The event that put the World Fair on the map was London’s Great Exhibition of 1851. Promoted by Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, it was held in a giant glass and iron pavilion — the Crystal Palace — in Hyde Park, London. These early exhibitions changed society. Thousands of working-class people bought excursion tickets on the new railways to visit the show, and in doing so changed the nature of tourism. The big profits in the travel industry no longer came from bringing a few lords and ladies to luxury spas. Rather, it was all about getting thousands of factory workers to come to the seaside for their holidays.

It was World Fairs that gave the first demonstrations of the telephone, flushing toilets and the ice cream cone and it was World Fairs that first inspired the mass production of tourist souvenirs.

Mexico’s first World Fair exhibits

Mexico’s first participation in a World Fair came in 1876. The venue was Philadelphia, and the occasion was the centennial of the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America, which had been signed in that city. There were over nine million visitors, and among the highlights was the chance to see the torch-bearing arm of the Statue of Liberty, the statue being under construction at the time. Only ten years had passed since the execution of Emperor Maximilian, and Mexico was still seen as a backward and unruly country. A Mexican representative to the U.S., Gabriel Mancera, convinced the Mexican government that participation might help repair the country’s tarnished image. However, Mexico lacked experience with such events, and there were insufficient funds to support a major exhibition. The Mexican impact was therefore minimal, with exhibitions in a small area in the “international” building and some minor representation in the art gallery.

Two years later, an international fair was held in Paris, where the task of promoting Mexico was left to private enterprise. Once again, the Mexican exhibition made little impact. The review magazine, Les Merveilles de l’Exposition de 1878, praised the maps of Messrs. Debray and Co. and the onyx marbles of Messrs. Guttierez, but beyond that, they noted, “We see nothing of interest. Hemp, cigarettes, a small quantity of chemical and pharmaceutical products, goat skins, vanilla and mescal brandy, that is the Mexican exhibition.”

The next decade was largely a time of peace and economic progress under the autocratic rule of Porfirio Díaz, with mining and the building of railroads bringing in foreign investment. As the small Mexican elite mixed with foreign businessmen in the office and the sports club, they started to look to the outside world with more interest. This drove Mexico’s return to international exhibitions. In 1884, Mexico was represented at the World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition, a largely forgotten event staged in New Orleans to commemorate the emergence of the post-Civil War American South. The Mexican presence in New Orleans was an expensive enterprise, with Ramón Ibarrola designing a multicoloured steel-and-iron Moorish-style Mexican Pavilion. This can still be seen today, on the Alameda in Santa María la Ribera.

