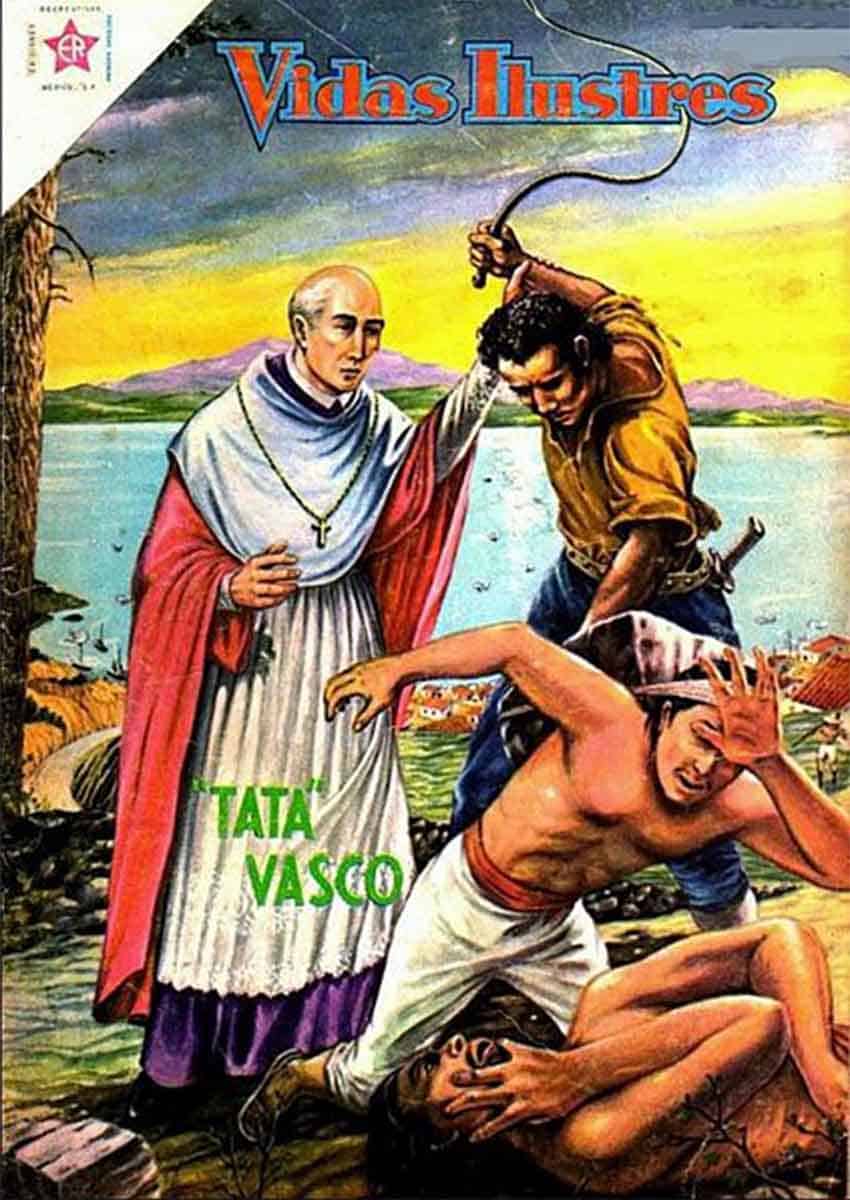

If you spend any time in the Lake Pátzcuaro area, you will undoubtedly come across the name Vasco de Quiroga. Almost venerated here, he carries the Indigenous title of tata, literally “father,” but the word is infused with meaning from the area’s spiritual and political past.

In statue form, Quiroga still watches over the main square of Pátzcuaro. His influence can be seen throughout the city, giving it a much different feel than other central Mexican colonial communities. His work is likely responsible for conserving Purépecha culture and identity here, although that was not his goal.

Quiroga was born in Ávila, Spain, to a well-connected family. Traditionally, his birth is thought to be the year 1470, although this has been disputed. He was not educated as a priest but rather in canon law. He was named a oidor, or judge, of the second Real Audiencia of Mexico, the court that governed New Spain in the years immediately following the conquest of Tenochtitlán.

