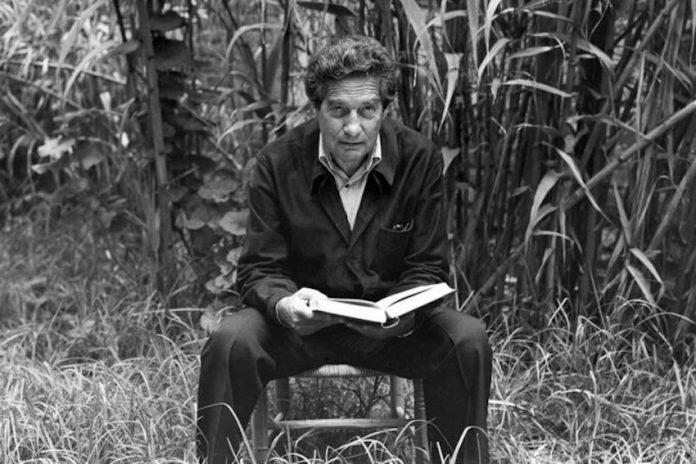

Writer and poet Octavio Paz once wrote “Solitude is the profoundest fact of the human condition. Man is the only being who knows he is alone.” Today, the author continues to exert an enormous social legacy on Mexico — but what makes Octavio Paz so important, some 26 years after his death?

During his 84 years of life, he positioned himself at the center of political, cultural and intellectual discourse during different historical events of social change for the world. Paz sought to pinpoint and describe the essential values of modern society, like democracy and peace. Most of all, his legacy leaves us a profound reflection of what it means to be an intellectual and an activist, and the importance that lies in combining them both.

Early life and education

Octavio was born amid the Mexican Revolution, a war that took his father away from home. Octavio and his mother moved into his grandparents’ house in Mixcoac, then one of the municipalities that made up Mexico City. The area left a profound effect on him, and Paz is memorialized in the neighborhood’s metro station.

The young Octavio was raised mostly by his mother and grandfather. His grandfather Irineo had been a writer and had spent much of his life writing political manifestos against Santa Ana and Benito Juárez’s government.

Political and intellectual discussions were common in Octavio’s house while growing up. As a result, he became involved in them from a very young age, inspired by his father and grandfather’s aspirations to make Mexico a better country and a better place to live. However, he also fell in love with his grandfather’s personal library and realized early on that his “destiny was not an active life, but one of words,” he told Canal Once in 1993.

In 1930, he started high school at the prestigious San Ildefonso school, where he was introduced to an intellectual world that immediately resonated with him. Many celebrated poets and writers had studied there as well, some of whom became his teachers. There, Paz began to get involved in different publications and started writing poetry.

In an interview with Canal Once in 1993, he said that a lot of his friends believed in fascism, and the majority in communism. “Although I was never part of the communist party, I was violently inclined towards the left,” he said. During those years, he became very involved in social and political activism, which landed him in jail multiple times.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Octavio Paz started studying law after graduating from high school. There, he met his future wife Elena Garro. Garro, who later became a renowned writer and one of the voices of Mexican classical literature in her own right, was a dancer and choreographer at the time. They married when Paz was just 23 years old. In 1939, Elena gave birth to their only daughter, Elena Paz Garro. It is said Paz never had a good relationship with his daughter, possibly due to the nature of his own relationship with his father — quiet, absent, and cold. The couple split in 1959.

He abandoned his studies at law school just one class shy of graduating.

Octavio Paz as a diplomat

Because his literary legacy was so impactful, many people forget that Paz was a diplomat for twenty-five years of his life. In 1943, when he received a Guggenheim scholarship and moved to the United States, he began working at the Mexican consulate in San Francisco. He lived there for two years, where he discovered some of the poets that most inspired his work, such as Robert Frost and E.E. Cummings.

After San Francisco, he was relocated to Paris to serve as third Secretary of the Embassy in France. In Paris, he became part of a network of world-renowned philosophers that included the likes of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus.

Paz also served as the Mexican Ambassador to both India and Japan, as well as consul for two countries that had no diplomatic relationship with Mexico before his arrival: Sri Lanka and Afghanistan.

After the tragedy of the Tlatelolco Massacre in 1968, Paz’s disappointment in the government led him to resign as an Ambassador, an act which turned him into a political enemy and forced him to move to England.

The Labyrinth of Solitude and what it means to be Mexican

Diplomats in Paz’s time were poorly paid, and so he lacked the financial freedom to visit Mexico. This, he told Canal Once, forced him to think about Mexico differently. “There were many perspectives to be had: Mexico was not only an everchanging and complex country, but there were also different ways to look at it. One of those was to look at it from afar.”

This reflection led to the coming together of his most important work. For many years, Paz had published essays on the nature of Mexican culture and “Mexicanism” in different literary magazines, which were the seed of what ultimately became the acclaimed Labyrinth of Solitude in 1950.

In that same interview, he mentioned that maybe one of the reasons why he became obsessed with Mexican identity was his time at school. He went to primary school partly in the United States — where they made fun of him for not speaking good English and being a foreigner — and partly in Mexico, where they teased him for being a “gringo.”

After the political chaos caused by the Tlatelolco massacre, President Echeverria wished to normalize relations between the government and prominent Mexican intellectuals, who had largely dissented (although notably, these did not include ex-wife Elena Garro). He welcomed Paz back to the country, and made the Labyrinth of Solitude mandatory reading in public high schools, some twenty years after its publication.

Octavio Paz’s Legacy

Apart from the Labyrinth of Solitude, Paz had an enormous body of work. Mostly poetry and essays, these paint a vivid picture of not only his personal life, but also the historical and cultural context that changed and affected the world while he was alive. Aside from an immense gift to Mexican literature, they provide us with insight on how to make sense of social and political change at the crossroads of revolution, intellect, and art.

Finally, Paz attempted to describe the nature, culture, and characteristics of what it means to be Mexican in a tangible way. How effectively the resulting literature did that is subjective, but he gifted us with something priceless: the certainty that ours is an identity so special and complex that it deserves its own dictionary.

Montserrat Castro Gómez is a freelance writer and translator from Querétaro, México.