The World Fair of 1889

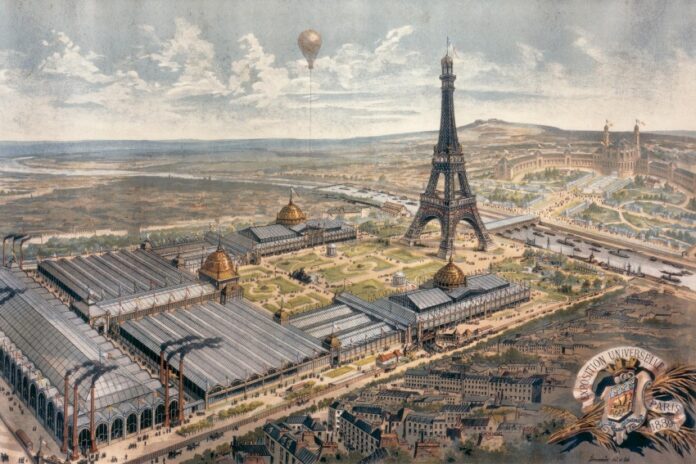

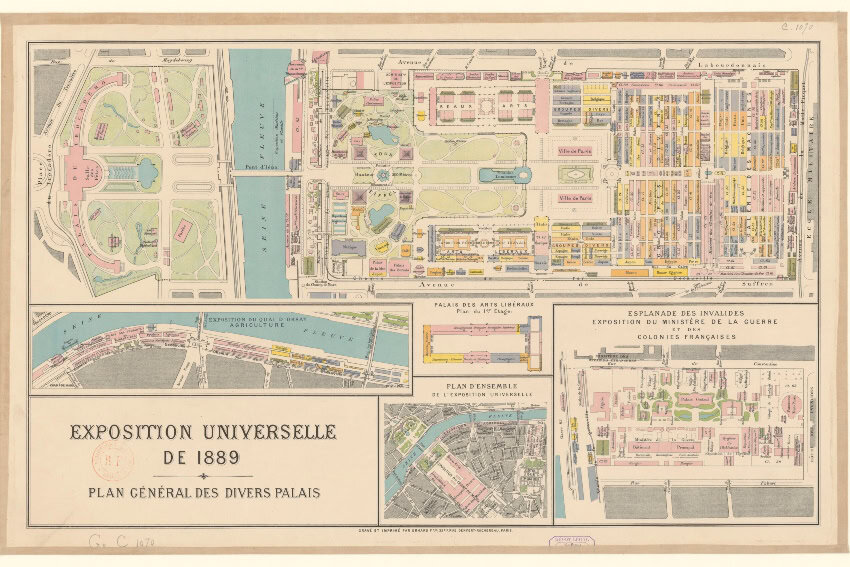

Five years later, in 1889, a world exposition was staged in Paris. Costing 46 million francs, it is considered the greatest fair of the century and has left a legacy that still impacts the host city, for the centerpiece was none other than the 330-meter Eiffel Tower. Intended to be dismantled after twenty years, the tower remains the iconic symbol of the city today. Although eventually successful, the fair was controversial at the time. The theme was the Republican values of the French Revolution, and although nearly a century had passed since the execution of Louis XVI, a number of countries with monarchies did not officially take part. However, thanks to French diplomatic efforts, their absence was barely noticed. The French Empire stepped up to fill the gap, boycotting countries were still presented by individual companies, Thomas Alva Edison brought his new phonograph, Buffalo Bill brought his Wild West Show and Mexico stole the show with their Mexica-inspired pavilion.

There was little to fault the Mexican organization. A central organizing committee was approved, this made up of a team of high-profile representatives from the various ministries. This grand committee appointed teams to oversee the nine groups that would make up the Mexican exhibition. Fully funded by the government, the team departed for Paris with a budget of 5 million francs (then almost 1.5 million pesos), the largest fund of any nation at the exposition.

Mexican participation in the World Fair of 1889

Ramón Fernández, the Minister of Mexico in Paris, was a great supporter of Mexican participation, and work started on the Mexican pavilion. The successful 1884 pavilion in New Orleans had drawn from Mexico’s Spanish culture, which in turn was heavily influenced by Arabic designs. The architectural team for Paris had access to a pre-publication copy of Dr. Peñafiel’s “Monuments of Ancient Mexican Art.” Now, for the first time, there was sufficient knowledge to allow the pavilion to take on a Mexica-like appearance. This temple-like building would cover 2,159 square meters with two side pavilions flanking the main hall, from which an elegant double staircase led to the upper galleries.

Once the project was approved by the Mexican government, negotiations started with the French over the location. A small area had been assigned to the Latin American countries, but this space might have to be shared with the exhibits of some European countries, something Mexico wanted to avoid. After long negotiations, Mexico was granted a rectangular area 70 meters long and 30 meters wide. This was next to Argentina’s exhibit. However, as desired, it was some distance from the European displays.

Mexico’s image portrayed to the world

As the exhibits started to be placed in the pavilion — maps, samples of rocks and minerals, tobacco, hides and skins, building materials, sugars, wines and spirits, plants, flowers and fruits, gold, silver, henequen, coffee, cacao and endless photographs — it started to portray an image of modern Mexico. There was a particularly impressive collection of Mexican textiles, displayed on mannequins that reflected the size and build of the native people of the various Mexican regions. The fact that the Mexican factories producing many of these goods lagged behind Europe and the United States in technology was not hidden, but exploited. It allowed Mexico to be portrayed as an ideal place to invest.

There was also a political side to the exhibition. The Mexican government was anxious to show that it had brought stability to an often turbulent country, and there were photos of new national monuments and buildings, as well as drawings of future projects. Education was an important component of this, and there was a display of educational statistics, issues of major Mexican newspapers and journals, and numerous copies of works from schools.

Perhaps because it was so ambitious, the pavilion wasn’t inaugurated until June 22. However, with the Fair already open, this created a more dramatic spectacle. As the La Marseillaise and the Mexican national anthem were played by the Mexican 101st battalion orchestra, French President Sadi Carnot, flanked by the directors of the exhibition and Mexican dignitaries, climbed the steps of what was called the “Aztec Palace.” At that very moment, the Eiffel Tower was lit up by fireworks, and the light fountains began their display. It was a delayed but perfect start to the show!

How Mexico fared at the World Fair of 1889

By the time the fair closed at the end of October, Mexico had come out with honour. As the Guide Bleu du Figaro et du Petit Journal 1889 summarised, “Mexico has done a great deal, and its exhibition must be ranked among the most remarkable.” It continued, “In the middle of this Street of American Nations, Mexico stands out in a very glorious way for this great country.”

After the success of Paris, we might question why Mexico did not attempt to stage a similar event, if on a smaller scale. There had been proposals in 1878 for a “Mexican-American Fair,” an idea that had resurfaced in 1880. One problem was that Mexico, for all its progress, was still a developing nation. Creating a picture of a vibrant Mexico in a pavilion in Paris or the U.S. was one thing. Inviting the world to come to a city that had its share of problems was quite another.

The story of Mexico at World Fairs continues into modern times. Dubai hosted the most recent global event, Expo 2020, where Mexico, with its cloth-wrapped pavilion and visual efforts, again put on an impressive show. It was a continuation of the legacy that started in Paris 131 years before.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.