Almost everyone has a memory of film, a particular image or moment that, without

realizing it, becomes a part of who they are. Mine dates back to a time when television

had overshadowed the cinema, but weekend programming was a ritual of discovery:

American films, European art pictures at night, and on channels 2 and 9, Mexico’s

golden age classics. Sometimes, there would be advertisements for special screenings

of Emilio Fernández’s films — stories that would come to define Mexican cinema and its

soul.

The cultural power of film is unmatched. Across disciplines — psychology, art,

philosophy — scholars have delved into its influence, seeking to understand how cinema

shapes our collective identity. Why does this art form, born in darkness, become so

deeply embedded in the fabric of a nation? Film’s narratives, its framing, its

pacing … these are mirrors of our spirit, our history and our dreams.

The power of film

In Mexico, during the early 1930s, as the nation was forging its modern identity, the

government saw cinema as a vital tool. It was more than entertainment; it was a means

to craft a narrative, to build symbols that could unify a diverse society. State funding

flowed into the industry, transforming film into cultural diplomacy, a way to project

Mexico’s image beyond its borders.

Meanwhile, the upheavals of World Wars I and II caused a halt in European and

American film production. This created space, a vacuum that Mexico eagerly filled.

Talent, ideas and support began to flow into the country, making it a fertile ground for

cinematic innovation.

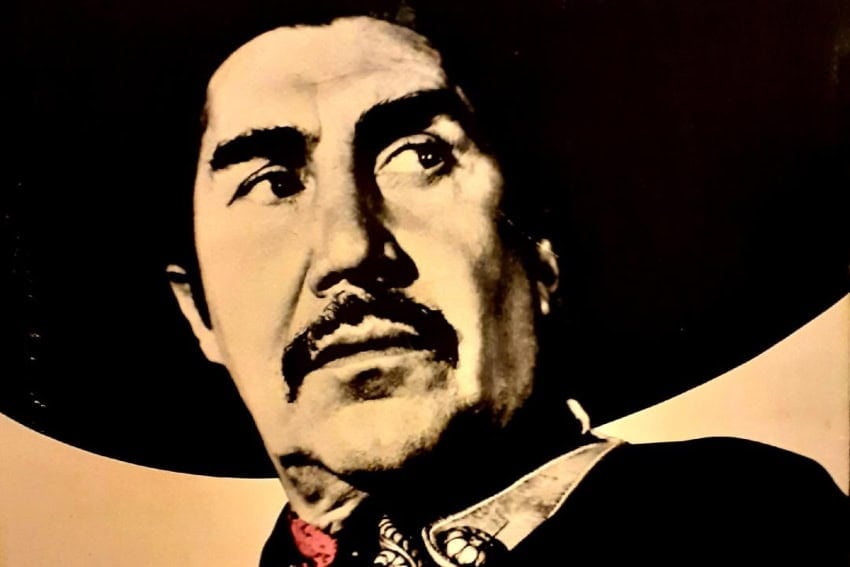

Among the giants of that era, Emilio “El Indio” Fernández looms larger than most. His impact on Mexican culture is profound, shaping not only our cinema but our

understanding of ourselves: our stories, our struggles, our pride.

The architect of Mexican identity

Fernández’s life reads like a myth. Born on March 26, 1904, in Coahuila, he was the son

of a revolutionary general in Pancho Villa’s army and a Kikapú woman. His nickname,

“El Indio” was a badge of identity he wore proudly, embodying his roots.

In several interviews, he told the story of his life as if it were out of his movies. He

recalled as a child riding horses, carrying guns, and living on the fringes of the

revolution, an upbringing that would come to define his screen persona: a rugged,

resilient archetype of Mexico’s essence. His leadership talent was apparent

early, so much so that Felipe Ángeles, a renowned revolutionary figure, recommended

him for military training. He confessed he didn’t want to compete with his father, and he

chose a different battlefield: cinema.

After a stint in prison at nineteen, Fernández escaped, and in 1928, he arrived in

Chicago. There, he was rumored to have met Rudolph Valentino, though the dates tell a different story. Valentino, dying in New York, supposedly left instructions for Fernández to carry Mexico’s image beyond borders. His wanderings took him to California, where he

stayed for nine years. He connected with other Mexicans, including a former

presidential candidate who convinced Fernández that cinema’s cultural reach was more

potent than any weapon or war.

His moment came when he watched Sergei Eisenstein’s unfinished masterpiece, “¡Qué Viva México!” The images — raw, revolutionary, poetic — set him on a new path. He

decided then to learn the craft of filmmaking, to return home and tell Mexico’s story

through film. During those years, he performed at dance clubs where Xavier Cugat

played, worked as an extra. He learned by watching. With a borrowed camera, he

experimented, practiced and dared.

