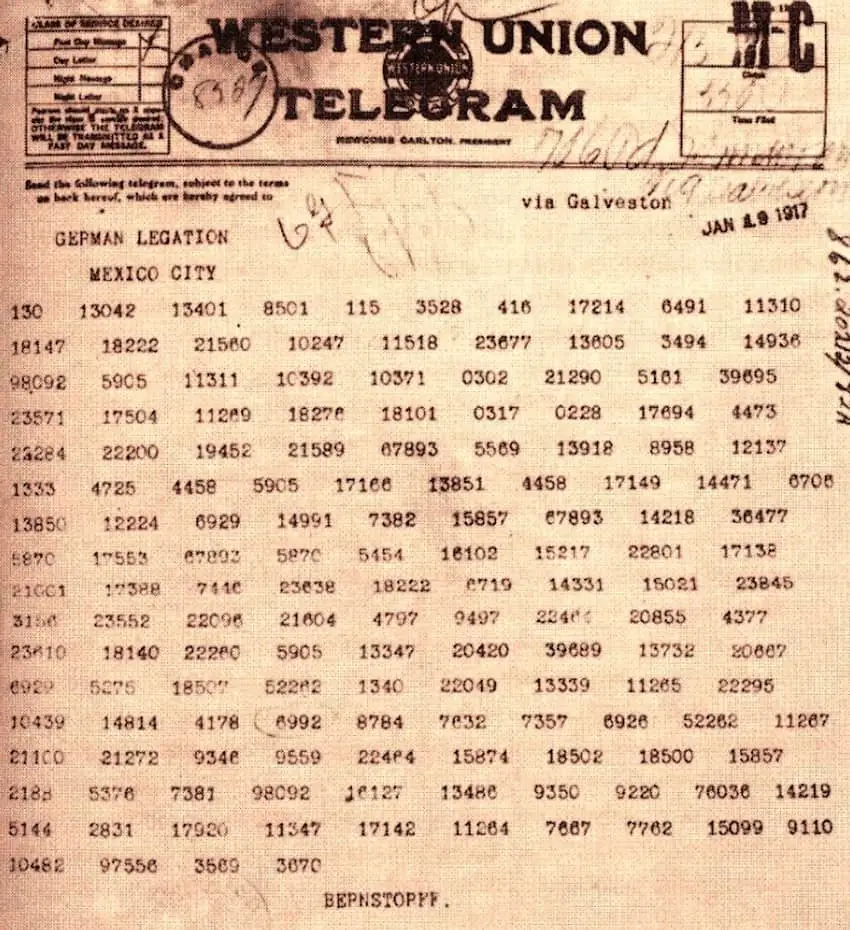

In January of 1917, Nigel de Grey, a member of the cryptanalysis section of the British Admiralty — also known as Room 40, for the room in the Admiralty building which housed the team of top cryptanalysts – finished deciphering a coded communiqué from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmerman to Heinrich von Eckhardt, Germany’s ambassador to Mexico. De Grey immediately understood the significance of the secret plans he had just uncovered.

This message, which we now know as the Zimmerman Telegram, was destined for Mexican president Venustiano Carranza and contained two critical pieces of information. First, the Germans planned on resuming unrestricted submarine warfare, which had been curtailed through the 1916 Sussex pledge. Second, Germany was proposing that Mexico join the war as its ally. In return for this alliance, Germany would provide financial support and join Mexico in a military engagement with the U.S. to recover some of the territory lost in the Mexican-American War – namely Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.

Up to this point, the United States had remained neutral in what was being called the Great War. The British were desperate to bring the U.S. into the war and de Grey felt this telegram could accomplish that. For its part, Germany was desperate to keep the U.S. out of the conflict and hoped that with Mexico’s help they could keep U.S. troops busy protecting their southern border and at the same time deplete American resources. Mexico had also remained neutral. The country was still embroiled in civil war, and Carranza wanted to avoid agitating either their neighbor to the north or their European friends.

Germany had shown an interest in Mexico for years. During the Mexican Revolution, the German spy Felix Sommerfeld was sent to Mexico to ingratiate himself with revolutionary leaders. He succeeded in becoming a confidante to former president Francisco I. Madero (1911- 1913), Pancho Villa and Carranza himself.

Sommerfeld and Madero were so close that when Madero became president, he put the German in charge of creating and running Mexico’s secret service – the perfect position for intelligence-gathering. Madero and Sommerfeld were rarely seen apart. At the same time, Sommerfeld was sending regular intelligence dispatches to Germany.

By 1914, Mexico was a hotbed of political intrigue and German espionage. By 1917, Germany had reason to believe Mexico might be ready for an alliance.

Meanwhile, in March 1917, the British passed the Zimmerman Telegram along to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, who had just been re-elected to a second term, largely thanks to the slogan “He kept us out of war.” Wilson was stunned by the audacity of the Germans, reportedly muttering “Good Lord!” repeatedly as he read the message. For Wilson, the telegram changed the calculus on entering the war, and he decided to release the contents to the press.

The telegram’s release was met with public outrage and galvanized support for going to war.

According to the author of “Codebreakers,” David Kahn: “No other single cryptanalysis has had such enormous consequences.”

Some government officials suspected that the telegram was a British ruse to draw the United States into the war. Those suspicions were soon dispelled, however, when Zimmerman himself confirmed the message’s authenticity in a public speech only a few days later.

On April 2, Wilson convened a joint session of Congress and called for a declaration of war.

In Mexico, Carranza had received the telegram. It is unknown whether he seriously considered the proposal. His relationship with the U.S. was a little shaky: Carranza’s rival Pancho Villa had attempted to provoke a crisis between the two countries by raiding Columbus, New Mexico in March 1916. In response, Wilson sent General John J. Pershing on a punitive expedition into Mexico to capture Villa; and though war between Mexico and the U.S. was narrowly avoided, anti-U.S. sentiment was inflamed across Mexico. .

Carranza turned the German proposal over to a military commission for an assessment. The proposal was officially rejected once the commission decided there was no benefit to accepting it. The commission noted that the German government’s promises of “generous financial support” were unreliable, as it had refused financial help to Mexico in 1916. Moreover, still embroiled in civil war and militarily weak, there was no reason to believe that Mexico could actually beat the United States. War would also jeopardize Mexico’s international relations. Even if it did win, the lost territory of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona would be difficult to govern, as it was now populated by an armed, English-speaking population.

Ironically, the mysterious German spy Felix Sommerfeld – who was secretly in charge of the Mexican portion of Germany’s war strategy – became Carranza’s liaison with President Wilson, as he also had well-placed contacts in the United States. There is no indication that Carranza knew Sommerfeld was a German spy.

In the end, Mexico did not enter World War I or start a conflict with the United States, whose entry into the war on the side of the Allies was instrumental in ending the conflict.

Mexico benefited in another way by refusing Germany’s proposal.

The United States had not, up to this point, recognized the political leadership in Mexico. To ensure Mexico’s neutrality in World War I, the United States officially recognized the Carranza government on August 3, 1917, leading to a better relationship between the two countries.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.