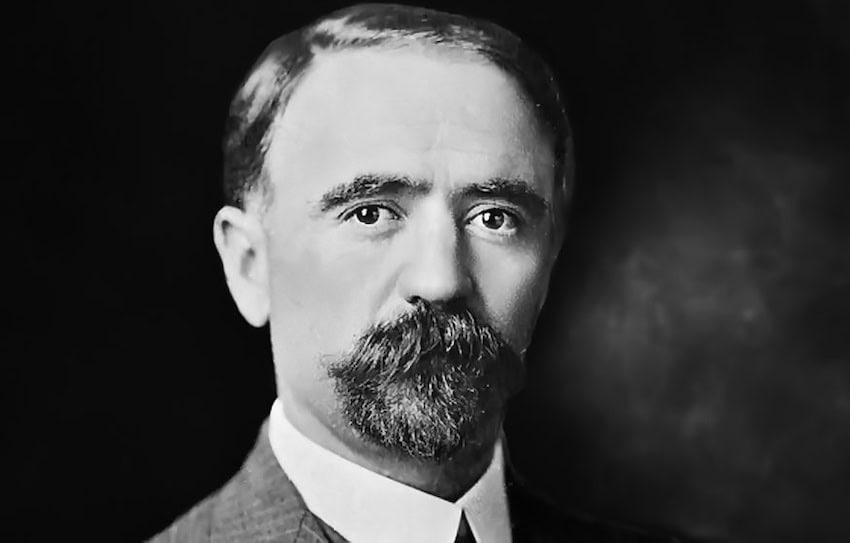

Francisco I. Madero was seen by many in Mexico as an odd duck. The northern landowner was a well-known Spiritist who spoke publicly about his experiences speaking to ghosts during seances — including President Benito Juárez — and possessing the skill of automatic writing. In 1910, Porfirio Díaz, who had ruled Mexico for 40 years through sham elections, announced his intention to leave power, and Madero became the Anti-Reelectionist Party’s candidate for president. Fearing that Madero could beat his chosen candidate, Díaz jailed him, igniting the Mexican Revolution.

Diaz’s regime fell in May of 1911, and elections were called for October. Madero won handily, bringing a group of loyalists with him to office.

Surprisingly, besides his wife Sara Pérez Romero and brother Gustavo, Madero counted two Germans as trusted confidantes. Even more surprisingly, both men were spies.

The German agents

Madero’s two Germans were Arnold Krumm-Heller and Felix Sommerfeld. Like Madero, both men were Spiritists. Krumm-Heller, who was highly regarded in esoteric circles, left Germany in 1876 for Mexico but returned to Europe in 1907 to study medicine. In 1910, he returned to Mexico and became Madero’s personal doctor.

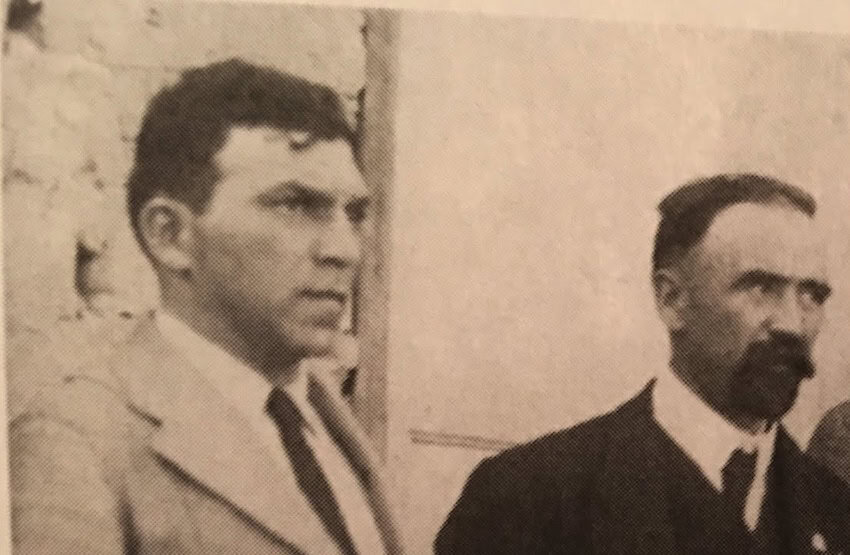

Sommerfeld, born in Germany in 1879, had already had an exciting life by the time he reached Mexico: he joined the U.S. Army, went absent without leave at the outbreak of the Spanish-American War and had fought against the Boxer rebels in China. He first met Madero in Chihuahua while working as an informant for German naval intelligence under the cover of being a reporter for the Associated Press. His cover allowed him to send regular intelligence reports to Germany without suspicion. While in Chihuahua, Sommerfeld learned of Madero’s revolutionary activities and made contact with the anti-reelectionist.

