Since his 2016 campaign for U.S. president, Donald Trump’s rhetoric on immigrants has gotten harsher and uglier. Having deported 1.5 million people during his first administration, the American president-elect campaigned on the promise to initiate mass deportations. Many people think this is far-fetched, insisting that it would be impossible to round up and deport millions of people — but it has happened before, as Herbert Hoover decided to launch the deportations of every Mexican in the United States.

In 1931, the United States was in the throes of the Great Depression. Millions were out of work and families were suffering. President Herbert Hoover searched for solutions to turn the economy around, but his approach was piecemeal. He decided on what he felt would be a popular program by white Americans: the mass deportation of Mexican Americans, freeing up their jobs.

“American jobs for real Americans”

“Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s,” the first major work of research on Hoover’s mass deportations, was published by Californian historians Francisco Balderrama and Raymond Rodriguez in 1995. “Decade of Betrayal,” as well as research conducted by Balderrama and Rodriguez in collaboration with California State Senator Joseph Dunn and his staff in the early 2000s, remains an important source of knowledge as to what happened during this campaign of deportation. Dunn’s research has found that 1.8 million people were deported during the Depression.

Hoover’s administration called it a National Program of “American jobs for real Americans” — the implication being that only whites were real Americans. The Republican’s government worked to convince the public that deportation was for the best, a humanitarian act of helping Mexicans rejoin their families in Mexico. The truth is that it was brutal and inhumane. The repatriation program was carried out by Hoover’s Secretary of Labor, William Doak.

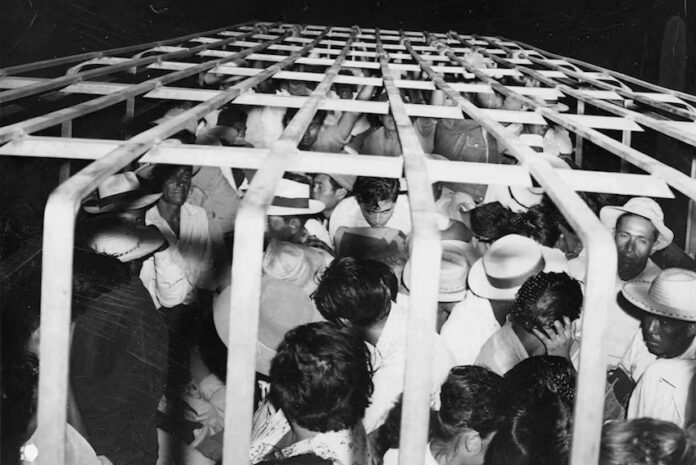

Close to two million Mexicans and Mexican Americans — thousands at a time — were rounded up without due process, loaded onto cramped trains, transported to central Mexico and dropped off in rural areas with only the clothes on their backs. Photographic evidence shows the crowds dropped off at railroad stations awaiting their deportation. They included women, children and many who had been born in the United States, were U.S. citizens and didn’t speak Spanish. Many Mexican nationals deported were also U.S. permanent residents. No one was safe if they ‘looked Mexican.’

As part of the program, Doak also appealed to local officials to pass laws preventing Mexicans from holding government jobs, even if they were U.S. citizens. Many major U.S. corporations — among them U.S. Steel, Ford and Southern Pacific Railroad — supported the government’s actions, firing anyone of Mexican descent. The fired workers, Francisco Balderrama told NPR in 2015, were told they “would be better off in Mexico with their own people.”

With the mantra “a Mexican is a Mexican,” work records and government rolls were scoured to search for names that sounded Mexican.

The round-up begins

Nationwide — in the South, North and as far away as Alaska — Mexicans and Mexican Americans were rounded up wherever they congregated: markets, hospitals, social clubs, plazas and public parks. Mexican Americans were being blamed for the bad economy and were filled with fear, not knowing when they or their families might be deported.

