La Catrina is perhaps the most recognizable symbol of Day of the Dead. In the week leading up to the Day of the Dead, Catrinas and skeletal images stare back at you from shop windows, T-shirts, vendors’ stands, and festivalgoers.

Typically the Catrina is depicted in an elegant dress sporting a bonnet adorned with flowers, feathers and even miniature skulls. Her attire proclaims that this is a festive occasion, a day for celebration.

But the presence of La Catrina in Mesoamerican mythology makes a much deeper statement regarding the way indigenous peoples view death. Colorado State University assistant professor Dr. María Ines Canto says that La Catrina was born from several elements, including “the relationship that indigenous cultures had with death.”

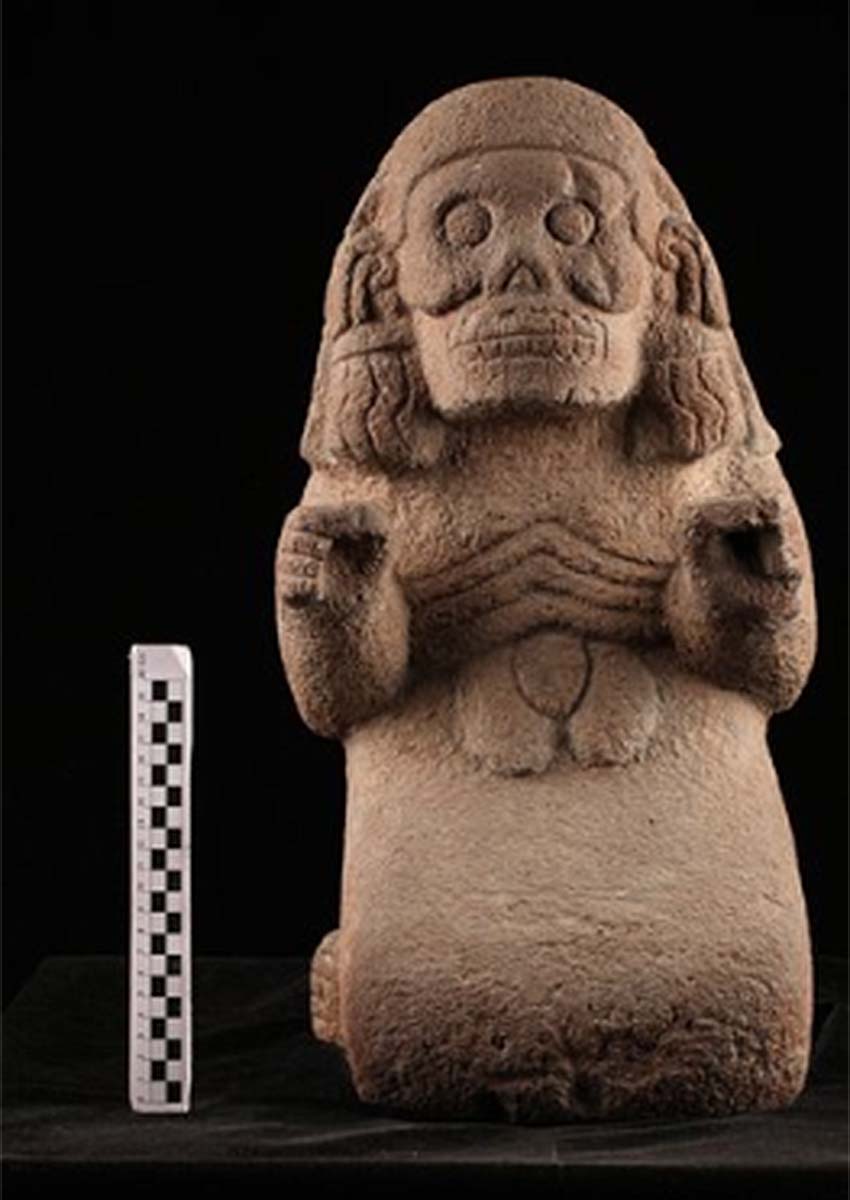

The first “guardian of the afterlife” was Mictecacíhuatl — the queen of the Mexica underworld, known as Chicunamuctlan. It was her role to look after the bones of the dead.

The Mesoamerican peoples believed that most of the dead take a journey through nine levels of Chicunamuctlan and that Mictecacihuatl was the guardian of the ninth level. These ancient peoples believed that death was a time to celebrate your ancestors and loved ones who had passed on to the next leg of their journey.

