In late June — Friday, June 27, to be exact — I was walking in the historic center of Mexico City when I stopped at a sidewalk kiosk that sells newspapers and a myriad of other miscellaneous items.

The selection of daily newspapers, neatly arranged on a metal frame and held in place with clothespins, had caught my eye. The front pages of several papers featured stories about the government intervention at three Mexican financial institutions accused of money laundering by United States authorities.

But one tabloid newspaper had a very different headline extending across the top of its front page:

“MIAUUU” — the word in Spanish for “meow,” with a couple of extra vowels at the end for emphasis.

“They called him the cat and they found him dead next to a stall in Azcapo[tzalco],” read the deck (subheading) on the cover of the Mexico City edition of the Metro newspaper, published by Grupo Reforma.

To the left of a photograph of the man who was found dead in the northern borough of Azcapotzalco was another, very different image — one of a bikini-clad woman with the following text superimposed on her backside: “Porn star looks for boyfriend online.”

This kind of journalism is the bread and butter of Mexican tabloid newspapers such as Metro and El Gráfico, both of which are popular, if not highbrow, publications and cover news that is often not reported by the mainstream press.

A new genre is born

“On Sunday, November 17, 1889, one week after the attack on General Ramón Corona, El Mercurio Occidental astonished the readers of Guadalajara with a striking front page: alongside a portrait of the assassin Primitivo Ron, they printed what appeared to be the imprint of his hand in red ink, next to stains of the same color that resembled blood. People were left stunned at the sight of that cover. … Thus la nota roja was born in the country.”

So wrote historian Ricardo Cruz García in the magazine Relatos e historias en México.

“Unlike in other countries, where it is mainly known as yellow journalism or police reporting, in Mexico the local editorial tradition prevailed and the name nota roja — in honor of that front page [in 1889] — took strong root, [used] to identify information related to crimes, violence, and tragedies that is presented in a sensationalist manner,” Cruz wrote.

Similarly, the journalist Isai Monterrubio wrote in Gaceta UNAM, a publication of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, that the front cover of the Nov. 17, 1889, edition of El Mercurio Occidental “marked the starting point for one of the most emblematic genres of graphic journalism in our country: la nota roja, a record of horror.”

Thus, la nota roja has a rich history in Mexico dating back more than 135 years, with numerous publications — both newspapers and magazines — focusing on this kind of journalism throughout the 20th century and beyond.

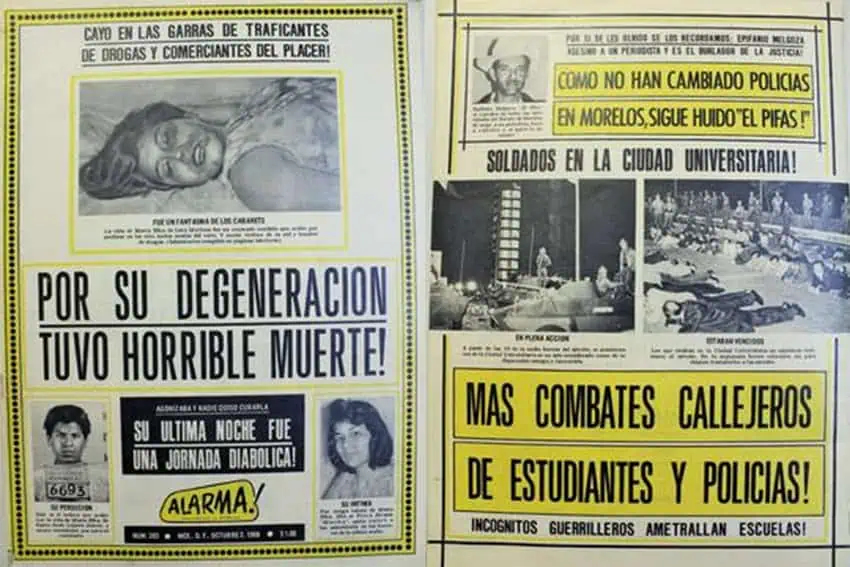

Alarma! informed — and shocked — Mexicans for almost 50 years

One of the most popular, and most shocking, nota roja publications was Alarma!, a magazine launched in the early 1960s, and relaunched as El Nuevo Alarma! in 1991 after a five-year hiatus.