The First Audiencia was a disaster both according to the Indigenous peoples and the Spanish, and so Quiroga’s mission upon arrival in 1531 was to salvage the situation in favor of the latter.

Quiroga was an idealist for his period, heavily influenced by Thomas More’s book “Utopia.” This word has a more secular meaning today, but in Quiroga’s time, the idea of a utopia was to create a social order that reflected heaven as much as possible.

Quiroga translated More’s ideas into “hospital-towns,” where “hospital” referred to safe areas for the Indigenous people to gather, reorganizing them quasi-communally in order to teach them Christianity and Spanish culture.

Quiroga’s work began in Santa Fe, then in a small town in the Valley of Mexico, using his own money. But his destiny was located in the lands of the former Purépecha Empire.

After the destruction of Tenochtitlán and with their communities already suffering from smallpox, Indigenous authorities in the major Purépecha city of Tzintzuntzan surrendered to Spain in hopes of better treatment.

They were sorely disappointed. The abuses of the Real Audiencia’s leader, Nuño de Guzmán, and company were so bad that many of those who didn’t choose outright rebellion fled for the mountains.

Quiroga came in 1533 to assess the situation, eventually sending Guzmán and others back to Spain in chains. That out of the way, Quiroga set about repeating what he did in Santa Fe but on a grander scale.

Quiroga enticed the Indigenous back into life under Spanish rule, starting in Santa Fe de la Laguna and Santa Fe del Río. The focus was on (Spanish) order, religious observance, work, education and “practical arts,” with just about every aspect of life regimented.

The Second Audiencia gave way to the appointment of New Spain’s first viceroy in 1535. Quiroga was offered the newly-created job of Archbishop of Michoacán. He was not a priest, but that was quickly remedied, and he continued his work under ecclesiastical authority.

He moved the diocese to Pátzcuaro in 1537, founding a cathedral and the Seminary of San Nicolás (today the Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo). The seminary was open to both Spanish and Indigenous applicants.

Quiroga’s work was instrumental in the development of many central Michoacán towns, and his reach extended into Salamanca (Guanajuato) and even Guadalajara. But he had another legacy: Michoacán’s culture of handcrafts — one of the most important in Mexico.

The Purépecha were already accomplished artisans, more advanced in metalworking than even the Aztecs. When Quiroga organized his hospital-towns, he assigned many towns to a specific craft in order to avoid competition and to promote trade among them.

Many of these towns maintain their assigned craft today: copper working in Santa Clara de Cobre, musical instruments in Paracho and different styles of pottery in the towns of Tzintzuntzan, Patamban and Capula, just to name a few.

The best that Michoacán has to offer can be seen at Day of the Dead festivities in Pátzcuaro in November and the Palm Sunday Market in Uruapan.

Except for an eight-year period between 1546 and 1554 (due to Church business), Quiroga remained in Michoacán for the rest of his life. His aim was to extend his concept of utopia all over New Spain. But his ideas never gained widespread acceptance outside the Lake Pátzcuaro region, because many Spanish thought they were unworkable or would cut into their ability to profit.

Indigenous people today are particularly fond of Quiroga’s legacy because he worked against the worst of Spanish abuse. In his most famous piece of writing, “Information on Rights” (“Información en Derecho”), from 1535, he argues against the Crown’s reneging on a promise not to enslave the conquered Indigenous — albeit unsuccessfully.

There was even a movement to have Quiroga canonized starting in 1997, but ended in 2004.

But Quiroga was no saint. Many of his ideas would be considered cruel and authoritarian today, not to mention racist. Like other priests, he worked to destroy the old beliefs (rather unsuccessfully in his lifetime) and social order.

Despite working against slavery, he did have slaves — who were released upon his death. He did not support preserving or documenting Indigenous languages and cultures and even tried to get the Inquisition to ban a Christian treatise published in Purépecha.

It’s necessary to frame Quiroga’s work in the context of his times in order to understand why he remains important today.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.