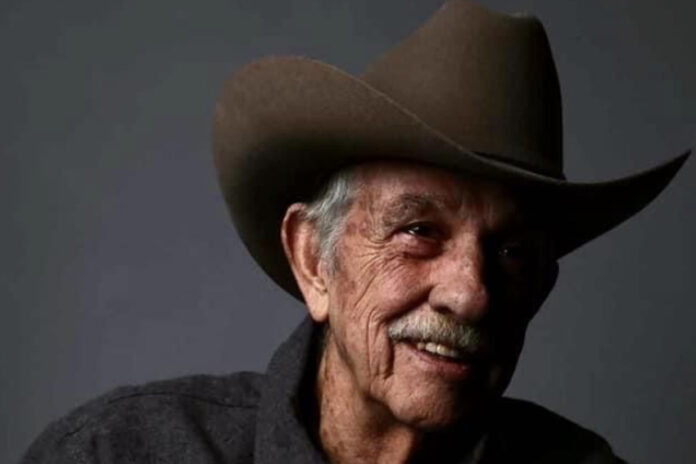

I had the recent honor and pleasure of chatting with Don Patterson in San Miguel de Allende about his fascinating career in Mesoamerican archaeology, which spanned three decades from the 1970s to the early 2000s. Over the course of his career, Patterson worked on more than 150 archaeological sites from Honduras to northern Mexico. He is an expert in archaeological illustration, recording innumerable discoveries of pre-Hispanic artworks by photographing them and then creating stunning drawings.

Patterson arrived in Mexico in 1970 at the age of 27, inspired by the opportunity to study with the esteemed sculptor Lothar Kestenbaum at the Instituto Allende in San Miguel de Allende. Kestenbaum gave Patterson his first book about the Maya, which sparked a life-long fascination and course of study.

At the Instituto Allende, Patterson earned a Masters in Fine Arts. He also gained a wife — less than a year after arriving in San Miguel, Patterson married the beautiful Marisela García de la Soto. They have one daughter, Jessica Patterson. After graduating, he was offered a job teaching painting and life drawing at the Instituto Allende, while fascinating discoveries of pre-Hispanic artifacts in the local area drew him inexorably to archaeological work.

Discovering the throne of Bird Jaguar III, Lord of Yaxchilan

The Yaxchilan project was one of his favorites because of the site’s storied history — and because of the incredible discovery he made there.

“I can recall with great clarity the days excavating and the subsequent nights drawing and photographing the throne of Bird Jaguar III,” said Patterson. “In the world of the classic Maya, Bird Jaguar was the Lord of Yaxchilan during the eighth century after Christ. Roberto [García Moll, the site director] gave me the opportunity to excavate the northwest exterior corner of Structure No. 7. Known as “Templo Rojo de la Rivera,“ it was famous because Teobert Maler spent nights in this building during his renowned explorations of the late 1890s.”

Patterson continued. “As my brush began to reveal the undulating surface along the sides of the first of two large stones beneath the soil, my excitement rose. At moments like these, controlling your impulse to attack the dirt like a dog looking for a bone is very difficult. The next hour seemed like an eternity before enough dirt was removed around the edges and the full-figure glyphs were exposed. I was ecstatic.”

“At that time there were few places apart from Copan, Honduras, and Quirigua, Guatemala, where full-figured glyphs had been found on carved stone. When the complete throne was freed and I saw the glyph for Bird Jaguar, I thought there would never be another moment in my life such as this. But of course I was wrong.”

A new golden age in Mexican archaeology

For centuries, the looting of archaeological sites — in Mexico and throughout the world — had been out of control. Then in 1973, an important law was passed in Mexico. As Patterson explained, this critical legislation “gave the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) decisive power in the determination of the national patrimony. Those who looted and trafficked in [objects from archaeological sites] were now subject to very stringent laws and severe punishments.” Importantly, the legislation “gave INAH a mandate to conserve, protect, investigate and diffuse the archaeological patrimony of Mexico.”