“The magazine really took off in 1964 with the story of Las Poquianchis, who were three women who ran an infamous prostitution ring in Guanajuato,” Miguel Ángel Rodríguez Vázquez, the now-deceased former editor of El Nuevo Alarma!, told VICE in late 2007.

“They were accused of committing 28 homicides. All of their victims were young girls who worked for them as prostitutes, and all of their bodies were found buried in Las Poquianchis’s backyard.”

Rodríguez told VICE that the 1985 earthquake in Mexico City was also a “huge story” for Alarma!, but soon after the “huge boost” in sales generated by the extensive reporting on the devastating natural disaster, the publication “was shut down by the government,” ostensibly due to “things like not printing the appropriate ‘adult only’ warnings on the cover or selling the magazine in plastic bags.”

The second incarnation of the magazine, as El Nuevo Alarma!, lasted more than two decades until 2014. Shortly after the publication of the final edition, Rodríguez died of a heart attack in a Mexico City Metro station, and consequently, as the magazine Chilango reported, became a nota roja story himself.

“People are interested in the kind of thing we publish,” he told VICE in 2007.

“I don’t think it’s an illness, I think it’s curiosity. People like to see what we’re made of inside. We have millions of photographs of cadavers with their intestines hanging out. … It’s really strange, and lots of people love to see that. Plus, if we don’t publish enough dead bodies in an issue, we get emails telling us that we were too conservative,” Rodríguez said.

Enrique Metinides, ‘the legendary master of la nota roja‘

While thousands of people have contributed to the vast archives of nota roja journalism in Mexico, few, if any, of those contributors achieved the national and international prominence of Enrique Metinides, a photographer who started taking pictures of corpses when he was still a boy.

Born in Mexico City to Greek parents in 1934, Metinides was gifted a camera by his father when he was nine or ten and at age 12 took a photograph that was published on the front page of the newspaper La Prensa, where he became an apprentice photographer.

“El Niño” (The Boy), as Metinides was nicknamed in his early working days, went on to work for numerous nota roja publications over a five-decade career, including Alarma!

In a 2007 interview with VICE, Metinides, who passed away at the age of 88 in 2022, said that “the year after I started taking pictures, my dad opened a restaurant and the local cops used to go there for lunch every day.”

“I got to know a lot of them, and they started taking me to the station to take pictures of the people they arrested and the corpses they would pick up,” he said.

“… I really wanted to be a crime reporter at that age, and I used to collect crime stories from the press, from all around the world. … I started taking pictures all over the city,” Metinides said.

“… I worked for 50 years as a crime photographer. … In Mexico City there’s always been a lot of accidents and a lot of deaths,” he said.

Many of Metinides’ photos have an arresting power — they draw viewers in and make it hard to look away, even though their subject matter is often confronting.

One of his most famous images is that of a woman who was hit by a car and killed on Mexico City’s Chapultepec Avenue in 1979. The photo of the almost serene-looking woman, her head tilted between two poles, is shocking, yes, but also mesmerizing in its own way.

“Enrique Metinides was a very different photographer, … his style was extraordinary,” Trisha Ziff, a filmmaker who made the 2015 documentary “The Man Who Saw Too Much” about Metinides, wrote in the newspaper El Universal shortly after his death.

“… Metinides didn’t just take photos. He was also a witness of difficult events — accidents, crashes, violence in the city,” she wrote.

“… If his work is considered art, it’s because he made very different photographs to those we see among the nota roja photos today. Metinides had a different vision: blood almost never appears in his images, and he uses the moment to capture the whole story,” Ziff wrote.

