The destruction of an art installation by the city of San Luis Potosí (SLP) might just have a silver lining.

Marissa Martínez’s life is defined by a struggle to create art in an environment that is not the most conducive to it.

Born and raised in the state capital, her family talked her out of art and into business administration to make sure “she didn’t starve to death.” Although Martínez worked a “real job” for years, she took art classes and did whatever else she could to satisfy her need to create.

In 2000, she had the opportunity to travel to Barcelona where she first saw the trencadís (broken tile) artwork of Antón Gaudí. She found the technique fascinating, but absolutely no one in San Luis was doing anything like it.

So she began experimenting bit-by-bit on her own, using the walls of her parents’ (now her) home. Those very first experiments can still be seen in her workshop space today.

By 2015, she had learned enough about the technique, as well as efforts elsewhere that she organized her first community project in her home in the historic center, which opens into an alleyway called Callejón de la Yedra. A large section of it is defined by a wall belonging to an old ice factory, and she asked the owners for permission to create murals on it. Neighbors, young and old, came together to create a number of mostly religious images chosen by consensus, and many contributed their own resources to the project. It was such a success that it got coverage in the city newspaper.

At the same time, she got in touch with California philanthropist Dick Davis who has sponsored a number of mosaic mural projects in Mexico. He invited her to work on trencadís murals in California. He and the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo sponsored a visit by renowned tile artist Isaish Zeiger to San Luis Potosí. Together, they organized a project to cover one of the fountains in the city’s iconic Tangamanga Park II. Davis’ foundation also sponsored community murals in the nearby cities Matehuala and Ciudad de Maíz.

As much as she respects the work of her maestro, Zeiger, Martínez’s trajectory shows a progression away from his chaotic style of using whatever forms smashing tile with a hammer brings forth, to using more delicate nipping and grinding to control and smooth the pieces. This influence comes from the trencadís work done in Zacatlán, Puebla as well as Martínez’s preference for using Guanajuato talavera tile. Combining these two styles, Martínez has developed a style that is uniquely hers.

The community aspect of many trencadís mural projects is an important part of the more than 35 murals she has been involved with, which can be found in private residences, parks, schools, wineries and more.

Trencadís is labor-intensive, but much of the work is simple and repetitive, providing an opportunity for many to take part. Even before anyone touches a tool, the community gets a say in the design, meaning that those living in the area have a stake in the artwork and its preservation.

One of her biggest breaks was the commission to work on the facade of the psychiatry school of the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí. It breaks from her usual work, with the use of commercial tile and professional bricklayers, but the design, representing the seven ethics of the profession, is entirely hers. The university was attracted by mosaic work, not only for its appearance, but also because the building is in an industrial area, and prone to graffiti. To date, the work has resisted not only vandalism but also the city’s fierce sun.

However, there have been setbacks. When I visited Marissa in 2022, she told me that she heard that the Tangamanga fountain mural was in bad shape.

We drove out and were shocked by what we saw – entire sections were peeling off, with about half disappeared.

Wanting to save not only the work of her community, but that of an international artist, she organized an effort to get permission to restore the mural, but received no response. Instead, Martínez later found the fountain completely stripped of mosaic and painted over.

As great as this loss is, it may have benefits in the long run. The controversy over the mural’s fate brought publicity to trencadís and community-created murals. Martínez has received more requests to do murals and has more private art students (who pay the bills).

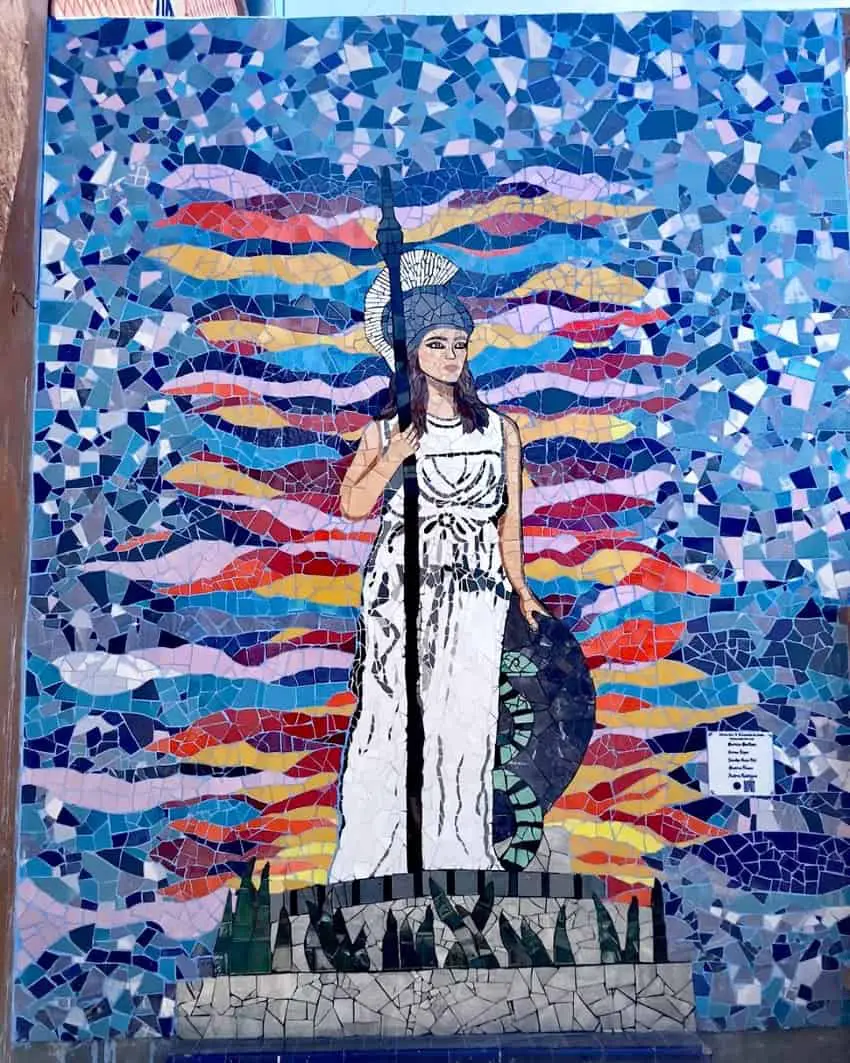

She has already done about ten projects since finding the ruined fountain. These include murals for the Cava Quintanilla winery, the Hospital Central, several in the house/museum of sculptor Joaquin Arias, (including a recreation of his famous Minerva statue of Guadajara) and one dedicated to the corn and bean cultivation of the small community of Estancita (Mexquitic).

Martínez’s projects have not been limited to Mexico, either. She created a mural at a home in Phoenix, Arizona. In California, she collaborated with U.S. artist Monica Meir to do “Butterflies are Free” in Carlsbad and “Homage to 49ers” in Alleghany.

All this gives her hope for more financial support for trencadís work in the future. There is no reason why tile murals in San Luis cannot experience the same artistic, civil and commercial success they have in Puebla, Puerto Vallarta and elsewhere. Such murals are particularly important, say Martínez, in areas that are being neglected as the city (and state) experiences accelerated growth, thanks to nearshoring investment.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.