Almost 180 years before Barack Obama was elected the first Black president of the United States, Vicente Guerrero became the first Black president of Mexico. Vicente Ramón Guerrero Saldaña was born in 1782 to an Indigenous mother and African-Mexican father. His presidency was short-lived, lasting only 260 days, but in that short time, he abolished slavery throughout Mexico.

Described by contemporaries as “bronze-faced, tall and strapping,” Guerrero was one of the leading insurgent generals during the War of Independence. Guerrero enlisted in José María Morelos’ army in southern Mexico in December 1810. After the executions of Miguel Hidalgo in 1811 and Morelos in 1815, Guerrero emerged as the visible leader in the War of Independence. In February 1821, seeing that conditions could favor the flagging insurgent cause, Guerrero combined his forces with those of royalist leader Agustín de Iturbide. Their combined army entered Mexico City in triumph on September 27.

The first 30 years following independence were turbulent, with heads of state coming and going in rapid succession: 49 presidencies between 1824 and 1857. Guadalupe Victoria, the first president of Mexico, was the only president to complete his full four-year term. Victoria came to power by overthrowing Iturbide’s Mexican Empire, Mexico’s first independent government, alongside other military leaders, including Guerrero.

Freemasonry was an important social force in the early republic. In the 1828 election to succeed Victoria as president, the Scottish Rite and the York Rite were the de facto political parties. Guerrero was the candidate of the liberal York Rite. At the same time, Manuel Gómez Pedraza – who had been a staunch royalist until the very end of the independence struggle and a supporter of the First Empire – ran as the candidate of the “Scots.”

Vicente Guerrero’s short presidency

Pedraza won, with Guerrero coming in second in an indirect election by state legislatures. But Guerrero’s supporters accused Pedraza, Minister of War under President Victoria, of using the military to influence the election. Two weeks after the election, Antonio López de Santa Anna – governor of Veracruz and a former officer in the War of Independence – called for nullifying Pedraza’s election and declaring Guerrero president.

In November of 1828, Guerrero’s supporters marched into Mexico City and violence erupted. President-elect Pedraza resigned and fled to England, and Guerrero became president. The third-place runner up in the election, a conservative former royalist military officer named Anastasio Bustamante, became Guerrero’s vice president.

Guerrero, who was seen as a liberal hero of the independence and was visibly mixed-race, represented a step towards empowering Mexico’s Indigenous, mixed-race, and Black majority, which alarmed the criollo aristocracy.

Abolishing slavery in Mexico

Although several states had abolished slavery upon independence, Guerrero took it a step further and abolished the condition of slavery throughout Mexico. On September 15, 1829 – 34 years before Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation – Guerrero issued a decree that slavery was abolished in the Republic of Mexico and that those who had been enslaved were now free.

Several months later, in December, Guerrero was deposed by a rebellion led by Bustamante. He fled south to assemble troops to fight the rebellion but was captured in Acapulco by a Genovese merchant ship captain, Francisco Picaluga, and was paid 50,000 pesos for his role in the coup plot. Picaluga turned Guerrero over to federal troops in Oaxaca, where he was court-martialed and executed by firing squad in the town of Cuilapan.

Historian Juan Ortiz Escamilla writes that “Guerrero’s government was discredited not because he headed a supposedly ‘illegitimate’ government but because he was Black; ‘Black Guerrero,’ as the Mexico City aristocracy pejoratively referred to him. They hated him because they were segregationists and because he impeded the preservation of their rights. They killed him in a bold-faced act of racism.”

Abolishing slavery in Mexico opened a new route to freedom for people escaping slavery in the U.S., especially those in Texas and Louisiana. Historian Alice Baumgartner, author of the groundbreaking 2020 book “South to Freedom: Runaway Slaves to Mexico and the Road to the Civil War,” estimates that thousands of enslaved people reached freedom in Mexico.

A haven for escapees from slavery

Some enslaved people received help from the loosely organized Underground Railroad to Mexico, composed of free Black people, abolitionists, Mexicans, Germans, preachers, ship and barge captains and even mail carriers.

Many runaways used their own ingenuity – acquiring forged travel passes, they disguised themselves as white men and women. For the enslaved in Texas and Louisiana, the northern states were hundreds of miles away, and even if they managed to cross the Mason-Dixon line, they were not truly free. Under the Fugitive Slave Act, fugitive slaves could be captured and returned to their enslavers.

