Lately, I’ve been hearing more and more Russian spoken on the multicultural streets of Mexico City. As the American-born daughter of Soviet immigrants, my ears are particularly attuned to the cadence of Russian mingling with Spanish. These newcomers are not tourists, and their presence piques my curiosity. What are they doing here? What are they like? And what has their experience in Mexico been?

There’s an unexpected and somewhat humorous connection between Mexican culture and post-Soviet media. During my childhood, I spent a significant amount of time with my Babushka Maya on weekends and after school. Together, we avidly watched “Гваделупе” (Guadalupe), a Mexican telenovela dubbed into Russian and broadcast on Eastern European TV networks.

It turns out that during the early 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, underfunded Russian television studios struggling to meet the public’s rapidly growing demand for entertainment began buying licenses for many Latin American telenovelas and dubbing them into Russian as a quick solution. The Russian-speaking public loved it. The drama of the Mexican telenovela resonated with post-Soviet viewers all too familiar with their own domestic trials and tribulations. Beyond this, there are many other fascinating connections between Eastern European and Mexican history.

No Politics, just pierogies in Mexico’s Russian-speaking circles

Statistics up to 2020 show only a modest number of Russian-speaking immigrants in the area. It was only after the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war in the region that we began to see a greater influx of immigrants from both countries, along with a diverse mix of Eastern Europeans from across the former USSR.

Russians, Ukrainians, Armenians, Uzbekistanis, Georgians, Belarussians and more intermingle, coexisting harmoniously in Mexico despite regional conflicts back at home. Some are economic migrants or entrepreneurs seeking new opportunities abroad, while others are refugees fleeing violence and danger. But whether pushed or pulled, they’ve all converged in this unexpected Latin American enclave, forging new lives interconnected by their shared Eastern European heritage. Supportive WhatsApp and Telegram groups of Russian-speakers in Mexico have amassed thousands of active participants, with one important stipulation pinned in the group rules: no discussion of politics.

A century of asylum in Mexico

Mexico has a history of welcoming Soviet dissidents. When Europe and the United States shut them out, Mexico embraced the socialist “undesirables” who fell afoul of the USSR, from Leon Trotsky and his followers to the later internationalist militants who split from Stalin’s “socialism in one country” policy in the 1930s.

Mexico’s neutral stance — enshrined in foreign policy since 1930 — has made it a haven for those fleeing conflict. This doctrine advocates for non-intervention in external geopolitical issues, allowing Mexico to remain neutral in most international disputes. Mexico’s neutrality helped the country play a crucial role in mediating a solution to the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, the closest the United States and Soviet Union ever came to nuclear war. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, many highly educated Russian immigrants — including scientists, mathematicians, chemists, and physicists — were warmly received in Mexico, taking up positions in various research institutions.

Today, many Russians have come to Mexico to escape mandatory conscription and an authoritarian regime, while Ukrainians are fleeing the direct dangers of war.

Slavs in Mexico: Traditionalists or assimilators?

In conversations with several interviewees and reading through group chat conversations, it became clear that two contrasting mentalities towards life in Mexico have emerged within the Eastern European community: those who cling tightly to their own communities and those who embrace their new surroundings.

Those who remain firmly ensconced in their familiar cultural bubble often perceive Mexico as unsafe. They frequently express nostalgia for their homeland, reminiscing about the life they left behind, complaining about the country’s shortcomings and viewing themselves as separate from the broader Mexican community.

On the other hand, there is an equally prominent set who enthusiastically immerse themselves and celebrate transcultural mingling. This group enjoys embracing Mexican culture and life, quickly picking up the Spanish language. Nastya Krivets, a Ukrainian brand and web designer, embodies this mindset. “My assignment here is to integrate. Not all of the Slavs have that mentality,” she explains. Nastya prefers making international friends through multi-cultural business and networking events rather than seeking out her compatriots.

Despite these differences, Eastern Europeans in Mexico City know how to enjoy life, whether they stick to their own communities or branch out. The community hosts a variety of events, from underground dance clubs to women’s brunch groups and cooking get-togethers. These gatherings often highlight their knack for turning any occasion into a celebration. It’s not uncommon for a dance party to spontaneously erupt, fueled by music from a phone speaker and the enthusiasm of just a few friends in someone’s living room.

Sunshine and smiles

What draws these immigrants to Mexico? Beyond the straightforward immigration process and potential for political asylum, it’s many of the same things that captivate us all: the beautiful weather, the food and the warmth of the Mexican people.

Mexican friendliness contrasts sharply with Eastern Europeans’ often reserved demeanor. Egor Nekrasov, a Russian interviewee, hypothesizes that during the Soviet era, looking too happy could provoke suspicion from authorities. Nastya adds that people of the region are often wary of insincere smiles, making Mexico’s genuine warmth especially appealing.

