With a scythe, a long robe and piercing stare, this figure looks very much like the Grim Reaper icon we know from film, books and other media. However, this version is more: it’s a religion and a split in how Mexicans see death.

With the name of Santa Muerte — which can be translated as “Saint Death” or “Holy Death” — the figure is considered female, not male. Alternate names include The White Girl, La Flaquita (little thin one), and perhaps most interestingly, The Virgin of the Forgotten.

Religious studies professor R. Andrew Chestnut of Virginia Commonwealth University, author of “Devoted to Death: Sante Muerte, the Skeleton Saint,” published by Oxford University Press, says that Santa Muerte has 12 million followers in Mexico alone, and it’s rapidly gaining followers in the U.S. and in other parts of Latin America.

Her popularity in Mexico may not seem strange for a country famous for Day of the Dead, but Santa Muerte’s existence is nonetheless controversial.

“Ground Zero” for Santa Muerte is undoubtedly Mexico City, more specifically the neighborhood of Tepito, the quintessential example of a Mexican rough neighborhood.

Just over two decades ago, a woman named Enriqueta Romero — better known as Doña Queta — decided to go public with her faith in Santa Muerte and erected a shrine to her outside her house in Tepito, both as a testament and as a place for the faithful to gather.

Today, on the first of every month, thousands of the faithful gather on the streets around the house to approach the shrine, often carrying their own Santa Muerte statues in a myriad of colors and sizes and bearing their own accouterments.

Shrines to Santa Muerte have since proliferated all over Mexico City’s poor neighborhoods, including others in Tepito. Some are notable in their own right, such such as one in the Doctores neighborhood, where Santa Muerte shares space with the “narco-saint” Jesús Malverde. In the conjoining city of Tultitlán, there is a Temple of Santa Muerte with a 22-meter-tall image.

Outside the capital, one of the most interesting Santa Muerte sites is a seemingly out-of-place “church” and museum complex just outside Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, in the town of Santa Ana Chapitiro. It attracts pilgrims from all over Michoacán and beyond.

Santa Muerte seems to have exploded from out of nowhere. Doña Queta claims the faith goes back generations but that worshippers had to keep hidden until about 20 to 30 years ago. Neither its practitioners nor academics agree on its origin or history.

Most agree that it is a syncretism of Mesoamerican and Catholic beliefs, sometimes with elements from Afro-Caribbean religions. Folk histories attribute it to a healer/witch from the eastern part of Mexico (some say Puebla, others Veracruz) who lived sometime in the 19th or 20th centuries.

Skeletal imagery has played a significant role in Mexico’s culture from the Mesoamerican period to the present, from Mictlantecuhtli (god of the underworld) to San Pascualito Rey (still venerated in Chiapas) to La Catrina. Some academics put the origin of Santa Muerte to Veracruz because of its history of worshiping skeletons. But there is no documentation to prove lineage, only tantalizing similarities.

However, the modern-day Santa Muerte is nearly an exact replica of the Western personification of death, and her rituals nearly the same as those offered to any “normal” saint — rosaries, pilgrimages, offerings and even the practice of approaching the shrine in Tepito on one’s knees (an act of piety and humility famously associated with the Virgin of Guadalupe).

Differences are subtle, such as the offerings of cigarettes and alcohol and other indications of the rough life that most believers live.

In addition, the religion is rapidly evolving and diversifying with no central canon. Her “patron saint day” can be August 1, August 15 and even December 13.

