Some Mexican churches built by Indigenous artisans hide secrets of pre-Columbian mythology in their architecture and design.

South of Guadalajara and north of Lake Chapala stand a string of venerable old churches which bear witness to the naïveté of the Franciscans who had them built and the cleverness of their Indigenous builders and decorators.

In the 16th century, the Spaniards settled remnants of Indigenous peoples from all over Mexico in a corridor stretching from Santa Anita at the southwest corner of today’s greater Guadalajara to Lake Cajititlán, 12 kilometers north of Lake Chapala.

Native peoples displaced by Spaniards

Living in this corridor were Purépechas and Cocas, who were previously accustomed to fighting with each other; there were Náhuas, transported from the center of Mexico and Caxcanes from Zacatecas; and then there were the Tlaxcaltecas who had been allied to the Spaniards and were considered conquerors rather than conquered. They were allowed to ride horses and carry weapons and enjoyed benefits the other Indigenous did not.

A Republic of Indigenous Peoples

“So, what happened,” says archaeologist Francisco Sánchez, who has been studying the area and the period for years, “was that they formed a kind of Republic of Indigenous Peoples, consisting of “pueblitos,” each of which was known as an “altepetl.” This concept had already existed in pre-Columbian Mexico and was resurrected in what I call ‘The Tlajomulco Corridor’ around the end of the 17th century.”

Secret messages from native church builders

Sánchez discovered that the churches and chapels in this area were being used not only as places of Christian worship but also displayed what he calls “ideographic information,” visible in their facades and sometimes in the very architecture of the buildings.

“When those Indigenous people looked at a church,” says Sánchez, “they didn’t just see what the priests were presenting. Instead, they were getting secret messages. They were seeing concepts that went back to pre-Hispanic times.”

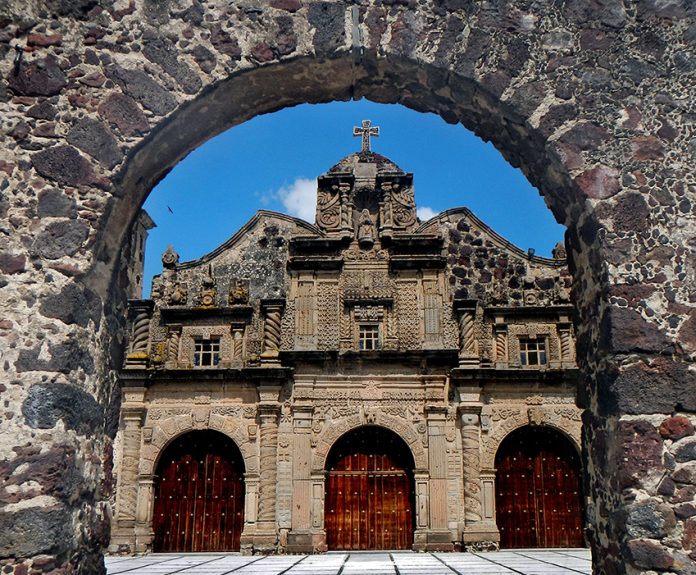

An example of this, Sánchez added, is the Chapel of Santa Anita’s facade, built between 1740 and 1795.

This church is named after Saint Anne, the grandmother of Jesus, but locally, it is best known for an image of the Virgen de la Candelaria (the Virgin Holding a Candle), a friar brought to the church from Spain around 1782. The image, it was claimed, could cure the infirm and gained great popularity.

The grandmother of Jesus or the goddess Toci?

All of this was noted by the Indigenous artisans who were sculpting the facade of the Santa Anita Chapel. These artisans knew very well that the pre-Columbian goddess famed for curing the sick was Toci, whose name means “nuestra abuela,” our grandmother.

Toci, says Sánchez, is represented by snakes in pre-Columbian mythology, “and here, on the facade of Santa Anita chapel, we see snakes all over the place.”

For example, Sánchez points to the projections beneath two statues on either side of the door. “Each is the head of a Mexican horned pit viper, much venerated in ancient times. The eyes of the snake are disguised as the heads of cherubs, and spirals on both sides represent its horns. At the bottom, a double spiral represents its forked tongue.”

So, at this chapel, a Spaniard sees the grandmother of Jesus and a virgin who cures illnesses, but, comments Sánchez, “any Indigenous person who looks at this facade says: ‘This is the house of Toci,’ and when they walk into this building they are not walking into the sanctuary of the Virgin of the Candelaria, they are entering the house of Toci.”

Tlaloc, the rain god

Another example Sánchez brought up was the nearby church of Santa Cruz de las Flores: “The silhouette of this building is in the shape of a hawk, a pre-Hispanic symbol of water, and among the decorations on the wall, you may find one that looks a lot like Tlaloc, the rain god.”

This church is also well decorated with symbols of flowers because the town was initially called Xochitlán, the Place of the Flowers. On one of the oldest sections of the church’s often repaired facade, three bules (gourds), traditional vessels for carrying water, can be seen.

“If you find this interesting,” commented Sánchez, “you should also look at the church in San Juan Evangelista, located on the shore of Lake Cajititlán: the entire building is shaped like Tlaloc!”

Anything goes “out in the boonies”

I asked Francisco Sánchez whether the priests of these churches had an inkling of what their parishioners saw in them.

He replied that in the Tlajomulco Corridor, they may not have suspected what was going on. Near Mexico City, he explained, “priests were armed with detailed descriptions of everything the native people held sacred. They made efforts to prevent ‘pagan’ symbolism or practices creeping into Catholic rites. Out in the ‘boonies’ (read western Mexico), the Spaniards thought the natives were disorganized and bereft of culture, so the Franciscans were allowed to develop their own style of evangelization. St. John, for example, was accepted by the Indians as a sort of new, improved Tlaloc, and ancient rites related to rain were incorporated into Catholic ceremonies.

“In this multi-ethnic republic,” said Sánchez, “the Indigenous people are not passive at all; they are actively involved in constructing their own reality. Here, we have something beyond a ‘conquista.’ These people still have a cosmovision of their own… and they are transforming it into something new.”

A thousand-year-old pyramid

If you visit some of the churches and chapels mentioned above, you may also want to climb to the top of a thousand-year-old pyramid in San Agustín, just 2.5 kilometers southwest of the Chapel of Santa Anita.

La Pirámide de la Loma (the pyramid of the hill), warns Francisco Sánchez, was “restored” by local people who didn’t bother to consult an archaeologist. Nevertheless, what you experience at the top of the pyramid is impressive because you have a 360-degree view from this point, allowing you to discover that you are standing smack in the middle of a great circle of mountains.

“This is truly a special place,” you say to yourself, and even if the pyramid was restored all wrong, that message from its original builders still comes through loud and strong.

To visit the duplicitous churches and the incorrectly restored pyramid mentioned above, ask Google Maps to take you to:

- Santa Anita Chapel: “GHX5+GC Santa Anita, Jalisco”

- Santa Cruz Chapel: “FFJR+CC Santa Cruz de las Flores, Jalisco”

- San Juan Evangelista Church: “CM3P+MC San Juan Evangelista, Jalisco”

- Pyramid of La Loma: “GGPQ+PF San Agustin, Jalisco”

You don’t need to be an archaeologist to discover the hidden messages in these 17th-century churches and chapels.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.