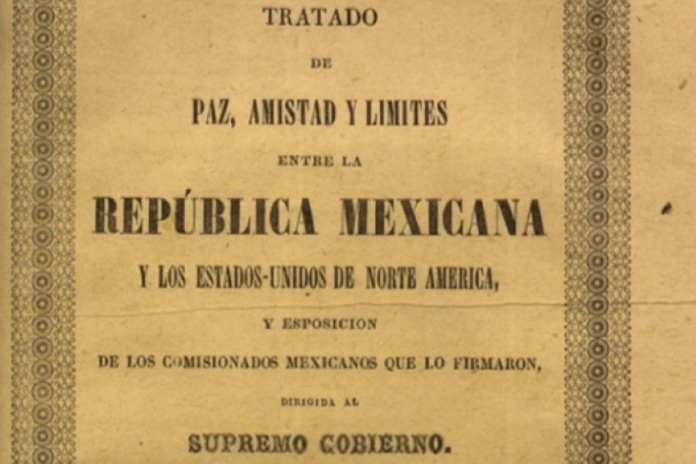

This concession, which forever changed the political, economic and social fate of North America, was stipulated in the terms of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848.

The ramifications of the Treaty

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo put an end to the Mexican-American War. In addition to the enormous land concessions, Mexico received around US $15 million and a pardon of $3.25 million dollars of debt owed to the United States government.

It gave birth to the American West and determined the treatment of those who had been there for hundreds — and in the case of Native Americans, thousands — of years.

Nearly 80,000 Mexican citizens lived in what is now the United States, and the new treaty promised to protect them, at a time when slavery remained legal in the United States.

The treaty stipulated that Mexicans who resided in the territories previously belonging to Mexico were free to stay in their homes or move south to the Mexican Republic if they so wished and could keep their property or sell it without “being subjected to any contribution, tax, or charge.”They were also free to retain their Mexican citizenship or acquire U.S. citizenship, but not both. They had to decide within one year of the treaty.

Now let’s find out how we got there.

It all started with Texas

When Mexico won independence from the Spanish in 1821, much of its northern territory was sparsely populated by a mixture of Mexicans and Native Americans. This land lacked major settlements or development. The Mexican government encouraged people from the United States and other foreigners to settle there, giving them incentives like exemptions from taxes.

In return, the new settlers would become Mexican citizens and speak Spanish, convert to Catholicism, and keep no slaves (as Mexico had gradually abolished slavery after becoming independent). These were promises which many Protestant Anglo-American settlers did not take seriously.

Slavery in particular was a complicated issue, as many settlers were slaveholders who wanted to work around Mexico’s abolition of slavery.

The clash of customs and opposing national interests in the state led to many political and military confrontations,and Anglo colonists revolted against the Mexican government, declaring the independent Republic of Texas. Mexico never recognized the province’s independence, and Texas joining the U.S. as the 28th state in 1845.

Mexican-American war

At the time, the President of the United States was James K. Polk. Polk was a firm believer in “manifest destiny,” an idea — which Hernán Cortés might describe as unoriginal — that the United States had a divinely ordained duty (ordained by God) to expand west across North America. He was determined to take more than Texas.

Polk offered $30 million dollars for California and New Mexico, a proposal that offended Mexico and was rejected immediately. Needless to say, he didn’t handle the rejection well.

Seeking war, Polk sent troops to occupy a disputed area in Texas, which resulted in a clash between Mexican and American troops. Provided with the perfect justification for an attempt to take Mexican land by force, Polk asked Congress for approval to declare war against Mexico, which he received in May of 1846. And so began the invasion known as the Mexican-American war.

Spanning dozens of battles across Mexico, the war lasted 21 months and cost thousands of lives. Although fighting in Northern Mexico continued, the war itself ended when the United States seized Mexico City.

The United States Congress ultimately refused to comply with parts of the Treaty, breaking up land grants where Mexicans lived, resulting in many impoverished communities.

In Mexico, the conflict provided a national identity rooted in animosity towards its neighbor. It also gave birth to the legend of the Niños Héroes, teenage Mexican Army cadets who threw themselves from the walls of Chapultepec Castle clutching the Mexican flag, rather than have the symbol of their country defiled.

- Political figures from the United States like then-congressman Abraham Lincoln, former President John Quincy Adams, and Fredrick Douglass opposed the Mexican-American War. The treat is now seen as a major step toward the U.S. Civil War, some 15 years later.

- The Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty gave way to what is known as “The Gadsen Purchase,” another treaty in which the United States paid Mexico $10 million dollars for a 30,000 square mile portion of land, which later became part of Arizona and New Mexico. This purchase attempted to resolve territorial conflicts that lingered after the war.

North America has been dealing with land disputes since Europe first arrived in the “New World” in the 1500s. While history is often disputed and told from conflicting viewpoints in books, classrooms, and at dinner tables, it is undeniable that its effects are profound. When thinking about the political, foreign, and diplomatic relations between the United States and Mexico, it’s valuable to remember what happened 176 years ago today.

The beginning of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo states the “sincere desire” for both nations to “establish upon a solid basis relations of peace and friendship.” Hopefully, that desire can serve as a guidepost for the two countries almost 200 years later.

Montserrat Castro Gómez is a freelance writer and translator from Querétaro, México.