The political cartoon has left an indelible mark on the political satire of Mexico. Beginning in the 1820s, it became a powerful tool for political critique and social commentary. Deeply rooted in Mexico’s freedom of expression, by 1877, political cartoons had become an important part of Mexican politics and culture. Caricaturists used finely honed weapons — their drawing instruments and their talent — to provoke ridicule and induce laughter.

The roots of the political cartoon in Mexico

The War of Independence saw the flowering of journalism in Mexico after a long period of colonial censorship, with dozens of pro-independence newspapers appearing in the first years of independence struggle. In the early independence period, publications took advantage of the newly-enshrined freedom of the press and kept up their activism, taking sides in the divide between centralists and federalists.

The stage was set. But the political cartoon would not have been possible without a specific technology: lithography, the printmaking technique invented in 1796. In September 1825, days after Mexico celebrated its first anniversary as a republic, Italian lithographers Claudio Linati and Gaspar Franchini arrived in Veracruz to set up the country’s first lithography press.

It was El Iris, the newspaper that Linati established in Mexico City, that published the first political cartoon ever printed in the country. “La Tiranía” (Tyranny), published in the April 15, 1826 issue of El Iris, shows a tyrant on a throne accompanied by a priest and a demon waving a bloody axe while another demon burns liberal newspapers of the time. In a sign of things to come for political cartoonists, El Iris ran for only 40 issues and Linati was forced to leave Mexico for his political agitation.

The Golden Age of the political cartoon

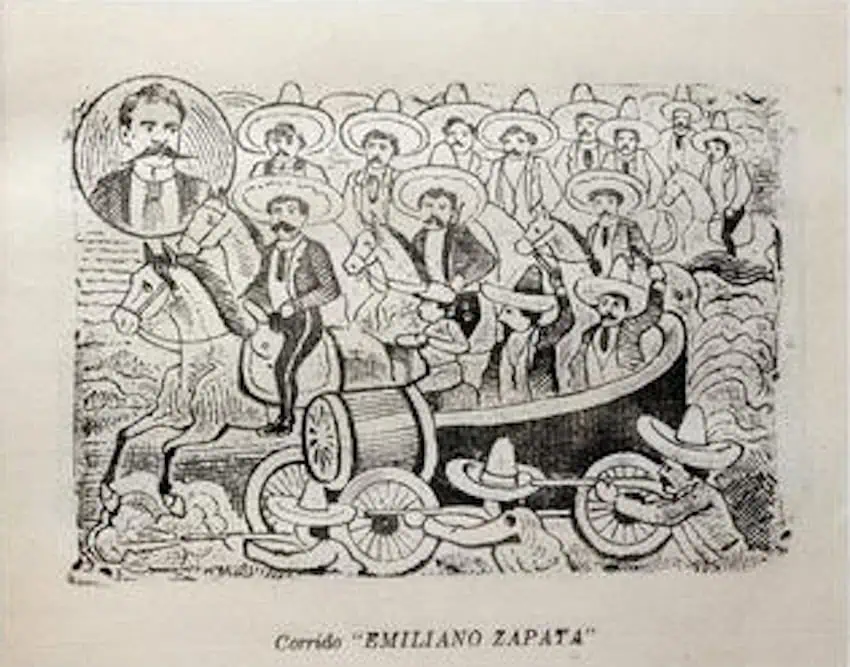

The political cartoon exploded as lithography became more widespread, and cartoonists weighed in on all sides of every major event of Mexico’s turbulent first decades, from the Mexican-American War to the Second Empire to the liberal Reform. It was the Porfiriato, however — the 34-year rule of President Porfirio Díaz — that ushered in one of the most productive periods in the history of Mexican cartooning.

When the weekly La Mosca appeared in 1877, it made its intent crystal clear with the headline: “Impertinent newspaper with a sharp sting that will itch Porfirio and his people.” Díaz immediately shut them down. After this development, some cartoonists stopped signing their caricatures. In 1879 the popular weekly El Tranchete launched a sharp criticism of the Díaz regime, causing the newspaper to be suspended.

The weekly El Hijo del Ahuizote, founded in 1885, was a leader in political satire. In 1902, the paper was taken over by the brothers Enrique and Ricardo Flores Magón, who led it to play an important role in generating opposition to the Díaz government. The weekly’s strength was its ability to reach the country’s people with easy-to-understand, simple and direct language. As a result of their success, they expanded their readership, reaching the masses and strengthening the gestating Mexican Revolution. Eventually, the paper’s staff was persecuted and jailed by Díaz for the crime of offenses against public officials. The Díaz government also decided to imprison all of their collaborators in Mexico City’s notorious Belen prison, including typographers and lithographers.

Jesús Martinez Carreon, one of the most significant and combative cartoonists against the Díaz regime, collaborated with the weekly for ten years until it closed. He was one of several cartoonists imprisoned in Belen prison, where he contracted typhus and died in 1906. The Flores Magón brothers, unable to publish their writings, went into exile in the United States and would eventually stage several uprisings that played a role in inciting the Mexican Revolution in 1910.

José Guadalupe Posada changes cartooning

In 1908, the working-class-oriented paper El Diablito Rojo appeared to take El Hijo del Ahuizote’s place, featuring anti-Díaz cartoons by cartoonist José Guadalupe Posada. Posada, known as the pioneer of printmaking and the artist who created La Calavera Catrina, was a prolific illustrator and printmaker. La Catrina became symbolic of Mexican culture and the Day of the Dead. His satirical and politically charged illustrations were very recognizable due to the unmistakable signature cadavers that Posada used to satirize and criticize the politicians and public figures of the time.

The original print of La Calavera Catrina has an etching of a female skeletal figure wearing an elaborate French hat decorated with ostrich feathers but not wearing clothing. To the Mexican women, he seems to be saying “You have nothing but you are still wearing a fancy hat.” He is also criticizing Porfirio Díaz who was known for his French affectations – powdering his face white and donning European clothing. Posada often used skulls and cadavers to mock politicians and the upper class, sending a message of equality: For all your preening and prancing around, we are all equal when we die.

The 20th century is considered the Golden Age of the political cartoon, and satirical cartoons were critical to the success of the Mexican Revolution. Despite facing censorship and backlash, the cartoonists continued to challenge power and speak truth to those who hold that power. Political cartooning is built into Mexico’s history and continues its commitment to push for change by fostering social consciousness.

Political cartooning continued following the end of the Mexican Revolution. Porfirio Díaz was exiled and Francisco Madero became president, but satirical cartoons were here to stay. The caricaturists even took swipes at the popular new president, poking fun at Madero’s belief in Spiritism and his insistence that he spoke with the spirits of the dead, including Benito Juárez. Political satire poked fun at every president that followed.

Political cartoons in the 21st century

Political cartooning continued to thrive in the last half of the 20th century and into the 21st, in print and digital formats. Among the best known living cartoonists — often called moneros — are José Hernández, Rafael “Rapé” Pineda and Rafael “El Fisgón” Barajas.

The political cartoon holds a special place in the hearts of Mexicans as a powerful instrument for social commentary and freedom of expression. This cultural tradition continues its mission today of challenging authority and encouraging dialogue and public discourse.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive, researcher, writer and editor. She has been writing professionally for 35 years. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance writing. She can be reached at AuthorSherylLosser@gmail.