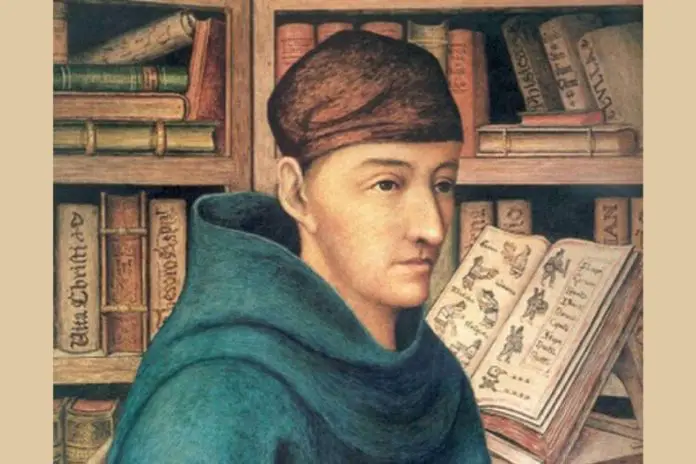

Mexico has several reasons to be grateful to a 16th-century Franciscan missionary named Bernardino de Sahagún. Foremost among them is that his work as a chronicler is invaluable for understanding pre-Columbian Mexican history and culture. Sahagún authored a monumental record of knowledge that might otherwise have been lost forever. Discover the story of a man who set out to change a culture but ended up preserving it forever.

Early life and academic background

Bernardino was born in 1499 in Sahagún, a small town in the León region of Northern Spain. Like many in the country at the time, he was raised in a devoutly Catholic environment. His strong inclination towards religious life from an early age led him to join the Franciscan order and study at the prestigious University of Salamanca, where he was exposed to the humanist ideas of the Renaissance.

In 1521, Spanish conquistadores led by Hernán Cortés conquered the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan. Eight years later, Sahagún was sent as a missionary to New Spain because of his outstanding academic achievements and strong religious devotion.

The Franciscans prioritized evangelizing Indigenous peoples in their native languages. Bernardino de Sahagún quickly learned Nahuatl, the language of the Triple Alliance — better known as the Aztec Empire — to help preachers in New Spain. He translated the Psalms, the Gospels and catechism into Nahuatl.

Deep cultural understanding

In 1536, Bernardino de Sahagún helped establish the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, the first European school of higher education in the Americas. This institution served as headquarters for his extensive research. Sahagún’s curiosity led him to explore the Nahua worldview, and his linguistic skills enabled a deep understanding.

Sahagún used a methodology that could be considered a precursor to modern anthropological field techniques. His motives were primarily religious: he believed that to convert the natives to Christianity and eradicate their devotion to “false” gods, it was necessary to understand those gods. “The doctor cannot correctly apply medicines to the patient [without] first knowing from what mood, or from what cause, the disease proceeds,” he wrote.

Sahagún dedicated himself to the study of Nahua beliefs, culture and history. He constantly questioned elders, wise men and priests about the details that interested him. He asked his disciples to record this information in Nahuatl, which he then translated into Spanish.

Although he was first and foremost a missionary, Sahagún’s approach to gathering information from Indigenous sources and collaborating with local informants laid the groundwork for future ethnographic studies and he has been called the “first anthropologist.”

Knowledge in action

Sahagún applied the Franciscan philosophy of knowledge in action. He didn’t just speculate about Indigenous people; he met with them, conducted interviews and sought to understand their worldview. While others debated whether Indigenous peoples were human and had souls, Sahagún focused on learning about their lives, beliefs and ways of understanding the world. Although he disapproved of practices he interpreted as human sacrifice and idolatry, he dedicated five decades to studying and documenting Nahua culture.

