Anytime I research and write about a historical figure, I dive in immediately for the chisme. I want to know who they are as people. Married? Divorced? Kids? Pet rabbits? Arrest record? Affair record? Alcoholic? Once I get the dirt, I can start to make sense of their accomplishments. Architect Mario Pani gave me none of that.

So who was this mystical maestro of Mexican modernism?

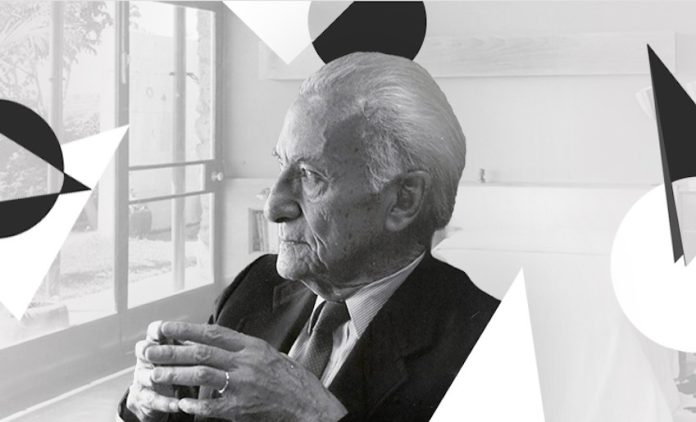

I’ve only determined his marital status thanks to a 1986 photo in which a thin wedding band shines brilliantly on his left ring finger. As to who she was, it’s a mystery. Searches in English, Spanish, and with the assistance of (what I thought was) an all-knowing Artificial Intelligence have turned up absolutely nothing about his nuclear family.

Fortunately, I was lent a book from UNAM’s Architecture Faculty written by Graciela de Garay, which says that Pani married French-Norwegian Margarita Linaae in 1933, who he seems to have met while studying at L’ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. A year later, they moved to Colonia Juarez in Mexico City. Together, they had 7 children.

About his vocation, there is plenty. Pani was born into a life of urban design at the start of the Mexican Revolution. His maternal grandfather worked in the mining industry, his father was an engineer and politician, and his uncle was a well-known engineer who contributed greatly to Mexico City’s hydraulic infrastructure.

In some ways, Pani had his work laid out for him. It seems only natural that he would go on to become one of the city’s, excuse me, the world’s most forward-thinking architects. Notable works include the National Conservatory of Music of Mexico (1946), the Torre Insignia (1962), and UNAM’s Torre de Rectoría (1952).

But the pioneer of modern architecture’s biggest contributions were undoubtedly his housing projects. He believed that everyone deserved a dignified home, and reinvented Mexico City’s landscape by introducing the concept of multifamily housing projects. Pani planned vertical living clusters in a city expanding ever-outward to send skyward the constant influx of new inhabitants.

With a generous government commission, Pani completed the capital’s first high-rise housing block in 1950. Multi-familial Miguel Alemán was modeled on Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation, whose works had a profound influence on Pani. The 12-building complex covered nearly 40,000 square meters and housed over 1,000 apartments. The success of this project led to a second and even more substantial commissioned complex, Multi-familial Presidente Juárez, finished just two years later.

In 1954, Pani started on his master plan for Ciudad Satélite, a residential suburb in Naucalpan de Juárez, Mexico State. He invited Luis Barragán, who then incorporated Mathias Goeritz, to help design a powerful visual that would not only serve as a visible marker from the highway but also as part of a promotional campaign for the project. The resulting towers were inspired by two bold skylines: San Gimignano’s medieval tower houses in Tuscany and the modern skyscrapers of Manhattan. These massive structures can be seen today when driving on Highway Periferico.

The fruitful result of these projects gave way to Pani’s most ambitious design – the Tlatelolco Housing Project. Within the development were 102 apartment buildings, schools, hospitals, and stores, essentially a small urban hub inside a sprawling one. To improve residents’ quality of life, he incorporated light, air, and extensive public spaces for socializing. It ran adjacent to Plaza de las Tres Culturas, a historical representation of Mexico’s Mestizo culture, which would soon be the site of his masterpiece’s first punch in the gut.

In 1968, just two years after the project’s completion, hundreds of students gathered in the square to protest police violence. To this day the details are murky. Who shot who first is the subject of fiery debate. What we do know for certain is that the Mexican military and police force fired relentlessly into a crowd of unarmed civilians. The government initially issued a death toll of 4, while eyewitnesses claimed hundreds. The Tlatelolco Massacre would taint Pani’s architectural vision for years until that vision was all but destroyed in 1985.

When an 8.1 magnitude earthquake rocked the Mexican capital on the morning of September 19, over 400 buildings collapsed, and another 3,000+ suffered serious damage. 12 belonged to Pani’s complex and were fully demolished within 6 months of the disaster. The Nuevo Leon tower fell completely during the 4 horrific minutes that the earthquake lasted, killing around 300 people. Of those inhabitants that survived, thousands fled for fear of the remaining buildings’ instability.

There are reports that Pani faced scrutiny in the aftermath, though few documented responses float around the virtual universe. Nor did it stop him from winning the National Arts Prize in 1986. In 2011, Yoshio Kaneko, a professor at the University of Kyoto, recreated the seismic activity in a lab in an attempt to investigate Nuevo Leon’s collapse (El Financiero). His research brought to light a combination of factors that led to its destruction, including poor design, inadequate conservation conditions, the soil amplification effect, and the earthquake’s intensity and duration. Interestingly, it has proven impossible (until now) to find any official statements regarding the incident — from Pani post-quake, from his critics, or from any critics or supporters of Kaneko’s findings.

But life has both its setbacks and its achievements, and Pani would pass away in 1993 in the same city in which he was born with over 100 of his designs scattered throughout various states in Mexico and Nicaragua. In addition to multiple awards, he would found and edit the highly-successful Arquitectura México magazine which would run for 40 years. While his personal life remains under wraps, his legacy lives on visibly in the urban hodgepodge of Mexico City and beyond.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog, or follow her on Instagram.