I’m a sucker for a good cantina. I’m also a big fan of Porfirian architecture. Mexico City, to my delight, is a hotbed of those eye-catching façades blending French, neoclassical, and Mexican design elements. So when my date invited me to dinner at the new Gran Cantina Filomeno, an optimal mix, I all but ran there in my kitten heels. Obviously, I was elevating my look — and my height — for this elegant outing.

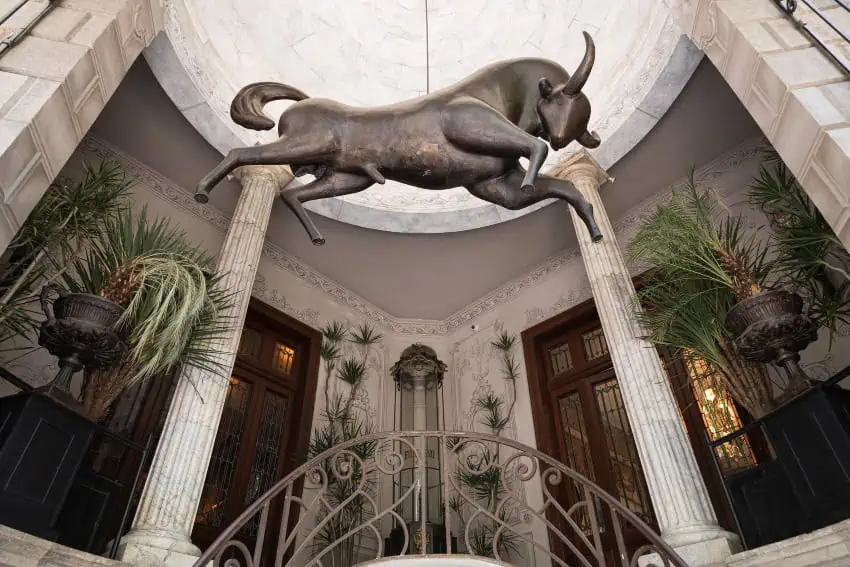

We arrived together at the double marble staircase encased by an iron-wrought rotunda, crowned by a bronze bull suspended in mid-air. What my date didn’t know was that as I ascended the grand entrance, I imagined for a brief minute that I was an aristocratic lady of a bygone Mexico, donning an elegant Belle Époque gown. A welcoming hostess guided us around a wooden bar into a lively dining room with high ceilings clad in dangling ivy. With each step, I delved deeper into Mexico’s storied pre-Revolutionary past, thanks to an abundance of 19th-century artworks that include Victorian furniture, original stained-glass windows and ornate crystal chandeliers.

We slipped into carved wooden seats as she handed us each a bound menu with the letter F inscribed in gold. I thumbed through the various pages of Mexican specialties before stopping on a short blurb of the cantina’s history. Wow, I thought, this place isn’t a cantina, it’s a living museum.

And that’s when I decided to write an article about it.

The wild journey of a Mexico City mansion

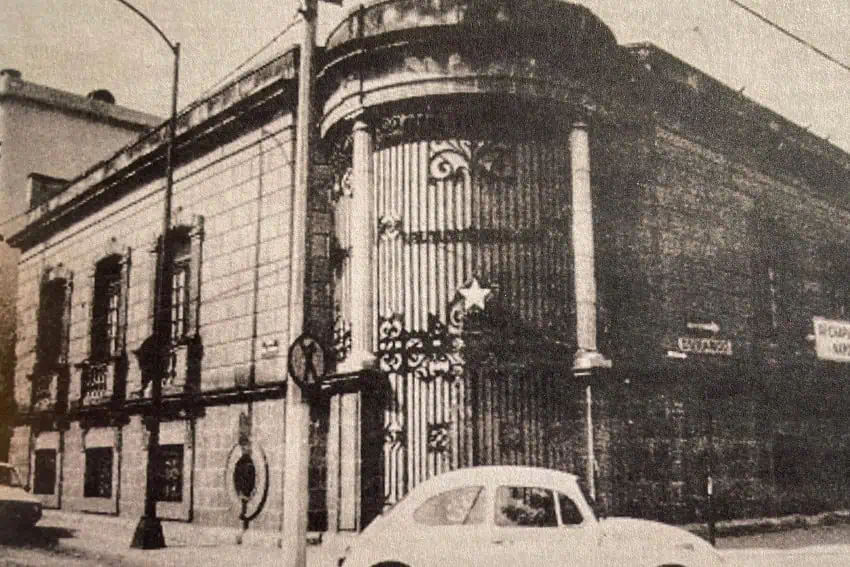

From a millionaire’s mansion to a refuge for Spanish exiles, a girls’ boarding school to a famous art gallery, Rio de Janeiro 54 has lived a full Mexico City life.

The mansion-turned-restaurant’s origins can be traced back to the early 1900s. That’s when Daniel Ruiz Benítez, architect and builder, oversaw its construction as a single-family home on the southeast corner of Parque Rio de Janeiro. Its sophisticated style satisfied the design preferences of Mexico City’s elite of the time, many of whom rose to prominence during the then recently ended Porfirio Díaz regime, and who heavily favored French and Neoclassical architecture.