“… Metinides had a lot of international recognition and received many prizes, including the Espejo de Luz, in 1997, the most important recognition of photographers’ work in Mexico,” she wrote.

View this post on Instagram

The headline of an obituary published in the Milenio newspaper in 2022 read: “Enrique Metinides, goodbye to the legendary master of la nota roja.”

“That niño, who was born on February 12, 1934 and who instead of playing with a ball entertained himself with his German Braun camera, passed away on May 10 at the age of 88 in his Mexico City, which he literally knew from the inside out, in its morgues and in its tragedies, which he portrayed with the dignity that art provides,” the obituary began.

“In a certain sense, the beauty with which he photographed the dead was his way of paying posthumous homage.”

‘Someone once called us raptors,’ but ‘we are human beings’

Understandably, nota roja journalism is not to everyone’s taste — and many people would probably argue that it shouldn’t be to anyone’s taste.

Unsurprisingly, those responsible for writing the stories and taking the often gruesome photographs that fill the pages of nota roja publications have faced criticism for their work.

“We have been told many times that we are insensitive,” Luis Manuel Acevedo, a veteran nota roja photojournalist, told UNAM Gaceta.

“Someone once called us raptors. People say those kinds of things about us; we are not like that, we are human beings,” he said.

According to Nelson Arteaga, a sociologist who has extensively researched issues related to violence, la nota roja provides “another narrative about violence in the country.”

He compared the journalism genre to other “forms of expression,” such as cinema, music and literature, all of which allow “the construction of narratives” about violence.

While it’s graphic, gruesome, sexist, sensationalist and salacious, there can be no denying the enduring popularity of la nota roja in Mexico.

Hundreds of thousands of copies of nota roja newspapers are sold in Mexico every day. A newspaper vendor in Mexico City’s downtown told me he sells far more copies of such newspapers than mainstream publications such as El Universal and Milenio.

“In the end, [la nota roja] has a wide audience because violence crystallized into images communicates something to the public,” Arteaga told UNAM Gaceta.

“What I think would be wrong is if these kinds of magazines didn’t exist, because it would be like trying to hide something that’s there,” he said.

In the newspaper El Economista, journalist José Soto Galindo wrote in 2020:

“Scandal and sensationalism are gasoline for an audience with a pyromaniac instinct and a lighter in their hands. What we call yellow journalism is the result of a market ready to consume stories overflowing with morbidity. And it is a thermometer of the level of violence and barbarity that a society is willing to endure.”

The enduring popularity of nota roja journalism in Mexico is also a product — and representation — of the nation’s distinctive cultural intimacy with death.

Octavio Paz, the only Mexican who has won the Nobel Prize in Literature, wrote in his book “The Labyrinth of Solitude” that while death for a resident of New York, Paris or London is a word that is never spoken “because it burns the lips,” a Mexican, in contrast, “visits her often, mocks her, caresses her, sleeps with her, celebrates her.”

“She is one of his favorite playthings and his most permanent love.”

What will you find in a nota roja newspaper today?

In addition to stories about violent crime and accidents, and pictures of naked women, nota roja newspapers such as El Gráfico and Metro publish crosswords, cartoons, classifieds, horoscopes, sports news, jokes and agony aunt-style columns, among other recurring features.

In the copy of El Gráfico I picked up in late June, one of the questions asked of “sexual consultancy” columnist Cecilia Rosillo was this: Does one’s pubic hair fall out as one ages?

“I’m truly intrigued,” the reader said.

Nota roja newspapers are also known for their ingenious — albeit sometimes unseemly — headlines.

Personally speaking, a couple of the most memorable headlines over the past decade or so have been “Ya es zombi” (She’s a zombie now), published on the front page of Metro after the 2018 death of The Cranberries singer Dolores O’Riordan, and “Tiembla Cabrón” (Shook like a motherfucker), also in Metro, after the powerful earthquake that shook southern and central Mexico on Sept. 7, 2017.