The Golden Age of Mexican Cinema

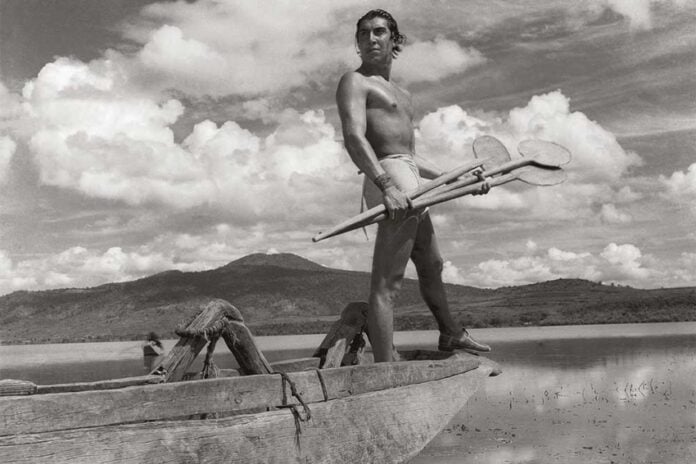

In 1933, Fernández returned to Mexico and directed his debut, “La Isla de la Pasión.” His

breakthrough came with “Janitzio” (1934), where he starred, danced and wrote. But it

was “María Candelaria” (1943), which would forever be etched into the cultural fabric of

Mexico. That cemented his legacy. Working alongside legendary talents — cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa, screenwriter Mauricio Magdaleno and actors like Pedro Armendáriz, Dolores del Río and María Félix — Fernández crafted a new cinematic language.

This was the Golden Age of Mexican cinema and between 1936 and 1956, this art

became a mirror for the nation’s soul. World War II’s global upheaval granted Mexico

space to grow its cultural voice. While the world was preoccupied with conflict, Mexico

was rebuilding and modernizing. Hollywood’s resources dried up during wartime, but

Mexican cinema received support both from the government and international

allies, further fueling its rise as a cultural force.

Films from this period reflected the complex realities of Mexican life: its landscapes, its

contradictions, its aspirations. They borrowed Hollywood’s narrative structures but

placed them within our unique contexts — Mexican towns, Indigenous stories,

revolutionary ideals. Artistic influences from José Guadalupe Posada, Dr. Atl and the

muralists fused to create an unmistakable visual style, epitomized by Gabriel Figueroa’s

masterful use of chiaroscuro. His contrast of shadow and light shaped not only Mexican

cinema but also a visual language that remains iconic today. These images of agave fields,

cloud-laden skies and the archetypal Mexican figure are etched into the collective

consciousness. They define the aesthetic of an era and continue to inspire.

Notable films

Among Fernández’s most influential works, “Flor Silvestre” (1943) stands out as a lyrical reflection of Mexican life and song. The film, which he directed, tells the love story of José Luis, the son of a hacendado, and Esperanza, a humble campesina. It blends the nostalgic clichés of the Porfiriato with the stark realities of the post-revolution period, and exposes injustices masked as national progress.

“María Candelaria” (1943), awarded at Cannes in 1946, is a masterpiece that explores

themes of discrimination and cultural marginalization. Set in Xochimilco in 1909, it

follows a couple caught in the troubling gap between revolutionary ideals and the

persistent erasure of indigenous identity, and is a poignant reminder of Mexico’s ongoing

struggle to reconcile its past and future.

“Enamorada” (1946), perhaps María Félix’s most iconic film with Pedro Armendáriz, is a

romantic drama set amidst the upheaval of war and revolution. Félix’s character, the

daughter of a hacendado, falls in love with a Zapatista general, challenging traditional

notions of masculinity and class. The film, rich in humor and layered with political

commentary, questions the very fabric of Mexican identity.

“La Perla” (1947), adapted from Steinbeck’s novel, narrates a tragic story of hope and

despair in La Paz. It became the first Spanish-language film to win a Golden Globe,

signifying Mexico’s expanding cultural reach.

“Río Escondido” (1947) tells of a rural teacher dispatched by the president to a small

town. When she discovers that the local community is controlled by a tyrannical

cacique, she confronts him, symbolizing resistance against oppression. The film

critically examines abuses against the vulnerable.

Impact on Mexican culture

As the novelist Carlos Fuentes observed, the revolutionary upheaval that defined early

20th-century Mexico transcended political and social boundaries — it sparked a profound

cultural renaissance. The revolution not only unified a nation fractured by regionalism

but also forged a shared idea of what it meant to be Mexican. Emilio “El Indio”

Fernández portrayed on screen ideas of pride, courage, resilience and an unwavering

pursuit of progress.