In the late 1930s, during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas, the private mansion transformed into Casa de España, becoming a refuge for Spanish intellectual exiles fleeing Franco’s dictatorship. The exile community soon became El Colegio de México, where refugees joined Mexican scholars in advanced humanities and social sciences research. Some of these residents would become household names. Alfonso Reyes, for example, served as the college’s first president. Nobel Prize-winning poet Octavio Paz had an office on the ground floor, and notable scholars like Daniel Cosío Villegas and José Gaos also worked there. Even avant-garde filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky lived in the annex next door.

By the mid-20th century, Rio de Janeiro 54 went from housing Mexico’s intellectual elite to becoming a Catholic boarding school for girls. For decades, it remained a female-only residence until the 1980s brought another dramatic transformation.

From art gallery to restaurant

For the next 30 years, the mansion housed contemporary artwork as the renowned OMR Gallery, founded by Patricia Ortiz Monasterio and Jaime Riestra. The gallery became one of Latin America’s most influential contemporary art spaces, helping establish Roma Norte as Mexico City’s arts district. Where Octavio Paz once pondered poetry, cutting-edge artists like Gabriel Rico and Jose Dávila now displayed their work.

OMR Gallery moved to Calle Córdoba in 2015, and that’s when this building’s latest, and perhaps most theatrical, chapter began.

The Filomeno fantasy

The cantina’s transformation started with a novel. In 2010, Daniel Liebsohn — one of Mexico’s leading antiquarians and art collectors — published “Filomeno,” chronicling the adventures of a handsome charro living in the final years of the Porfiriato era. Liebsohn, together with partners Santiago García Galván and George Diamandopoulos, decided to bring his fictional world to life by transforming Rio de Janeiro 54 into a living museum of Mexico’s aristocratic past.

But here’s the fun part: nobody’s quite sure if Filomeno was real or invented. The cantina displays a striking 1909 portrait of the dashing charro Filomeno, complete with a rather pronounced backside that draws every diner’s eye. Actual person or fictional character? Una nunca sabe, and that’s part of the charm.

150 antiques and one very patient team

Transforming this space into an authentic period cantina meant preserving every possible original detail while both making room for a flourishing restaurant and meeting complex safety codes. The restoration, completed in 2024 after OMR Gallery’s departure in 2015, kept the century-old stained glass windows, hand-painted wooden panels and Austrian crystal chandeliers that had survived over a century of career changes.

The team sourced and installed over 150 authentic pieces from the 1880s to 1915. One centerpiece, a monumental 19th-century Victorian showcase from an old pharmacy, is completely original. The portrait gallery is particularly striking. While each painting evokes period elegance, many are downright entertaining. “Carmencita,” for example, shows a stout child in a blue dress sporting an expression of absolute boredom.

Just like Liebsohn’s novel, the cantina offers a playful, slightly tongue-in-cheek take on Mexican high society during the opulent Porfiriato era.

Dining where poets once worked

An impeccably-dressed waiter gently places a steaming fish fillet in front of me and refills my wine. Before I can take a bite, a mariachi band approaches our table. When my date politely declines a private ballad (grounds for removal!), the singer turns to me. “Would you like to request a song for the gentleman?” I briefly consider it, then decide I’d prefer to eat. “Next time,” we promise, and the band wanders off to another, hopefully more engaging, pair.

The menu was crafted by Chef Alfredo González Rivas, who researched traditional cantina dishes that once brought together Mexico’s working and elite classes. During the Porfiriato era, cantinas served as spaces for debate and networking, making them perfect venues for both business deals and social gatherings. You’ll find options like sopes de tuétano (bone marrow sopes) and chamorro en su jugo alongside classics like mole poblano and Baja fish tacos. Food arrives on glassware, ceramics, and silver-plated serveware reminiscent of the turn of the 20th century.

It’s surreal to think that within this space, Octavio Paz once had an office, Spanish exiles once hid from a dictatorship, and boarding school girls from the countryside studied. And here I am, stuffing my face with guacamole.

A building that refuses to be boring

As our evening wound down and the mariachi band serenaded other tables, I marveled at this building’s refusal to fade into obscurity. While many historic mansions crumble or turn into museums where you can’t touch anything, this one continues to reinvent itself while staying true to its elegant bones.

Before leaving, my date and I take a quick tour and then split momentarily to visit the restroom. While washing my hands, I notice that the walls are adorned with rather risqué posters of handsome Mexican men. I swear I took a photo. Only, I can’t find it in the stacks of visual snapshots that live in my Photos App. Was it real? Or did I imagine it? I guess, in the end, it doesn’t matter.

View this post on Instagram

Whether Filomeno was real or invented hardly matters either. What matters is that this building — with its century of wild career changes — proves that the best way to honor the past might just be to keep living in it, one dinner at a time.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog or follow her on Instagram.