Then there’s the food. While Russian cuisine has its delights, both Nastya and I agree that it never quite reached the heights of other global cuisines. This stagnation is likely due to the Soviet Union’s restrictive environment and decades of economic hardship, which stifled culinary innovation. In contrast, Mexico offers a vibrant food scene that offers a stark departure from the often simpler, heartier fare of Eastern Europe.

Eastern European ingenuity meets Mexican opportunity

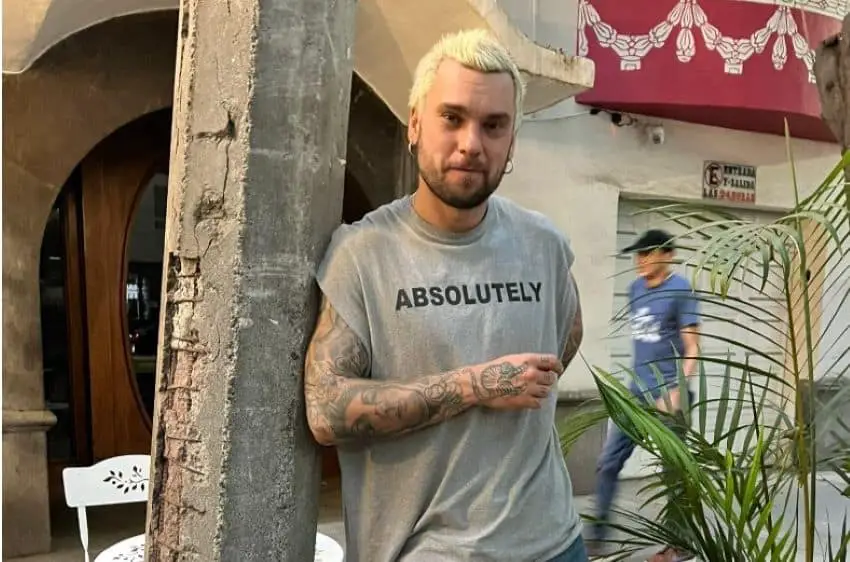

Beyond the cultural draws, Mexico offers fertile ground for business opportunity, which allows the post-Soviet spirit of ingenuity — often born of necessity — to thrive. Egor Nekrasov expresses his admiration for his compatriots: “I see them around the world and I’m impressed.” He says. “They know how to hustle, they know how to make money and survive under the most adverse conditions. They’re like sharks. They try everything.” Egor himself embodies this ethos, juggling an array of hustles from tutoring to bartending to curating vintage pop-up events around the city for his brand Chinaski Vintage.

In Roma Sur, Russian entrepreneurs Igor and Vadim exemplify the scrappy entrepreneurial spirit. A former restaurateur and classical pianist, respectively, Igor and Vadim recently launched Sobaka Pizzeria. After finding a small space and remodeling it themselves, the two bought a portable personal-sized pizza oven and now serve the community with Sobaka’s fresh, simple menu. The pair have found it significantly easier to launch and sustain a small business in Mexico than in Russia.

Entrepreneurial stories like this are plentiful. Egor jokes about a friend who bought an enormous quantity of coffee beans and is now hustling to sell them around town. These stories reflect the dynamic and enterprising nature of the community in Mexico City.

Slavic businesses to check out in Mexico City

Some other Eastern European businesses in the capital include:

- Boris Delicatessen: A hidden gem located next to the Russian Embassy, this store offers a variety of Eastern European goods, from matryoshka dolls to canned and deli specialties, including frozen vareniki.

- Kolobok Restaurant: Established in 2001, this popular spot now boasts multiple locations in Nápoles, Santa María la Ribera, Polanco and Escandón. It offers a wide variety of Slavic and Baltic dishes including borscht, vareniki, shuba and sweet syrniki.

- Escuela de Idioma y Cultura Rusa: This Russian school in Mexico City offers classes, courses and workshops on Russia, its people and its language.

- Le Beauty Studio: Ukrainian-owned, this studio exemplifies Slavic beauty expertise. “Slavic beauty masters are renowned worldwide,” says Nastya Krivets. “The beauty standards are so high that you can always expect exceptional service.”

“Contrary to stereotypes, it takes more than a couple of shots of strong vodka to get Slavs to open up and bond,” says Egor Nekrasov. But once you’re in, you’re in for a fascinating and lively adventure. To be sure, as the Eastern European influence continues to blend in with the warm cultural fabric of Mexico, its contribution promises to be an exceedingly interesting one over time.

Monica Belot is a writer, researcher, strategist and adjunct professor at Parsons School of Design in New York City, where she teaches in the Strategic Design & Management Program. Splitting her time between NYC and Mexico City, where she resides with her naughty silver labrador puppy Atlas, Monica writes about topics spanning everything from the human experience to travel and design research. Follow her varied scribbles on Medium at https://medium.com/@monicabelot.