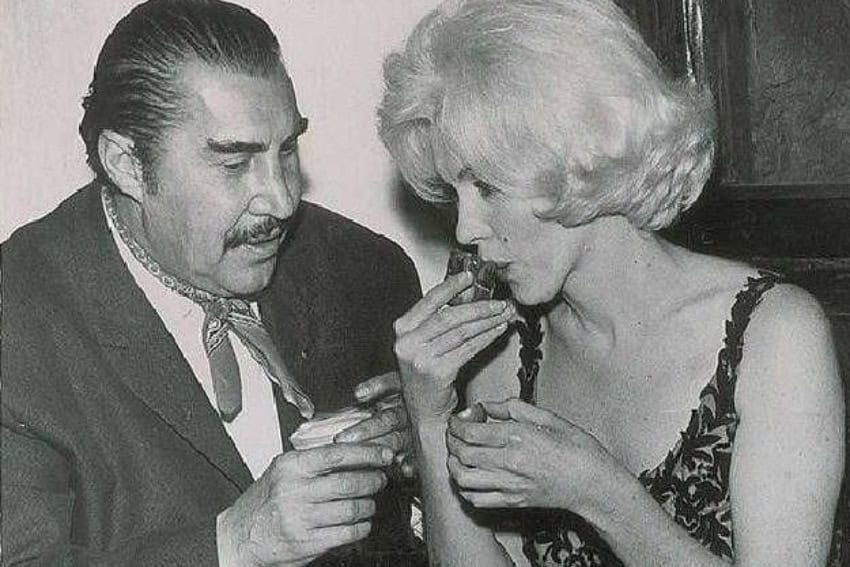

Actors like Pedro Armendáriz, María Félix and Dolores del Río became more than

stars. They became symbols of a modern Mexico — embodying strength, independence

and a fierce sense of identity. Their characters often rode across vast landscapes on

horseback. Women were fierce and determined, yet still bound by traditional structures.

“El Indio” Fernández created a unique cinematic language that resonated deeply with

Mexican audiences. This was art born of a nation seeking to define itself anew.

However, it was not without contradictions. The films often romanticized Indigenous culture — sometimes reinforcing stereotypes, sometimes attempting to elevate

them — thus revealing the complex, sometimes problematic, relationship Mexico has

with its Indigenous heritage.

Legacy

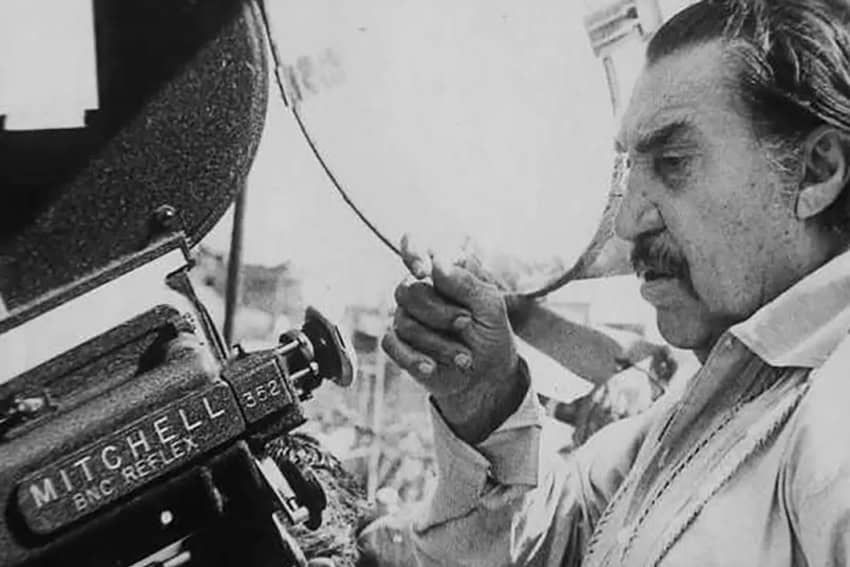

Emilio “El Indio” Fernández Fernández understood the profound role of cinema as a

vessel of identity. His films are more than stories — they are reflections of Mexico’s

history, its hopes, its wounds. By watching his films, you will have a glimpse to the

deeper truths of a nation that was in transformation.

He, alongside Gabriel Figueroa, created the visual landscape and the narrative of

what they perceived as the “real” Mexico. A vision that continues to inspire

photographers, filmmakers and artists; one that showcases Mexico as the land of the

brave, proud and courageous people.

Maria Meléndez is an influencer with half a degree in journalism