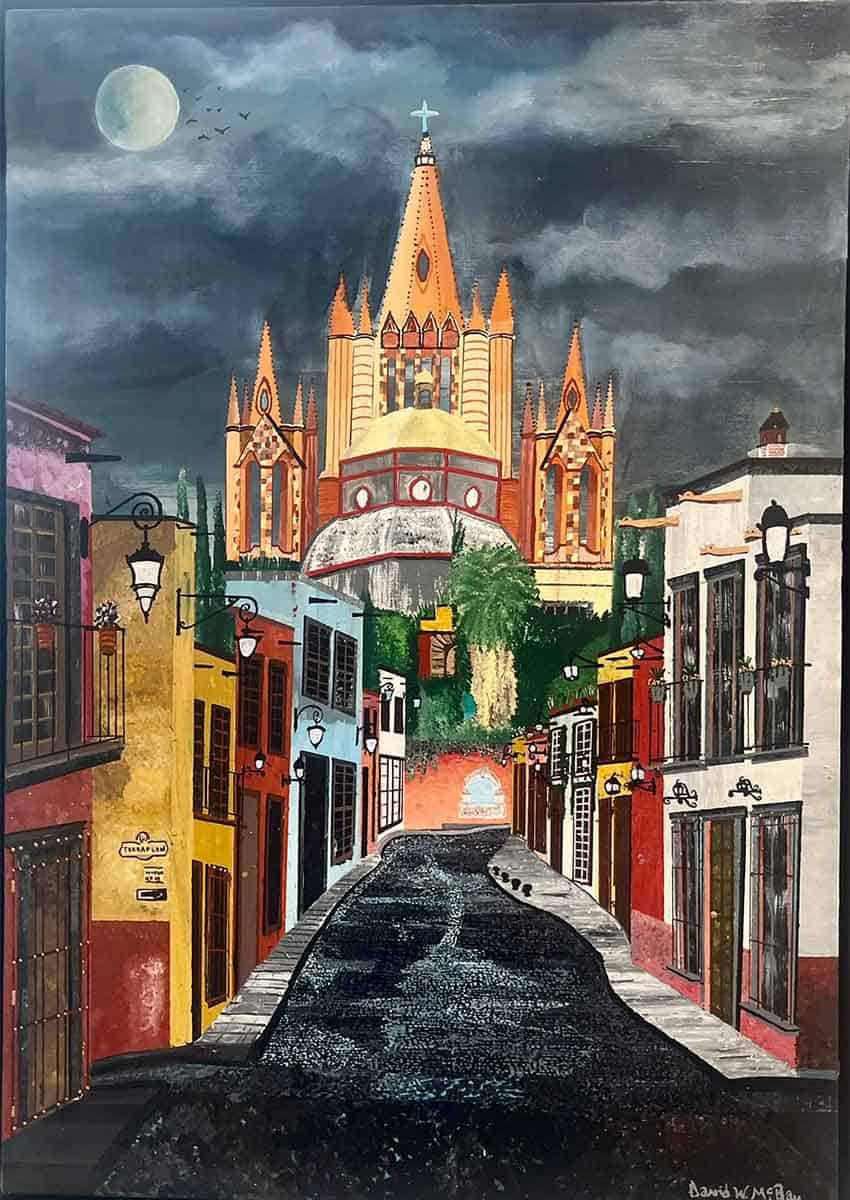

Today, San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato is world-famous for its ambiance. After all, Condé Nast declared it the “world’s best place to live” three times. But one important feature is its artists community, second in Mexico only behind Mexico City despite its small size.

Without a doubt, the establishment of an art school in the once-almost-deserted town not only revived the pueblo’s fortunes but also made it one of the world’s most unique places to live.

That school, the Instituto Allende, still exists today and still offers an art degree (in English!). Although it was certainly the spark that got things started, it is also fair to say that San Miguel’s reputation as an artist colony — as well as its position as the No. 2 art market in Mexico — has come more from the community that the school inspired over the past decades.

After getting off to a promising start, the school’s fortunes began to decline, with student strikes, a failed collaboration with legendary muralist David Siqueiros, problems with locals and the opening of other opportunities for foreign artists in Mexico. The campus moved to the edge of the town.

Today, there are art classes still to be had at the old monastery it originally occupied, but that is now the Centro Cultural Ignacio Ramírez “El Nigromante,” and not the Instituto.

