“Los mexicanos nacemos donde nos da la chingada gana.”

You might think our CEO, el jefazo Travis Bembenek, coined that phrase, but its proud author was a woman who embodied Mexico like no one else: Chavela Vargas. Born in Costa Rica, she was – by her own insistence – more Mexican than all the tequila she drank.

Her given name was María Isabel Vargas Lizano. She arrived in Mexico at 17 years of age, determined, in her words, “to sing like Mexicans sing.” Over the next seven decades, she naturalized herself through music, not bureaucracy. Her voice became inseparable from the rancheras, boleros, and corridos of our national repertoire. For Chavela, belonging was never about a birth certificate, but instead passion, devotion and truth.

I still tear up when I hear her. Chavela’s voice plumbs the soul. It summons my own nostalgia for childhood afternoons at my grandparents’ rancho.. I hear the sun setting over the hill, the pomegranate trees and the smell of burning wood. I see the faces of my grandmothers — Chavela’s contemporaries — gazing into the distance as the radio played her voice. And yes, I have once and long ago cried thinking of impossible loves, the kind Chavela turned into anthems. In her raspy yet tender voice, I recognize the intimacy of heartbreak.

Born in pain, reborn in song

Chavela’s early life explains that fire. She grew up in San Joaquín de Flores, Costa Rica, where her parents divorced and often ignored her. Sent to live on her uncle’s coffee farm, she was nicknamed “the girl with the snakes.” She learned to work, to hunt, to endure solitude. Her only dream was to escape. At 17, she boarded an airplane north. She believed her future was in Mexico, where music reigned.

Mexico did not welcome her easily. She scraped by with odd jobs — washing dishes, selling snacks, even running a small “maids’ agency” from a used car. By night, she sang in cantinas, busking along Avenida Insurgentes for a few coins. One composer dismissed her cruelly: “You sing so ugly, you shouldn’t even think of singing.” But Chavela refused to be silenced.

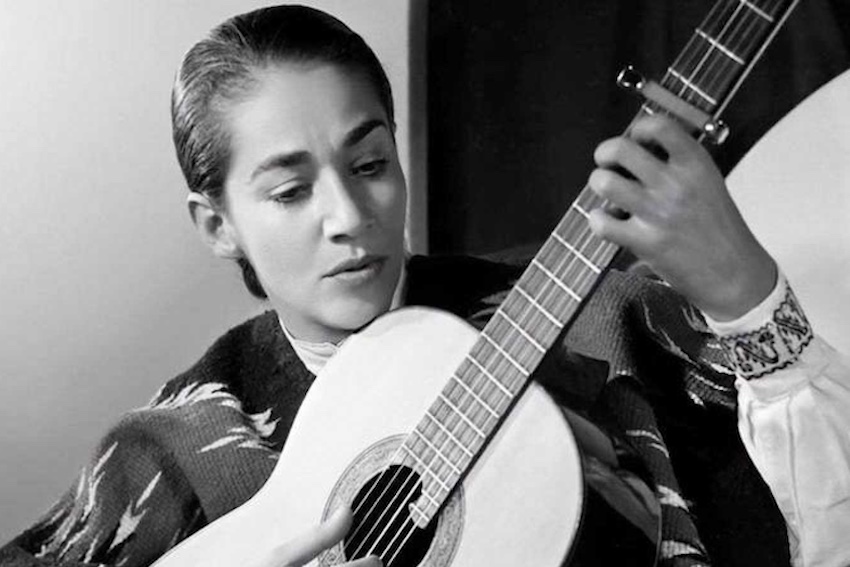

She crafted a persona that was itself a rebellion. She wore men’s pants and charro sombreros, wrapped herself in flamboyant jorongos, smoked cigars and walked unashamed through a conservative, often hostile Mexico. People hurled insults in the street, but she kept singing. She was building not just a career, but character and a myth.

Chavela’s first records

By the late 1950s, artists and poets finally started to take notice. Her first record, ”Noche Bohemia”, appeared in 1961, with encouragement from José Alfredo Jiménez. More albums followed. Her voice — spare, aching, without mariachi adornment – was unlike anything else in Mexican music. Chavela sang love songs exactly as men had written them, without changing the pronouns. Every ranchera she sang was addressed to a woman. She declared her truth without ever announcing it.