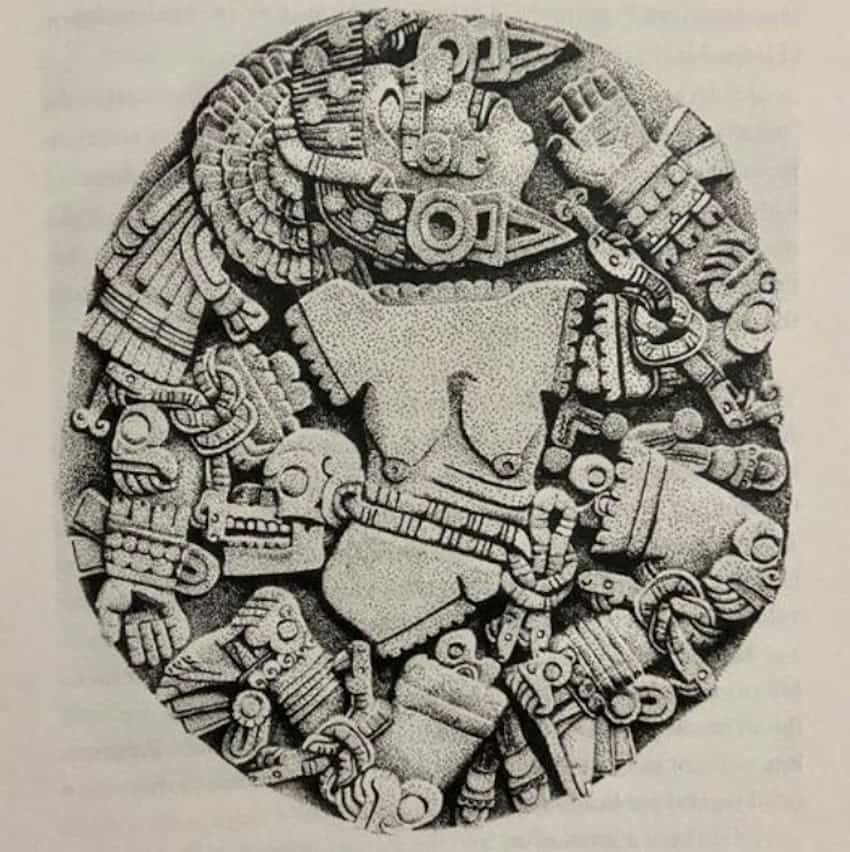

And it worked. “Compared to many other countries in Latin America, Mexico virtually stopped the massive looting that had been taking place for centuries… Moreover, during this period there was a resurgence of pride in the national patrimony unheard of since the golden epoch of Manual Gamío, Alfonso Caso and Jose Vasconcélos, one consequence being the swelling up of nationalistic fervor. Of course, this was augmented within and outside INAH by the discovery of the huge Coyolxāuhqui stone and the subsequent excavations at the Templo Mayor.”

Joining INAH to work on the Templo Mayor

Patterson knew he’d received a big break in 1978 when the National Institute of Anthropology and History’s highly respected general director, Professor Gaston García Cantú, referred him for a job at the Templo Mayor, where his use of a “camera lucida” technique enabled him to be highly efficient and effective in documenting the many exciting discoveries being made at the site. Only two gringos worked for INAH at the time.

“I was extremely lucky that my first paying job for INAH, in 1978, was at the Templo Mayor… it was an exciting place to be working. Every day something new was brought to light in the excavations. Academics, kings, presidents, congressmen, ambassadors and movie stars from around the world came to see the Coyolxāuhqui, whose dismembered body, weighing eight tons, lay at the bottom of the stairs to the temple of Huitzilopochtli.”

