So while visiting Tampico recently, a tour guide brought up “The Tampico Affair.” As a U.S. citizen, I smiled sheepishly, but he good-naturedly responded, “That was a long time ago.”

The events of April 1914 that he was referring to, when the United States invaded its southern neighbor, was Mexico’s fourth foreign invasion experienced in less than a century, 60 years after the U.S. invaded the port of Veracruz in March of 1847.

In 1914, Mexico was in the middle of the Mexican Revolution, and the U.S. was not neutral. Victoriano Huerta had seized power as a dictator, but his hold was tenuous. Forces under Venustiano Carranza were marching east to take the rich international oil port of Tampico. The U.S., looking to protect its citizens and interests there, backed Huerta at first, hoping he would bring stability.

But their stance on Huerta changed with incoming president Woodrow Wilson. Although Wilson had a reputation for pacifism, he would prove to be anything but in Mexico.

The U.S. invasion began with the Tampico Affair on April 9, 1914: the U.S. had several warships off the city’s riverside port to protect Americans working in the oil industry there, and their relationship with Huerta’s troops until then had been cordial. But these troops got nervous as Carranza closed in, and they restricted an area of the port where U.S. sailors had come to buy fuel.

When nine of the military men came for a routine purchase, they were arrested.

Local commander Colonel Ramón Hinojosa realized the gravity of this situation and reported it to his superior, General Morelos Zaragoza. All nine Americans were immediately ordered released, and diplomatic efforts were begun to appease the U.S.

It should have worked, but U.S. contingent commander Henry Mayo wanted more than an apology. Although both forces had previously performed ceremonial salutes to the other’s flags, Mayo demanded a 21-gun salute to the U.S. flag on Tampico soil as a concession — which, of course, the Mexicans refused.

The real problem was that Wilson sought to take advantage of the situation — and an incoming shipment of arms to the port of Veracruz — to try and get rid of Huerta. Wilson did ask Congress for permission to invade as the U.S. constitution requires, but he had already been shelling Veracruz for two days before he got it.

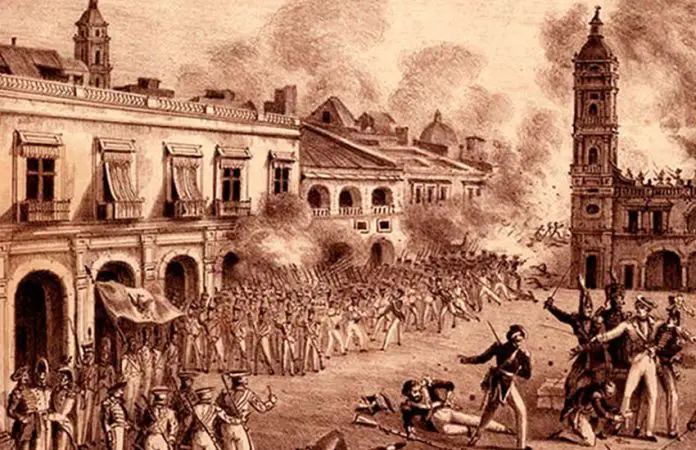

History books call the taking of the port the Battle of Veracruz. The original objectives were the port and the arms shipment.

Huerta’s army did not put up a fight. They were ordered to withdraw inland, as there were not enough of them to face the well-armed intruders. But before withdrawing, General Gustavo Maass handed out arms to the local population and even released prisoners to help residents form whatever defense they could.

The arms were of limited use given the small amount of ammunition handed out with them, and given the residents’ limited weapons knowledge. Despite this, locals (almost all civilians) did make life difficult for the invaders. Even those without arms threw stuff at them from balconies. Resistance was strongest at the local naval academy, where. Lt. José Azueta provided cover for retreating cadets, eventually losing his life to the cause.

Despite the bravery shown, the U.S. took the port in 24 hours with fewer than 100 casualties. The Mexicans lost about 500, mostly civilians. The U.S. soon realized that it could not hold the port without holding the rest of the city, which it took the following day, beginning an occupation that lasted until November 23, 1914.

Although militarily successful, the invasion and occupation became problematic for the U.S. government. Despite the fact that he was hated, Huerta’s support immediately increased as anti-Americanism grew not only in Mexico but also in the rest of Latin America.

Americans still in Tampico were abandoned as warships moved to south to support the invasion, and these foreigners eventually had to be evacuated, penniless.

These aforementioned problems the U.S. faced, and sporadic resistance to the occupation, eventually brought the Americans to the bargaining table. As Carranza was gaining strength, the U.S. succeeded in getting Huerta to step down, but it never got its 21-gun salute. As soon as Carranza took power, he reneged on the rest of the agreement until he, too, was overthrown.

Despite Carranza’s failings, he is still credited by historian Lester Langley and others of “…keeping the gringos out of Mexico City.”

The invasion would have repercussions for both countries for decades to come. The resistance of the local population consisted of street and guerrilla fighting, something unknown to U.S. regulars at the time. This experience is considered a foreshadowing of the kind of warfare that U.S. soldiers would encounter later in Germany, Vietnam and even Iraq.

Eager to sell the invasion to people at home, the U.S. bestowed an unprecedented Medals of Honor, but this caused scandal and reform to how this medal is awarded.

The problems didn’t absolutely convince Wilson to stay out of Mexico, however: he contemplated taking the Tampico oil fields and the ones in Tehuantepec in 1917, but Carranza ordered the fields destroyed if another invasion occurred.

In Mexico, a narrative of heroic resistance by the people against impossible odds began to take shape almost immediately. José Azueta and the fighting cadets became national heroes, with Azueta’s name still read as part of a ceremonial “roll call of honor” by Mexico’s armed forces. The naval academy was renamed the Heroic Naval Military School of Mexico for its resistance that day.

Meanwhile, the failure to fight meant that General Maass fell into obscurity, and this is one reason why Huerta is considered one of Mexican history’s villains.

The invasion kept Mexico neutral in WWI. Germany tried to take advantage of the rift with the Zimmerman Telegram, a secret proposal for Mexican support for the Kaiser in exchange for a later retaking of land from Texas to California. But Mexico declined.

More than 100 years later, the Mexican narrative of heroic civilian resistance remains important here: for the anniversary in 2014, newspapers like La Jornada criticized the government commemorations for not giving the local civilian resistance enough credit.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.