Put the two side-by-side and you might not believe they are related, never mind near-twins artistically: Antonio López Vega has a bohemian, almost-hippie look to him, while younger brother Jesús looks like an everyday local businessman. But both have been instrumental in Ajijic’s artistic history.

Born in the 1950s, the brothers grew up in a very different world. They were two of eleven children born to a trumpeter and carpenter and his wife in what was a rural village.

From a young age, both hustled to obtain resources for their family. Boys at that time roamed the lakeshore and mountains to collect firewood and find work helping local fishermen.

Jesús and Antonio came to know the area like the back of their hands, discovering petroglyphs and other pre-Hispanic artifacts, which fascinated them. This interest was bolstered by stories that their grandmothers and other elders told them of gods and legends of pre-Christian Chapala.

The most important legend related to the lake goddess Michicihualli and the culebra, a rare phenomenon when a waterspout rises up from the lake then smashes into a mountainside.

Such stories remain an integral part of their lives.

As idyllic as it sounds, such an environment is not exactly conducive to producing professional artists. But Ajijic had one unusual advantage: the relatively few foreign writers and artists that found their way here felt a sense of responsibility to the local population.

American Neill James founded several educational programs for children in the mid-20th century, but the most successful of them by far was a program of art classes. Jesús and Antonio were among the early graduates in the 1970s and two of the reasons why Ajijic’s mural scene is still dominated by local painters.

Some of James’ graduates, like Jesús, were able to start careers with what they learned from her program. Others, like Antonio, received scholarships to study art at what is now called the Instituto Allende in San Miguel de Allende in Guanajuato.

There, Antonio earned a degree in art, which led to a position sketching archaeological work at Chichén Itzá in the early 1980s. Afterward, he went to Mexico City, where he survived selling his work on the street. An award from the Salón Nacional got the attention of galleries and museums, as well as a stint teaching back in San Miguel de Allende. But before the end of the decade, he was homesick and returned to Ajijic.

The two brothers’ lifetimes are strongly marked by the massive changes that the Lake Chapala area has experienced. Their memories include the construction of the main highway on the north shore, as well as the massive influx of foreigners since. They also remember the introduction of electricity, which they remember met with some resistance as residents did not like being unable to see the night sky.

Interestingly, neither expressed animosity to foreigners directly to me, and a fluent Jesús even offered to do the interview in English.

The aim of the brothers’ work is to preserve the essence of their childhood Chapala, using surrealist and allegorical imagery, rather than landscapes or other realism (a la Diego Rivera). Their differences come in each brother’s execution. Jesús’ work is a little more naïve, often with a halo effect around his figures. Antonio’s show various influences from his time in academia and other parts of Mexico.

Both work in various media: metal etching, wood and stone sculpture and ceramics, but their most influential work is on canvas and murals in the Chapala area.

Jesús is behind one of Ajijic’s most impressive, multifaceted murals, “Birth of Teo-Michin-Cihualli,” situated in the stairwell of the town’s cultural center. It features the lake goddess in various aspects, along with several figures from Mexico’s history. Antonio’s “Mural Dedicated to Water” can be seen along a stretch of the north shore highway.

Both have works in collections all over the world, thanks to Ajijic’s international population, but Antonio’s work has more reach in Mexico.

Both have a passion for research, artifacts and documentation. They started with the stories from their childhood, as Jesús notes that “… fewer local families are passing down oral tradition to their children.”

They believe that the stories are also important to foreign residents, so that “…they can appreciate the area in which they live as a unique and vibrant place,” Jesús says.

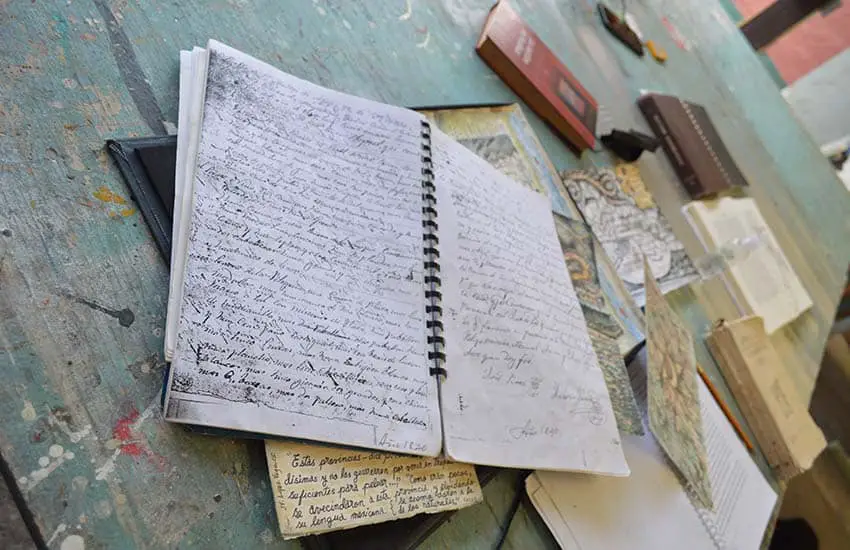

Jésus has been working for years on a project to document both the indigenous and Spanish foundations of Ajijic, with an eye toward the town’s 500th anniversary in 2031.

The brothers’ documentation efforts are a combination of academic text, fiction, poetry, illustration and painting. They are even producing their own artisanal books.

They have also collected artifacts in the region, particularly concerned about the petroglyphs they discovered as children. As land development takes over more of the mountains, “… The rocks become ‘trapped’ on private property and become little more than ornamentation for owners instead of community heritage,” Antonio says.

One piece that has been rescued is Tepayotzin (“sacred turtle rock” in Nahuatl), now available to the public on Ajijic’s boardwalk.

Despite all their similarities, the two men work separately in different environments. Neither inherited their parents’ property. Jesús lives and works in his Galería de Arte Axixic on the west end of town. Antonio lives at the semi-communal La Cochera Cultural Center, where he found refuge after coming back to Ajijic.

Both appreciate the opportunities that James’ program gave them and pay it forward. Jesús teaches with the same program, now sponsored by the Lake Chapala Society. Antonio set up classes at La Cochera, focusing on children in neighborhoods in the mountains.

Although both are successful at a time when art is booming in Ajijic, it is still difficult to make a living as more artists move in and compete for the attention and money of the same tourists and foreign residents.

The brothers’ work not only maintains the prestige of Ajijic art, it also serves as a reminder of the community’s heritage as chaotic development establishes ever-more gated communities, specialty stores and restaurants here, increasing the area’s cosmopolitan and international flair.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.