California was a primary target due to the number of Mexicans and Mexican Americans who lived in the state. According to historian Francisco Balderrama, Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors member H. M. Blaine proclaimed that “the majority of the Mexicans in the Los Angeles Colonia were either on relief or were public charges.” Political support for the repatriation program was not only found in California. Congressman Martin Dies, a Texas Democrat, wrote in the Chicago Herald-Examiner that the “large alien population is the basic cause of unemployment”.

The most famous round-up happened in downtown Los Angeles’ Placita Olvera in 1931. On a Sunday afternoon on Feb. 26, a time when many Mexicans enjoy a day with family at the local park, a large group of armed plainclothes officers entered La Placita Park and began rounding up everyone who looked Mexican. Dozens of flatbed trucks and police vehicles circled the park, and officers were posted to prevent anyone from fleeing.

More than 400 people were lined up and asked to show proof of their legal entry to the United States. The crowd panicked. Very few people carried documentation with them to spend a day in the park with their families. The children had no idea what they were supposed to produce. Those without proper documentation were loaded onto the flatbed trucks and taken to the city’s main railroad station where they were ordered onto chartered trains and taken to rural parts of Mexico.

There were however some political leaders who fought back. In 2024, Joseph Dunn told the Washington Post that The Los Angeles City Council told the County Board of Supervisors numerous times in memos to stop their illegal deportations. “This isn’t about constitutional validity,” the supervisors responded. “It’s about the color of their skin.”

The raids were vicious, targeting people using public resources. Francisco Balderrama found cases of Los Angeles hospitals having orderlies gather up Mexicans, put them on stretchers, load them on trucks and transport them to the border, where they were left to die.

Officials justified their actions by saying deportation would free up jobs for non-Mexican Americans and accused Mexicans of overwhelming welfare rolls, draining them of money needed for others. Hoover gained public support by doubling down on his message that deporting Mexicans would free up money for “real Americans” in their time of economic need. The U.S. president continued to describe the deportations as merely repatriating Mexicans to their birthplace, but documentation shows that 60 percent of the deportees were U.S. citizens. Hoover told the public that this would “keep families together” when in reality that was never the intention and deportations in fact tore families apart.

The tragedy continues

Many families left in central Mexico had young children who were traumatized by the experience. They were ostracized in school because they didn’t speak Spanish. The United States was the only country they knew. They had always had indoor plumbing and schools, and suffered from a lack of medical care where they found themselves.

Mexicans still in the United States who had not yet been deported found there was no one to help them. With so many deportations, anyone working on public assistance was gone. Trade unions favored mass deportation because they felt it would free up jobs for their white members.

The racist deportations did not stop with Hoover. After Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in January 1933, he never officially revoked the “American jobs for real Americans” program, which was primarily being carried out by local governments. By the beginning of World War II, Mexican labor was back in demand — especially for low-paying agricultural work — and jobs left behind by the men sent to war needed to be filled. The program eventually just faded away and was forgotten.

1954 saw another wave of deportations by the government of Dwight Eisenhower in the form of the so-called “Operation Wetback,” the largest mass deportation in U.S. history, which added military-style tactics to Hoover’s old strategy of leaving people deep in central Mexico. Eisenhower’s government claimed that over a million people were deported or self-deported.

California apologizes, the United States doesn’t

Pressured by State Senator Joseph Dunn, California finally passed the Apology Act in 2005, apologizing for the Mexican Repatriation Program. In front of La Plaza de Culturas y Artes, a memorial was dedicated in 2012, inscribed with an apology to the hundreds of thousands of U.S. citizens who were illegally deported from California during the Great Depression.

Many Mexicans don’t want to talk about the deportations because there of the shame attached to it. But generations were destroyed by the brutality and cruelty of “repatriation.” To this day, Dunn told The Atlantic in 2017, the U.S. Congress refuses to issue a formal apology because the immigration issue is “too volatile.” Everyone wants to sweep the shameful deportations and xenophobia of the 1930s under the rug in the hope that the American people will not take the time to learn more about it. Unfortunately, eliminating that piece of history may mean we have to relive it again in 2025.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive, researcher, writer and editor. She has been writing professionally for 35 years. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance writing. She can be reached at AuthorSherylLosser@gmail.