Her circle became a who’s who of Mexican art: Diego Rivera, Juan Rulfo, Dolores Olmedo. She and Frida Kahlo shared not only friendship but, according to Chavela herself, desire. “I was dazzled by her face and her eyes,” she confessed. A rumored love affair remains one of Mexican culture’s most tantalizing legends. Frida allegedly confessed in a letter: “Today I met Chavela Vargas. Extraordinary, a lesbian… I wanted her erotically.”

Chavela also delighted in stoking speculation. She once claimed she was hired to sing at Elizabeth Taylor and Mike Todd’s 1957 wedding in Acapulco and spent the night with Ava Gardner. Whether she did or not hardly matters. What mattered was the image. Chavela was a womanizer, a dangerous figure of desire.

And then there was ”Macorina”. Based on a Cuban poem, its chorus — “Ponme la mano aquí, Macorina” — was a whispered provocation. Smithsonian curator Marvette Pérez later called it “the first and most famous erotic lesbian song” of its time. In Chavela’s performance, there was no ambiguity about who she was singing to.

Exile and resurrection

But the price of defiance was steep. By the 1970s, Chavela had been effectively blacklisted from major media. Rumors swirled that her love affairs, particularly with women of influence, had made her a persona non grata. Combined with her heavy drinking, it led to her disappearance from public life. For nearly two decades, she vanished. Many assumed she had died.

Then, in 1991, she reappeared. At 72 years old, Chavela walked into a small Coyoacán nightclub, El Hábito, and sang again. Her voice, aged and cracked, was more powerful than ever. That night, Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodóvar was in the audience. He became her champion, bringing her to Europe, featuring her in films and staging her comeback.

In 1994, she sang at Paris’ Olympia. In 2002, her voice appeared in ”Frida”, thanks to Salma Hayek’s insistence. And on September 15, 2003, on the eve of Mexico’s Independence Day, Chavela Vargas walked onto the stage of Carnegie Hall. At 83, she turned one of the world’s most revered concert halls into a cantina. The audience shouted requests, applauded wildly and cried with her. As biographer Benjamin Moser recalled, “Here was a Mexican grandeur we had not seen in years, and would never see again.” The recording of that night still brings me to tears.

In the last decade of her life, Chavela was showered with honors: a Latin Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, Spain’s Grand Cross of Isabel la Católica, and, in 2012, a triumphant concert at the Palacio de Bellas Artes — the home she had long been denied. A few months later, she died at 93 in Cuernavaca. Her final words, as reported on her official website, were: “Me voy con México en el corazón.” I leave with Mexico in my heart.

Essential Chavela

For anyone discovering her today, here is where to begin. These songs are my own entry points, pieces I believe are essential to understanding this singular voice of Mexico:

- “Macorina” – Forget the speculation. Listen instead to the sensuality with which she delivers this song. It is pure provocation.

- “Rayando el Sol” – A Manuel M. Ponce classic, a farewell bathed in the colors of a Mexican sunset. My personal favorite: painful in a low, quiet register.

- “Volver, Volver” – How many times were you told to forget someone, to end it once and for all—only to return? This is love’s stubborn refrain.

- “Toda una vida” – A bolero’s eternal vow, fragile and sensual in Chavela’s voice. “Toda una vida te estaría mimando…” She makes it sound like both a promise and a wound.

- “Las Ciudades” – Written by José Alfredo Jiménez, Chavela called it a prayer, and she sang it with reverence. Every city becomes a lament for an impossible love.

- “El último trago” – Tequila, nostalgia, camaraderie, pain, resignation – this song distills her essence.

- “Desdeñosa” – A Yucatecan tune from the 1940s, a tropical way of saying “you’re so vain.” Listening, I picture myself in a hacienda hammock in Mérida.

Each track is simple – just a guitar or two and her voice – but in the silences between her words, you hear entire lifetimes.

Inheritance of Freedom

At one legendary concert in el Zocalo, Chavela told her audience: “Les dejo mi libertad como herencia, que es lo más precioso que tiene un ser humano.” I leave you my freedom as an inheritance, which is the most precious thing a human being has.

That is what she left us: the freedom to belong wherever our hearts demand, the freedom to be ourselves without apology. Chavela Vargas was Costa Rican by birth, Mexican by choice and universal by truth.

She proved that we Mexicans are born where we decide to belong. And she left us her freedom, which is now ours.

María Meléndez is a Mexico City food blogger and influencer.