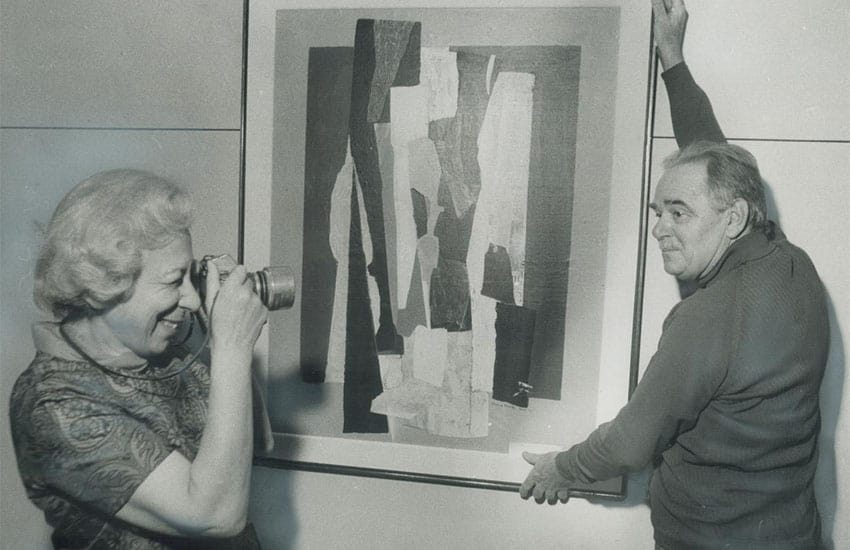

With the school sidelined, it was up to foreign artists who stayed and later retired in the decades that followed to build San Miguel’s current reputation as an artist’s town. Two important early pioneers in this effort were Leonard and Reva Brooks, who came in the late 1940s, and became promoters of San Miguel as an artistic haven.

Their efforts were timely since upcoming Mexican artists in the 1950s sought to leave muralism behind and embrace artistic styles with more international perspectives. The government’s and Mexico City’s near-absolute hold on artistic production loosened, allowing for ideas like abstraction, the establishment of private art galleries and a welcoming of foreign artists as equals rather than as apprentices to artists like Diego Rivera. The result has been a significant number of foreign artists living and working in Mexico since.

Perhaps the best way to describe the art market of San Miguel is to compare it to the No.1 Mexican market: Mexico City. Foreign artists have flocked to both for approximately the same length of time, but the kinds of artists, and their lifestyles, tend to be different.

Artists are attracted to Mexico City for its environment as one of the world’s largest cities, where one can be part of the next international art movement. Mexico’s avant-garde continues to be based there, but with a few exceptions like the Neo-Mexicanismo genre, the art produced there is part of global trends and tastes. Artists and buyers generally consider folkloric themes and even figurativism as “passé” or even going backwards artistically. The inspiration that artists get from the capital is not its mexicanidad but rather its status as one of the world’s major cities, like Paris or New York.

San Miguel, however, marches unapologetically to its own drummer. Sometimes derided as home to “artist wannabes” who never picked up a brush before retirement, a closer look reveals that the art scene there is more sophisticated.

Artists here range from novices and hobbyists to internationally known artists with long careers often both in San Miguel and abroad; one does not preclude the other. There is a cultural environment here that is matched only by much larger cities. San Miguel is able to attract internationally known writers, performing artists and much more, which bolsters the environment for visual artists.

Artist or not, many who live here couch their decision to settle in poetic terms, as longtime resident Mary Jane Miller states:

“It’s a mecca for people who are lost, who need a break, [who are] a little rough on the edges. It is a place of healing.”

It is also welcoming to a wide range of artistic styles, even those that no longer get a second glance elsewhere. This is because the art culture is embedded in a wider culture that’s a curious mix of the traditional pueblo (however idealized), tourist attraction, international chic destination and laid-back retirees’ haven. It also attracts others simply looking for something different.

The art market includes a significant chunk of people dedicated to depicting San Miguel itself, and rural/traditional Mexico in general, often inspired by the art of more than 100 years ago. Interestingly, this art appeals far more strongly to foreign buyers.

Art in San Miguel is also changing: some years ago, Mexico City residents began buying weekend homes in San Miguel, not because of its pueblo character but because of its international reputation. They have brought their “big city” art tastes with them, seeking out contemporary art, which galleries here have started to cater to.

A good example of how galleries are maintaining a balance between these two forces is the Galería San Francisco run by U.S. artist Susan Santiago. It includes a wide range of artistic styles — many appealing to those who wish to take a “piece of San Miguel/Mexico home,” wherever home happens to be. But it also has begun to offer more contemporary art for Mexican clients. Activities at the gallery range from classes for newbies (in multiple media), to judged art competitions registered with organizations such as the International Watercolor Society.

The historic center remains an important focal point for life in San Miguel, but for art, it has evolved to include a new venue: the Fábrica Aurora, the city’s old textile mill that has been converted to become a new cultural center, essentially a kind of “art mall.”

With traffic becoming horrendous in the downtown and many new developments popping up outside of it, the Fábrica was a stroke of genius: it features ample parking and yet is still walking distance from the historic center.

Santiago says one of its main appeals for customers is that you can spend a day comfortably under one roof, perusing the various galleries, restaurants and other offerings for an entire day.

San Miguel’s status as a tourist attraction also affects the art scene. Not only do visitors look for art to take home as a reminder of Mexico, the artists themselves are an attraction. Seven years ago, Arturo Aranda began taking tourists to visit the homes/workshops of selected artists here. The tours give potential buyers a peek behind the curtain, allowing them to meet the artist and see their lifestyle and production process.

One very successful stop is the workshop of Peruvian Ana Cornejo and Heinz Künzli, who make their own pigments, often from rocks they find biking in the area.

San Miguel’s art scene is unique because San Miguel itself is. It would not be what it is without its residents, both foreign and Mexican. There is no reason for this history not to continue, especially in the digital age when it is easier than ever to promote and sell all over the world.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.