The myth and her name vary regionally, but she is always present. For example, in Oaxaca, legends refer to her as Matlacihua in Nahuatl— “the woman who entangles” or “the huntress.” She punishes womanizers and drunken men who mislead and bring harm to unsuspecting women.

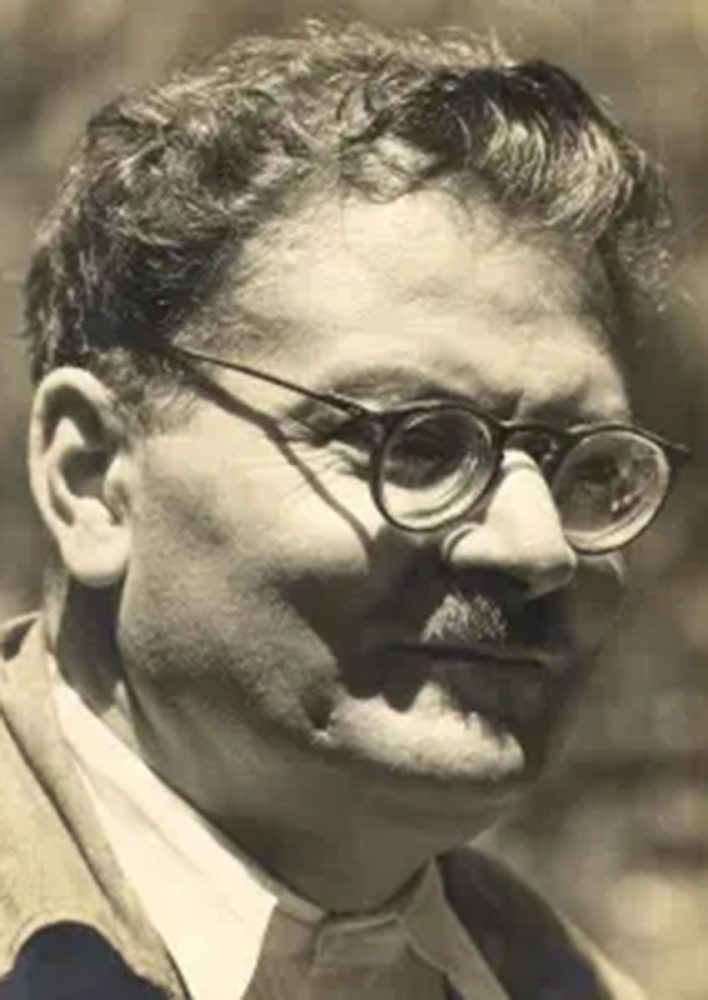

The modern image of La Catrina first made an appearance in 1910 in an etching called “Calavera Catrina” by José Guadalupe Posada — the father of Mexican printmaking. Posada was known for his societal and political satire, which often appeared in the Mexican press.

Bertha Rodríguez, chief operating officer at San Francisco’s Mexican Museum, believes that the image poked fun at Mexico’s street market vendors who stopped selling corn, a traditional Mexican staple, and began selling garbanzo beans instead.

“They were women who were poor but [who] would wear European clothes and try to look European, and they would deny their indigenous roots. It was a critique of the masses, not of poverty.”

The original print by Posada shows a female skeletal figure wearing a French hat decorated with ostrich feathers but not wearing any clothing. Rodríguez explains that “Posada was saying to these women, ‘You don’t have anything, but you are still wearing a French hat.’”

University of San Diego associate professor Dr. Antonieta Mercado explains that “Posada painted many other skulls and skeletons and used the trope of skeletons to satirize and criticize politicians and public figures of the time.”

“La Calavera Catrina” was not only a statement on Mexican women who tried to emulate Europeans but also a satire about the European obsessions of President Porfirio Díaz, who was known for donning layers of makeup to make his skin look white and wearing the European fashions of the time.

