Shortly after arriving in Mexico in 1938, André Breton, the French father of Surrealism, had proclaimed the country “…the surrealist place par excellence.” Years later, Salvador Dalí would reinforce this notion saying, “In no way will I return to … a country that is more surreal than my paintings.”

Today, the word “surreal” is still used to describe Mexico, often by us foreigners to describe aspects of its culture that are both awe-inspiring and inscrutable. But the European concept of the Surreal was not initially accepted by the Mexican elite.

Breton and the Surrealists wanted to turn away from rationalist Western thought to re embrace more “marvelous” ideas, which they found in part in (sub)cultures relatively unaffected by European Renaissance heritage.

Not surprisingly, Mexico — with its pyramids, feathered serpents, shape-shifting naguals, voladores hanging from tall poles and dancing calaca skeletons — caught their attention.

Breton wrote extensively about Mexico. It was superficial, but it brought other artists here, such as Wolfgang Paalen and Gordon Onslow Ford, who went well beyond Breton in their understanding of Mexico’s indigenous cultures.

Surrealism dominated Europe starting in the 1920s, but when European artists came to Mexico, they ran up against the other major artistic movement of the time – Muralism.

The work of Diego Rivera and others not only dominated a very nationalistic Mexico at the time but had international acclaim as well.

Artists from the two movements shared a number of common interests: a romanticization of Mexico’s indigenous past and present, Marxist and anti-fascist politics and an artistic focus on the figurative. How each approached these interests, however, reveals significantly different worldviews.

But the Muralists were busy creating a new Mexican identity for a post-Revolution nation, whereas after World War I in Europe, the Surrealists were not particularly interested in nationalism. And as Marxism split into factions in the Soviet Union and elsewhere, Muralists and Surrealists found themselves supporting different factions.

Lastly, Muralists’ figurative work was more realistic, looking to portray history and indigenous heritage. The Surrealists were looking to portray dreams and other images that exist only in the mind.

In the 1930s and 1940s, many Surrealists and other European artists and intellectuals found themselves in Mexico as the Spanish Civil War and yet another world war raged. They were welcomed because of their politics and education, but they were still foreign refugees.

All of these issues led to Surrealism being marginalized in Mexico for decades until the 1950s, when Muralism’s dominance began to significantly wane. Surrealist artists such as Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Kati Horna would form semi-separate communities in places like the Roma and Condesa neighborhoods of Mexico City.

It is notable that Mexico’s most prominent “classic” Surrealist artists are women, whose work would not receive national recognition until the 1950s or later. One possible reason is that male Surrealists such as Paalen, Onslow Ford and later Alan Glass would abandon Surrealism and even Mexico to develop their careers.

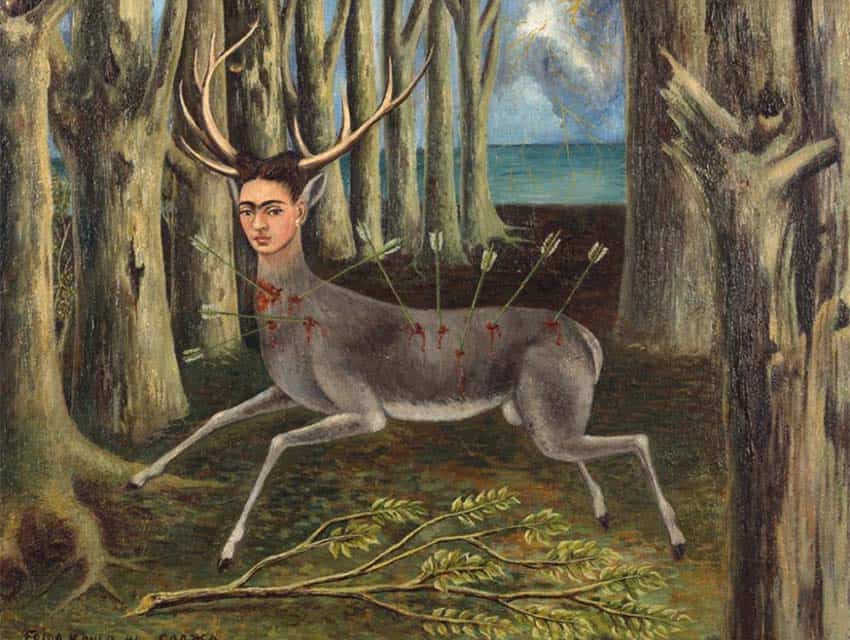

But what about Frida Kahlo? In Mexico, she is generally not recognized as a Surrealist artist despite the many obvious similarities. She was recognized as such by Breton, who promoted her work in Europe, but eventually Kahlo would disavow Surrealism over issues of nationalism and communist ideology. Most Mexican writing about her work “respects” her insistence that her work is completely her own.

However, it would be wrong to say that Surrealism has had no effect on Mexican art. Many artists from the two movements formed professional and personal ties. Mexico’s artists and writers borrowed from Surrealists. Surrealist influence has been attributed to work by Juan Soriano, María Izquierdo and even Rufino Tamayo.

And the Surrealists and other European artists set the stage for post-Muralism.

The Breakaway Generation (Generación de la Ruptura), a movement from approximately 1950-1970, essentially was a rebellion against the nationalism and aesthetic restrictions of Muralism. Many Breakaway artists had European teachers influenced by Surrealism.

Overall, the Surrealists’ presence reminded Mexico during the height of its insular Muralism era that the outside world still existed — and now these younger artists wanted to explore. Unfortunately for Surrealism, by the time the Ruptura gained traction in the 1950s and 1960s, the art world had shifted from dreams to abstract art.

Surrealists also were responsible for sparking the beginning of internationalizing Mexican art, a process that continues to this day.

With the exception of politically charged work, such as that of Los Grupos or Neo-Mexicanismo, avant-garde art produced in Mexico is nearly indistinguishable from that produced in other Western countries.

This has been strengthened by the influx of globally-minded artists that have migrated to the country since the mid-century for both cultural and economic reasons.

But surrealism never completely died in Mexico. Interestingly enough, there are a number of indigenous artists who are creating canvases and more, drawing upon their native cultures, including the spiritual. French art critic Serge Fauchereau has written that the “marvelous” that the Surrealists adored appeared long before and after the movement.

Supernatural concepts find their way into the work of Jorge Domínguez Cruz of Veracruz, who draws from indigenous Huastec culture. Oaxacan Filogonio Naxin combines elements of his Mazatec culture, in particular naguals, with modern print/graffiti sensibilities to create what he calls “social surrealism.”

The word “surrealist” may turn out to be a way to make the work of at least some indigenous artists more relatable to other cultures. If this is the case, the original Surrealists’ obsession with indigenous Mexico may not have been entirely misplaced.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.