Monte Alban and Chichén Itzá

“Monte Alban was the first project I coordinated for the INAH general director’s office. During that time, we documented the carved monuments of Monte Alban, Dianzu, and Yagul, Oaxaca. After a few more years of labor, the work at Monte Alban evolved into a reference book, ‘Los Monumentos Escultóricos de Monte Albán,’ in Spanish and German.”

Patterson loves that his daughter, Jessica, has memories of playing among the ruins of Chichén Itzá as a child while her dad worked there on a six-year project. Some of his other fondest memories are of the talented and dedicated people he worked with.

For example, Patterson spoke highly of Don Eugenio May, an experienced leader of the excavation team at Chichén Itzá, who, “having worked the better part of his life at the site, knew the location of every mound in the 22 square kilometers that encompassed the great center of Chichén. All 64 Mayans I hired, from three villages around Chichén Itzá, treated Don Eugenio with great respect and referred to him as El Abuelo.”

While identifying chultuns (artificial storage units dug into the bedrock) at Chichén Itzá, Patterson felt like he and his crew were facing tests from the lords of Xibalba, the underworld depicted in the classic Maya text the Popol Vuh: in one day, the first chultun they explored contained a rattlesnake, the second a wasps’ nest, and the third dozens of bats! A few days later they also found a “three-meter-long boa appropriately coiled in the mouth of one of the stone serpent heads in the main plaza.”

Coming home to San Miguel: Río Laja and the Cañada de la Virgen project

Also during this time, Patterson’s team began a settlement pattern study along the central portion of the Río Laja in Mexico’s Bajío region, which led to fascinating results. As Patterson explained, “Wherever we found a present-day rural community, or ranchería, there was sure to be at least one pre-Hispanic settlement nearby. In other words, the present-day farmers are utilizing the same alluvial soils that their predecessors had a thousand years earlier! As well, nearly every ranchería has an 18th century chapel, while a few were built around the structure of colonial haciendas. This was convenient and facilitated our documentation of the colonial heritage as well, since we could accomplish it simultaneously with the pre-Hispanic.”

Once their survey was completed, they began to analyze the data. “The density of the sites with standing architecture in this northern frontier valley of Mesoamerica was nearly one every ten square kilometers. We presumed that the site density would surely be greater as one traveled south toward the heartland of Mesoamerica. If this was true, then Mesoamerica contained potentially more archaeological sites than previously suggested.”

With these compelling results, Patterson’s team made a strong case for the creation of a national registry of sites, a National Archaeological Atlas.

Patterson’s last project was in his own proverbial backyard, at the Cañada de la Virgen archaeological site near San Miguel de Allende. “For four and a half years, for 48 hours per week, we worked at the site in an unbroken chain of field seasons” from December 1995 through January 2000.

After the Cañada de la Virgen project, Patterson worked as the Director of Ecology for the municipality of San Miguel.

In closing, Patterson explained a guiding principle of archaeology: Beyond economic limitations, “an important reason for not excavating any structure completely is the professional obligation to preserve as much data as possible for future research. With proper funding and the rapidity with which technology and other sciences like physics, chemistry, biology and botany were becoming involved in archaeological projects, it was more important than ever to maintain this time-honored ethic.”

Journey to Xibalba: A Life in Archaeology

The legacy of this feisty gringo’s contribution to Mesoamerican archaeology is impressive. The collection of books that he either wrote, edited, or was extensively cited in fills several bookshelves. I can personally confirm that Patterson’s memoir, “Journey to Xibalba: A Life in Archaeology,” is a fantastic read, and he would want me to also encourage you, dear reader, to study the Popol Vuh in order to hear from the classic Maya in their own words and perhaps even embark on your own “journey to Xibalba.”

Don Patterson passed away on June 2 in San Miguel de Allende.

Based in San Miguel de Allende, Ann Marie Jackson is a writer and NGO leader who previously worked for the U.S. Department of State. Her award-winning novel “The Broken Hummingbird,” which is set in San Miguel de Allende, came out in October 2023. Ann Marie can be reached through her website, annmariejacksonauthor.com.