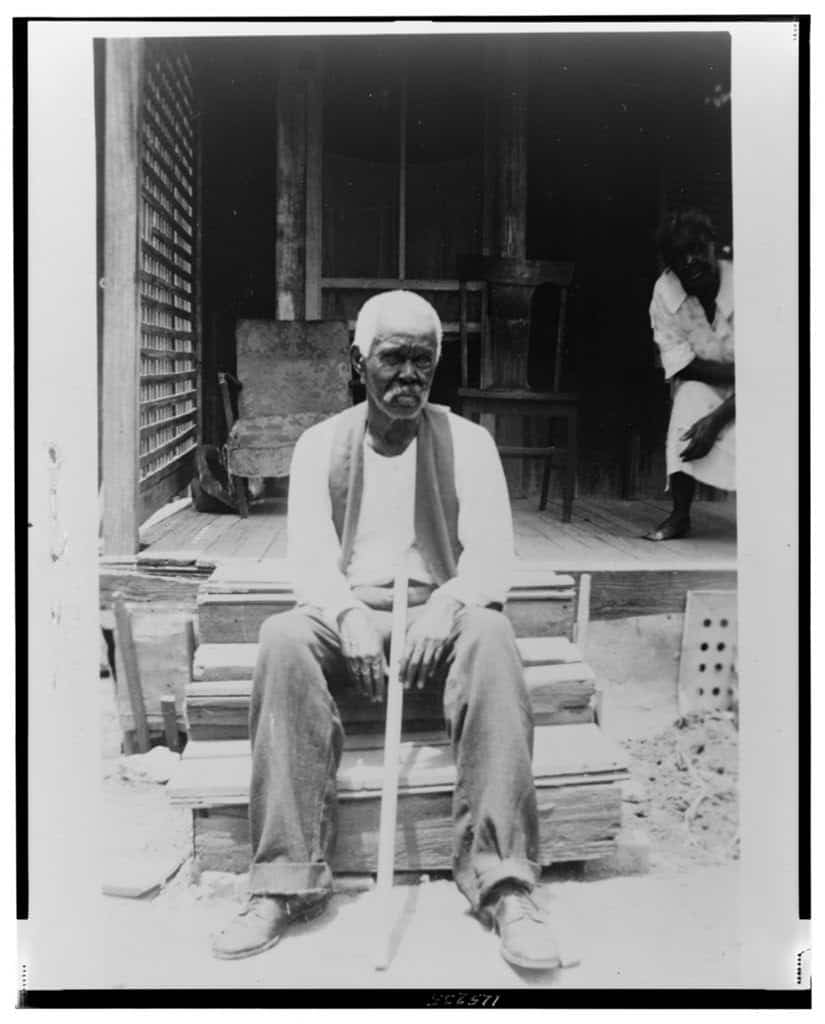

Felix Haywood was born into slavery in St. Hedwig, Texas, in 1844. Interviewed for the federal Slave Narrative Project in 1936 at the age of 92, he recalled that others would sometimes “come ’long and tell us we should run up North to be free. We used to laugh at that. There wasn’t no reason to run up North. All we had to do was walk, but walk South, and we’d be free as soon as we crossed the Rio Grande. In Mexico you could be free. They didn’t care what you was, black, white, yellow, or blue. Hundreds of slaves did go to Mexico and got on all right. We would hear about ‘em and how they was goin’ to be Mexicans. They brought up their children to speak only Mexican.”

In an interview, Kyle Ainsworth, Project Manager of the Texas Runaway Slave Project at Stephen F. Austin State University, which documents and archives records of slaves who escaped to Mexico, says, “I am constantly amazed by the courage of runaways… inevitably every escape required that runaway slaves take risks with uncertain outcomes. That so many made it to Mexico is a testament to their desire for freedom and a better life.”

Along the banks of the Rio Grande, abolitionists like Nathaniel Jackson and John Webber had ranches that provided refuge as they assisted escapees from slavery in getting to Mexico. Jackson, a loyal Unionist, left Alabama in the 1850s with his African-American wife Matilda and their children to escape the intolerance of interracial marriage. Founding a ranch on the Rio Grande in Texas he became part of the underground railroad to Mexico.

John Webber was a white settler who fell in love with Silvia Hector, an enslaved woman. He purchased her freedom and the freedom of her children from his business partner and moved to the Rio Grande Valley just down from Jackson and his wife. Webber would ferry runaways across the Rio Grande to freedom. Both families were well known in the clandestine network of runaways and abolitionists.

Once in Mexico, the runaways were protected. Baumgartner says, “The evidence that Mexican officials and citizens protected freedom seekers comes from various sources—municipal records in Mexico, legal documents from cases in which U.S. citizens were arrested for attempting to kidnap fugitive slaves and Mexican military records.”

American diplomats pressured Mexico to sign an extradition treaty to return the runaway slaves to their owners, but Mexico flatly refused each time – in 1850, 1851, 1853, and 1857.

“Mexico actually contributed to global debates about slavery and freedom and is rarely given credit for its role in providing a safe haven for runaway slaves. The enslaved people who escaped from the United States and the Mexican citizens who protected them ensured that the promise of freedom in Mexico was significant,” Baumgartner says.

As president, Guerrero championed the causes of the racially and economically oppressed. He has been honored as a folk hero of the War of Independence. However, his role in ending slavery was his greatest achievement as president and its impact on escapees from slavery in the United States is now being recognized.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive, researcher, writer, and editor. She has been writing professionally for 35 years. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing. She can be reached at AuthorSherylLosser@gmail.com