Sommerfeld and Madero

Madero and Sommerfeld developed a close relationship, and Sommerfeld was seen as his closest confidante. Madero’s brother and trusted advisor Gustavo appointed Sommerfeld head of the Mexican Secret Service. Krumm-Heller joined him at the secret service. In that role, Sommerfeld was always at Madero’s side, his sharp eagle eyes on the lookout for signs of trouble. He was still a German spy and from this new position he began building a spy network in the United States consisting of Mexican Americans, Mexican expatriates and other German spies.

When Madero won the presidency in 1911, Sommerfeld accompanied him to Mexico City. Other than photos, the only glimpse we have into their relationship comes from Sommerfeld’s 1912 appearance before the United States Senate, where he testified that “President Madero is the best friend I have in this world.” When asked to elaborate, he replied, “we became very close friends.” The two men had many traits in common. Not only were both men spiritists, but neither man drank, gambled or smoked.

While serving Madero, Sommerfeld befriended a valuable contact in the United States, Washington, DC lawyer and lobbyist Sherburne G. Hopkins. Hopkins’ clients included the richest and most influential industrialists and oil tycoons in the United States, and he was introduced to the revolutionary cause by Madero’s brother Gustavo. Sommerfeld became Hopkins’ gatekeeper for any businessman trying to gain access to Madero.

The Ten Tragic Days

Madero’s government was weak and faced revolts by poor peasants who felt betrayed by his failure to implement land reform. Dissatisfied with his leadership, conservative generals plotted to overthrow Madero. In February 1913, they launched the coup d’etat known as the Ten Tragic Days. Madero was assassinated, and General Victoriano Huerta seized the presidency.

Arnold Krumm-Heller, Madero’s doctor, was arrested by Huerta but was freed by the intervention of the German government.

Under the protection of the German ambassador, Sommerfeld fled to Washington, D.C., where he joined the rebel movement assembled to overthrow President Huerta. Venustiano Carranza, governor of Coahuila, also opposed Huerta and created the Constitutionalist Army. Carranza sent Sommerfeld to El Paso and San Antonio to acquire arms for the revolutionaries, making the German the liaison between the U.S. government and Carranza.

Sommerfeld becomes invaluable

Huerta was defeated in July 1914, and the revolutionary factions came together at the Convention of Aguascalientes to write a new national constitution. They were unable to do so, and the revolutionaries split between Carranza’s moderate Constitutionalists and the radical Conventionalists led by Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata. A new bloody phase of the revolution had begun.

That year, Sommerfeld began working with Pancho Villa, acquiring American weapons for Villa’s troops U.S. officials were aware of him: when prominent journalist Ambrose Bierce, who was embedded in Villa’s army mysteriously disappeared, the U.S. Army chief of staff contacted Sommerfeld to investigate the matter.

In 1914, Sommerfeld also spent a brief stint in New York as a naval attache to German naval officer Karl Boy-Ed helping Germany formulate its war strategy vis-à-vis the United States. While working with him, Sommerfeld informed Germany he could provoke a war between the U.S. and Mexico. The next year, Sommerfeld rejoined Villa’s efforts, funneling a large number of arms — around US $7 million in today’s value — to the Villista troops.

In March 1916, Villa and a small group of his men used those weapons to attack the city of Columbus, New Mexico, prompting the United States to send General John J. Pershing on an ultimately unsuccessful mission to capture Villa. Sommerfeld became the prime suspect in planning the attack, but his involvement has never been proven.

U.S. authorities pretty much left Sommerfeld alone because he was helpful to them, but briefly had him interned in 1918 at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia as an enemy alien although he was released in 1919.

Sommerfeld was known to have returned to Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s, but there are no detailed accounts of what he did while he was in the country. His trail disappeared until 1942 when he signed a draft registration card listing an address in New York City and his age as 63. There is no trace of him afterward.

The mysterious and elusive Felix Sommerfeld played a vital role in the Mexican Revolution. No other foreigner amassed as much power as he did. As head of Mexican security, he created an enormous spy network, used that network to gather intelligence for Germany but also to terrorize and decimate Madero’s enemies. Sommerfeld’s connections and actions are complicated. Did he operate as a spy for both Germany and Mexico? Was he also a spy for the United States? A double agent? A triple agent? No one knows the full story of Felix Sommerfeld – his personal life and motivations remain an enigma.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive, researcher, writer and editor. She has been writing professionally for 35 years. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance writing. She can be reached at AuthorSherylLosser@gmail.