A 1,600-year-old altar discovered in the heart of Tikal, Guatemala, offers striking evidence of the intricate and often contentious relationship between Maya society and the ancient metropolis of Teotihuacán.

According to a study published this week in the journal Antiquity, the altar wasn’t built by the local Maya, but rather by “foreigners” from Teotihuacán, located 1,500 kilometers away in what is now central Mexico.

Teotihuacán, known as “The City of the Gods,” was a sprawling area northeast of modern Mexico City renowned for its monumental pyramids, vibrant murals, and influential cultural and economic reach across Mesoamerica during its peak between 100 B.C. and A.D. 750.

Tikal was founded in 850 B.C. before ballooning into a dynasty around A.D. 100.

Guatemala’s Culture and Sports Ministry also announced the findings this week, detailing an altar adorned with vividly painted murals and linked to ritual sacrifices — which researchers say reshapes understanding of Mesoamerican power dynamics.

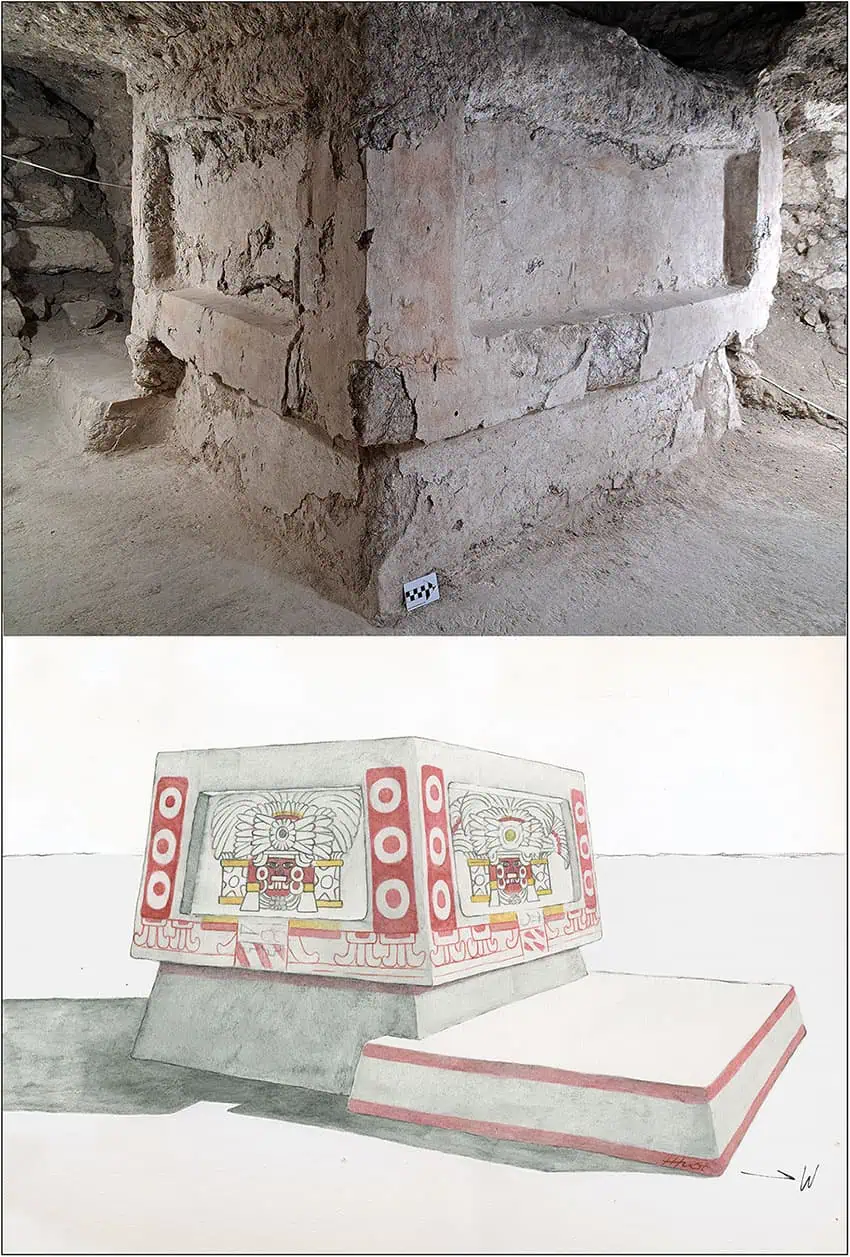

Buried beneath a residential complex in Tikal National Park, the 1-meter tall limestone altar features talud-tablero architecture (one inward-sloping panel topped by a perpendicular, rectangular panel) and painted panels depicting a deity resembling Teotihuacán’s “Storm God” or “Great Goddess.” The national park is located in northern Guatemala, less than 100 kilometers from the Mexican state of Campeche.

This figure, with almond-shaped eyes, a fanged nose bar and a feathered headdress flanked by shields, can be seen on four sides of the square piece. Archaeologists used advanced imaging technology to reveal its original red, yellow and blue pigments.

“What the altar confirms is that wealthy leaders from Teotihuacán came to Tikal and created replicas of the ritual facilities that would have existed in their home city,” said Stephen Houston, a professor at Brown University who was part of a global team of researchers who studied the altar. “This shows that Teotihuacán left a heavy imprint there.”

In an interview on National Public Radio (NPR), Andrew Scherer, another co-author of the study, said a central tenet of the research was trying to figure out just how heavy that imprint was.

“The growing sense of things is that rather than just a few folks coming down from central Mexico to sort of trade or interact at Tikal, they were more deeply embedded in the politics and the daily life, to the point that there were actually settlers who were sort of living permanently at Tikal,” said Scherer, a professor of anthropology, archaeology and the ancient world at Brown and director of the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology.

Built around A.D. 378, the altar coincides with a pivotal coup in Tikal’s history, when Teotihuacán elites deposed Tikal’s king, Chak Tok Ich’aak, and installed Yax Nuun Ahiin, whose father Spearthrower Owl was at least a noble, if not a king, in Teotihuacán. His installation is seen as a high point in Teotihuacán influence at Tikal.

Another sign was revealed in a Lidar scan in 2016: a scaled-down replica of Teotihuacán’s citadel near Tikal’s center, suggesting prolonged occupation before the coup.

“Teotihuacán saw the Maya region as a land of wealth — jade, feathers, cocoa — and sought to control it,” said Houston, a professor of social sciences, anthropology, and the history of art and architecture at Brown.

Hoy presentamos el Altar de estilo Teotihuacano de Tikal. Mañana saldrá la publicación en la revista científica Antiquity. https://t.co/Q0NHfeY53m

— Edwin Roman-Ramirez (@eroman378) April 7, 2025

Excavations around the altar, led by Guatemalan archaeologist Lorena Paiz, uncovered the remains of three children, all under age 4. One was interred in a seated position — a practice common in Teotihuacán but rare among the Maya — alongside a green obsidian dart point, a material emblematic of central Mexico.

Paiz said the altar was believed to have been used for sacrifices, “especially of children.”

Radiocarbon dating indicates the site was abandoned around A.D. 550–645, coinciding with Teotihuacán’s own decline.

The altar remains under guard, with no plans for public access.

With reports from Associated Press, NPR, La Jornada and Expansión