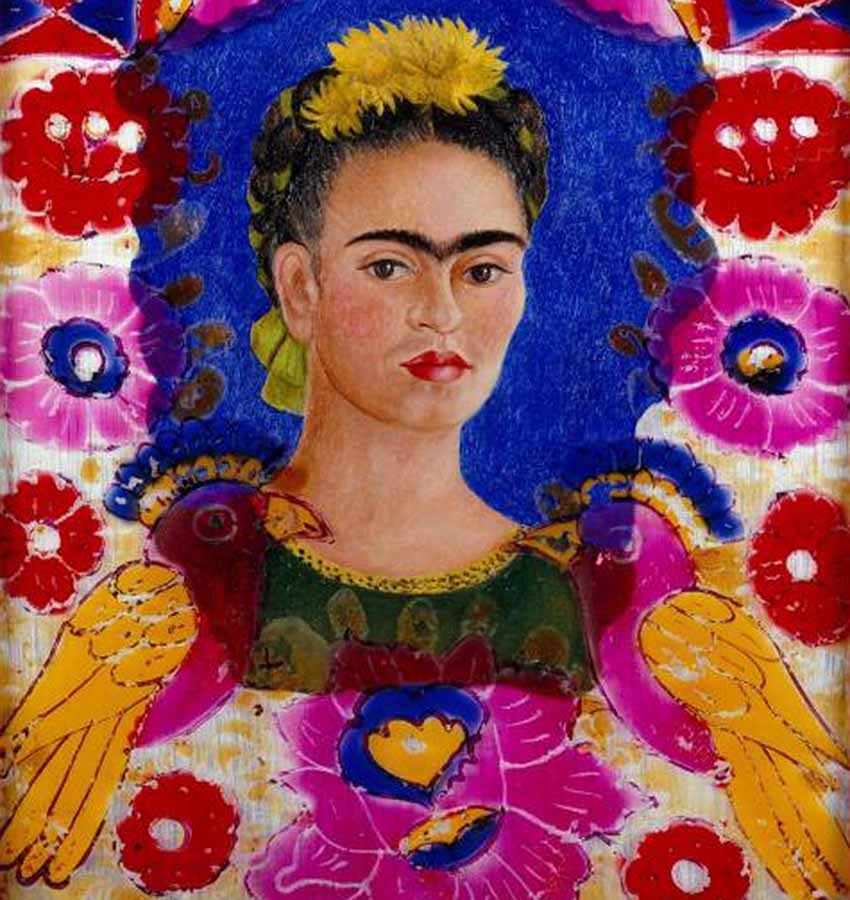

La Catrina was further popularized later by Diego Rivera in his mural “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central,” (1947–1948). This cultural treasure — located at the Diego Rivera Mural Museum in Mexico City — covers 400 years of Mexican history and La Catrina.

In Rivera’s mural, La Catrina is front and center, wearing an elegant full-length gown. On one side, Diego has positioned Posada, the creator of the original La Catrina. On her other side are Frida Kahlo and the artist himself, represented as a boy.

According to Dr. Mercado, artists like Rivera “started a tradition of vindicating indigenous iconography in the 1930s” because they considered the Mexican Revolution a war that vindicated the rights of the common people, not elites.

The image of La Catrina can be seen in many different forms — from sugar skulls being sold by vendors to large papier mache statues in plazas to the elaborate clothing on skeletons at festivals.

She is also big business: her image can be found on T-shirts, handbags, tablecloths, shoes and even children’s school backpacks. It also became popular in Mexico to combine the image of Frida Kahlo with La Catrina to create the Frida Kahlo Catrina, which resembles Frida’s self-portraits.

Although La Catrina’s image has become an emblem of the Day of the Dead, it means so much more than a Halloween costume, and she should not be conflated with iconography from that holiday.

Many Mexican women in Mexico and of Mexican heritage in the United States dress as Catrinas on Day of the Dead to keep their culture alive. Photographer Gustavo Mejía helps keep the Catrina tradition alive from behind the camera.

“The Catrina, to me, it means culture, a festive symbol of the Día de los Muertos,” he said.

La Catrina’s elegant dress suggests celebration, her inescapable, sly smile reminding us that there is comfort in mortality — and a reminder that the dead should be remembered, not feared. As portrayed by both Posada and Rivera, she captures the comfortable and intimate relationship Mexicans have with death.

“La Catrina has come to symbolize not only El Día de los Muertos and the Mexican willingness to laugh at death itself, but originally La Catrina was an elegant or well-dressed woman, so it refers to rich people,” said David J. de la Torre, former executive director of the Mexican Museum in San Francisco and board member of the Art Museum of the Americas.

“Death brings this neutralizing force; everyone is equal in the end,” he said.

Posada’s reduction of every person to bones had an apparent message that ‘underneath, we are all the same’ — with the same destiny. His satirical etchings are a societal leveler — no matter which part of society you occupy, death eventually comes to everyone.

It also draws a direct line back to the earliest Mesoamerican beliefs: whatever comes after life, the guardian of our souls is a female.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán last year and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.