The creation and impact of the Florentine Codex

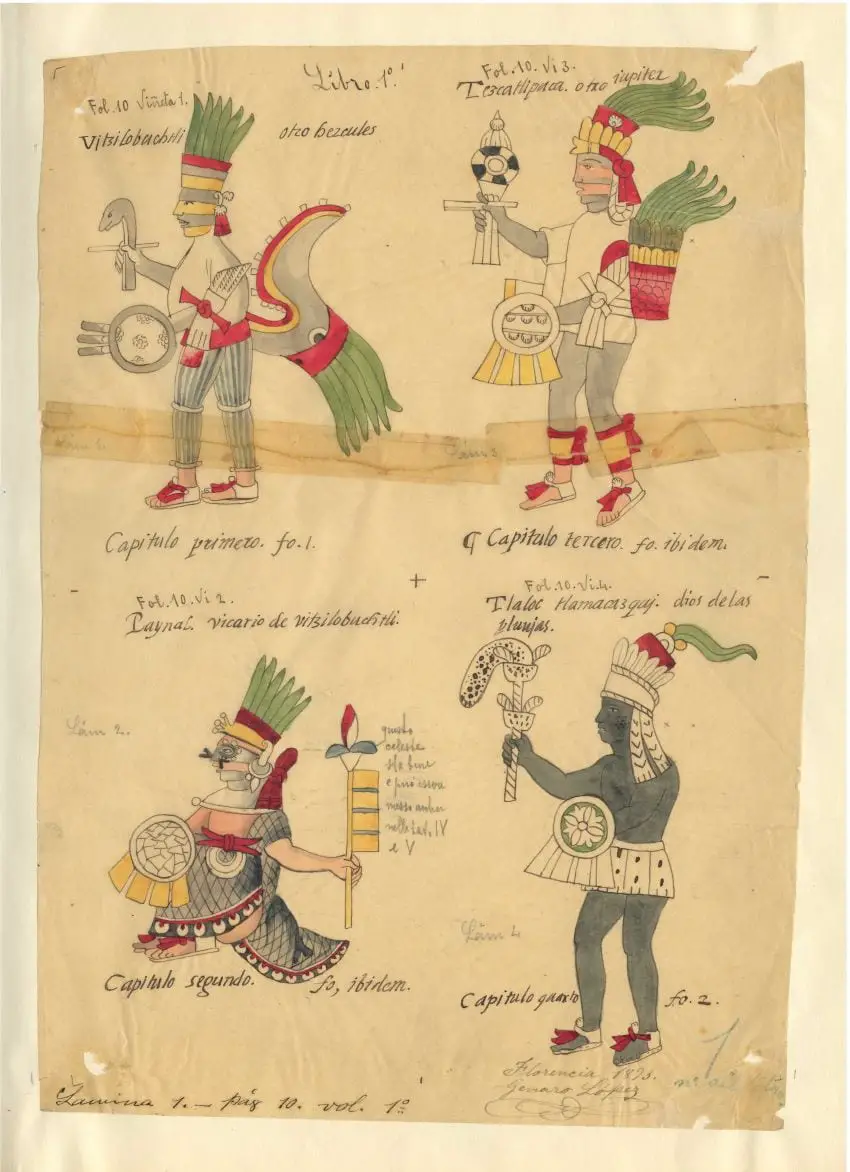

Sahagún’s magnum opus, The Florentine Codex, is widely regarded as one of the most reliable sources of information on Mexican culture and the impact of the Spanish conquest. A treasure trove of ethnographic, archaeological and historical knowledge, it consists of 12 volumes and 2,500 illustrations, documenting the life and beliefs of the Mexicas and other Nahua peoples.

Actually titled The General History of the Things of New Spain, this work was created by Sahagún in collaboration with Nahua elders, scholars and artists over the course of decades. The codex is written in parallel columns of Nahuatl and Spanish, preserving both knowledge and language. Upon its completion in 1577, the manuscript was sent to Europe, where it became part of the Medici family’s library in Florence, hence its name.

Clashes with the Church

Sahagún faced opposition from those who believed that his efforts to document Indigenous cultures were inappropriate, as they could help preserve Indigenous religion. His adversaries tried to stop him in every way possible, resulting in intellectual persecution and frequent transfers from one church to another.

Bernardino de Sahagún’s work often clashed with the Church’s primary goal of eradicating native beliefs. His respectful approach contrasted sharply with the more aggressive methods of conversion favored by missionaries, who sought to quickly replace native beliefs with Christian doctrine.

Some members of the Church believed that Sahagún’s work could inadvertently encourage Indigenous people to cling to their traditional practices. His detailed documentation of Nahua rituals and deities was seen by some as preserving the very idolatry the Church aimed to eradicate.

Rediscovery and modern recognition

The Church’s distrust of Sahagún’s work culminated in the confiscation of his manuscripts. Although he had supportive allies, Sahagún never regained control of his original documents. Fortunately, these manuscripts have since been published and translated, revealing the depth of Sahagún’s contributions.

Views of Sahagún’s work, controversial in its own time, continue to change today. While a previous generation of researchers saw him as a proto-anthropologist driven by the search for knowledge, contemporary academics center on the fact that he was a missionary who saw Indigenous religious practices as something to be eradicated. Modern scholars also emphasize the idea that Sahagún’s sources were native elites with their own agendas, giving him information that was likely colored by the circumstances of the Conquest.

Despite these debates, the work of Sahagún and his collaborators is a crucial resource for studying Mexican history. Their detailed records of Nahua culture have provided invaluable insights into the lives and beliefs of the Indigenous people of Mexico before and during Spanish colonialism. Where many of his contemporaries wanted to erase Indigenous culture entirely, through his dedication, Sahagún ensured their stories would be told.

Sandra Gancz Kahan is a Mexican writer and translator based in San Miguel de Allende who specializes in mental health and humanitarian aid. She believes in the power of language to foster compassion and understanding across cultures. She can be reached at: sandragancz@gmail.com