For those of you who are unfamiliar with the genre, and are interested in reading a few archetypal nota roja stories, here are translations of three articles from the June 27 copies of Metro and El Gráfico that I picked up in downtown Mexico City.

He uses up his last life

El Nahual dies at a market stall in the Pro Hogar neighborhood where he prowled around for 40 years

Mexico City – The man who died was called Víctor and he was well-known among the residents of the Pro Hogar neighborhood in the Azcapotzalco neighborhood.

However, only a few people knew his name. Almost everyone knew him as El Gato (The Cat) or El Nahual because they believed he had several lives.

Some said he was about 60, although his gray hair and the wrinkles on his face made him look older.

They say he was from Hidalgo, but he arrived in the neighborhood about 40 years ago and lived in the street since then.

“He wasn’t a bad person, he was doing well and he was active, but his problem was that he started taking drugs. At one point we gave him up for dead because he disappeared, but he suddenly came back about two years ago,” a man recalled.

Three months ago, he started having health problems and they worsened to the point that he couldn’t walk. When Thursday dawned he was stretched out on the corner of Street 12 and Street 15, where a watch salesman sets up his stall.

The salesman recognized him and tried to wake him up, but Víctor didn’t respond and he requested help. It wasn’t until 9 a.m. that police from the La Raza Sector and paramedics confirmed that his last life was gone.

Later, specialists from the Mexico City Attorney General’s Office arrived to begin investigations and remove the body.

– Metro

DiDi … ceased

The motorcyclist went out to pick up an order and was hit by a drunk driver

After leaving a fast-food establishment in the Azcapotzalco borough, a motorcycle deliveryman was hit by an SUV. The DiDi worker died, while police arrested the woman who was driving while intoxicated.

The day before yesterday, before the restaurant’s closing time, the deliveryman arrived at the business in the San Salvador Xochimanca neighborhood to pick up an order. After nine at night, he left the parking lot and headed toward Eje 3 Norte, Camarones Avenue.

But after leaving the location, he was hit by a speeding SUV. The woman at the steering wheel of the Jeep was unable to brake and ended up running over the deliveryman who was riding a low-powered motorbike.

The impact sent the body of the motorcyclist toward the road. Although witnesses stopped to help the man, he died before the paramedics arrived.

WASTED. The woman remained in the SUV until Azcapotzalco police arrived. After listening to her say what happened, the agents took her to the prosecutor’s office.

Witnesses said she was driving in an intoxicated state and was speeding. But it will be investigations that determine if it was alcohol that caused the accident.

The body of the DiDi deliveryman was taken to the morgue of the prosecutor’s office, where it is hoped it will be collected by relatives. Until now, the body hasn’t been identified by his family.

– El Gráfico

Eaten alive

She flaunts her outfit to go get tacos and the criticism pours in

The ex-XXX star, Aída Cortés, visited Mexico, where she didn’t miss out on the opportunity to be gluttonous with tacos. But she wore a very eye-catching outfit, which caused her to be eaten alive with criticism.

The Colombian, who managed to earn up to 120,000 dollars a month (a little more than 2 million Mexican pesos) with her explicit content, decided to turn her life around and dedicate herself to singing.

So she came to Mexico to promote her album. During her stay, Cortés uploaded a video where she is seen in a black corset, stockings and thong that left little to the imagination.

“My outfit to go out to eat tacos in Polanco, Mexico,” wrote Aída, but rather than positive comments, criticism pointing to her outfit appeared on her social media.

“Your outfit is very cute, but it wasn’t the right place to dress like that. You should have put on a casual outfit. It was a family place, not a brothel!” wrote an internet user.

Another said: “Change your life, but respect starts with your attire. It looks like you’re still doing the same thing.”

“You’re free to dress how you want, but in a family place … it’s not very appropriate,” others complained.

– El Gráfico

By Mexico News Daily chief staff writer Peter Davies (peter.davies@mexiconewsdaily.com)