A soldier wearing a black balaclava took my passport and looked me over. He was guarding the only entrance to the village of Oventic, Chiapas, which remains under the control of the ultra-leftist revolutionary group known as the Zapatistas.

It took me about an hour through the misty mountains of the dense Lacandon jungle to get here from San Cristóbal de las Casas. I noticed a rifle hanging from the guard’s shoulder. Visitors were apparently welcome in this caracol (Zapatista-controlled town), albeit under close supervision from guides who provided little to no information about the militarized anti-capitalist group controlling it.

It was my first dose of ”Zapatourism” four years ago — just a few days before a gathering scheduled to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) uprising in the mid-1990s that eventually grew into a powerful political movement.

If you’re too young to remember, in 1994, Zapatista forces took over several towns in the state of Chiapas, including San Cristóbal, before Mexican troops retaliated, leading to a series of bloody battles.

Within 48 hours of occupying San Cristóbal, this group of indigenous farmers and laborers turned guerrilla fighters had declared war on the Mexican government from the balcony of the city’s municipal palace.

The armed conflict — centered on Indigenous grievances regarding centuries of inequality, racism and exploitation — lasted fewer than two weeks before a local bishop, Samuel Ruiz García, brokered a peace between the EZLN and the federal government. But it transformed the Zapatistas into a well-known social movement still influencing leftist organizations today.

Once swaths of Chiapas ended up under the EZLN’s unofficial control, the group then turned its attention towards establishing an alternative autonomous system of governance and began to take on new values. Indigenous communities previously isolated from mainstream education, healthcare and justice have made huge strides under the Zapatista regime, and others have joined on the back of that success.

In these communities, women are leaders, soldiers and organizers alongside men, considered equals. Children are taught to take pride in their ancient Indigenous heritage. Each community works as a unit to keep people fed, clothed and educated and to keep their community safe. Zapatista communities work together to help each other thrive.

This was what I came to see. And I was not alone. The unique system has piqued the interest of thousands of tourists who flock to Chiapas to see how an alternative political model can function outside conventional governance.

I also came to see what the Zapatistas would have to say for themselves 25 years after their uprising.

When I arrived at Oventic, the guard questioned my intentions before ushering me and two other visitors through the community’s gate. The ground rules: no pictures of people; remain with the guide at all times; you may be moved without warning if there is trouble.

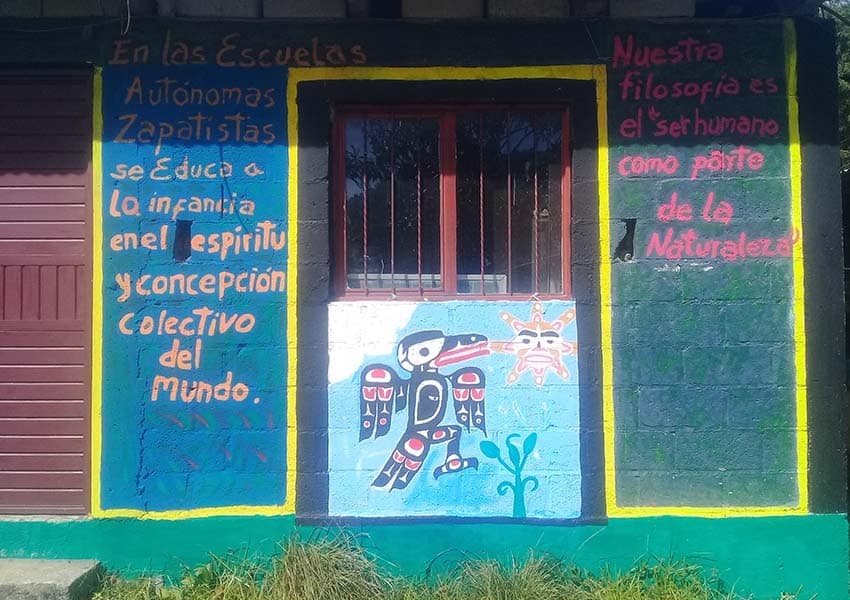

This town has a single straight road curling into a spiral at its base, to resemble a snail (caracol), an animal that has links to Mayan mythology. Wooden huts here are adorned with revolutionary murals depicting the teachings of residents’ ancestors, as well as abstract anti-capitalist propaganda.

Heroes of the movement such as Subcomandante Marcos or Subcommander Ramona are glorified in artistic images of liberation while industry and major corporations are demonized. I learned later that Zapatista schoolchildren are fed these ideologies alongside core subjects like mathematics, sciences and languages. I thought it bordered between enlightenment and indoctrination.

From Oventic, it was an eight-hour drive to La Realidad, another caracol deep inside the Lacandon jungle. The planned three-day Zapatista celebrations would conclude on New Year’s Day, the exact anniversary of the uprising two and a half decades ago.

It was clear they were planning something big for this celebration. Why else would they have invited foreigners into their normally closed-off experimental autonomous villages?

Curious, I hitched a ride with a group of Zapatista supporters staying at the same hostel, which included a mix of French and urban Mexican anarchists.

At a campsite several miles from La Realidad that was designated for several hundred Zapatista supporters and Zapatourists, I felt bemused by the festival atmosphere: despite the fact that unarmed EZLN soldiers in full uniform and black ski masks patrolled the periphery incessantly, I half-expected someone to start juggling among the colorful assortment of pitched tents.

But once the meetings commenced, I saw how serious organizers were about the agendas at each table, or mesas, the name given to debate circles. A mesa exclusive to women caught my eye; it discussed progressive feminist topics and how they could be applied under the Zapatista regime.

It was surprising, however, the number of mainstream leftist arguments I found filtering into the discussions about topics affecting the lives of small Indigenous Mayan communities in Chiapas. Ideologies ranging from using inoffensive pronouns in speech to not drinking Coca-Cola because of a belief it embodies capitalism seemed of little use to the people in these Indigenous communities.

Then it was New Year’s Eve: it was time for visitors to pack up their things and to finally set up camp at La Realidad, where the celebratory grand revelation would occur the following day. It was the sole reason for most people to attend the gathering — to see what declaration the Zapatista leadership would make on the 25th anniversary of its uprising.

A call for all visitors to make their way to the main square blasted from loudspeakers attached to long wooden poles towering over the village. Soon we were surrounded by soldiers who formed a tight perimeter to box us in. The show was about to start.

The opening act was the legendary figure of the movement: Subcomandante Marcos, a university professor from Tamaulipas. Bearing his signature pipe and pot belly, he casually strolled toward the stage.

Regiments that had fought in the battle of San Cristóbal joined a new generation of foot soldiers who filled the plaza in a sea of the Zapatista colors: green, red and black. The ‘clack, clack’ sound of troops striking wooden batons as they marched into position must have felt like a single beating heart to the onlookers who stood in silent awe.

When it abruptly stopped, the audience seemed to hold its breath, as if waiting for the Zapatista declaration’s first words to enter the world.

Basically, we heard a warning that the ongoing construction of the Maya Train — and incursion into Zapatista territory — would be met with force; such incursion has not yet happened.

In the end, it appeared that the whole affair became an ideal exchange between the Zapatistas, the curious international media and Zapatourists, who pump plenty of dollars directly into the movement.

Mark Viales writes for Mexico News Daily.