The trappings of Catholicism involved is one reason why the Vatican repeatedly condemns Santa Muerte, stating in no uncertain terms that it is Satanic and associated with black magic. But most worshipers do not consider their use of Catholic rituals as mockery, nor do they consider the figure as a personification of evil

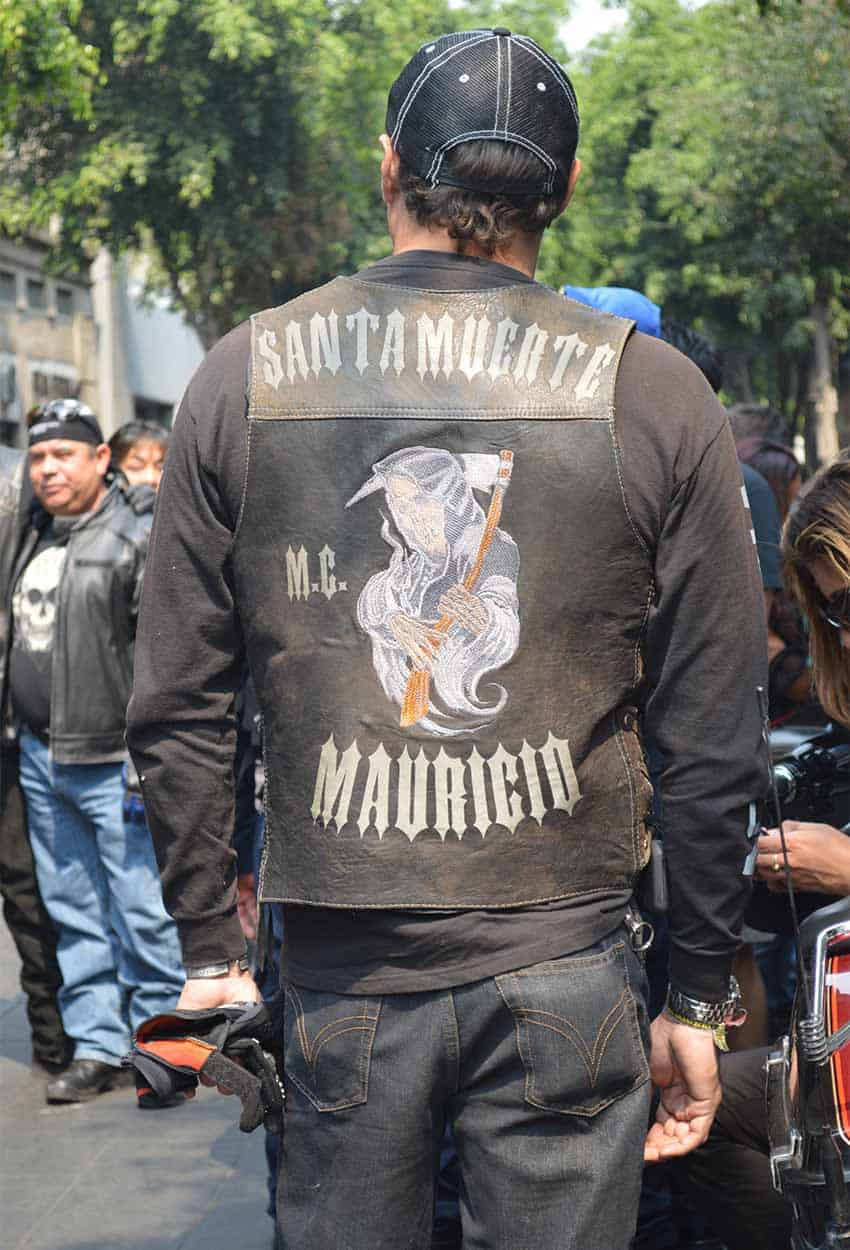

The other issue is her strong association with (often organized) crime and those who live with violence everyday. Romero acknowledges that many in front of her house are delinquents.

“I do not involve myself in their lives,” she says. “Are there thieves that pray? Yes, everyone is here, and it is not for me to judge.”

She emphasizes that there are good people who believe in her as well as criminals and that they should not be judged by the actions of others.

But perhaps the greatest challenge of Santa Muerte to the Church is its metaphysics: Christianity essentially exhorts its followers to eschew the world and focus on a reward to be found after death. Time on earth should be spent on “getting right with God” so that when we die, we can enjoy what life denied us.

But many of Santa Muerte’s followers see themselves trapped in a reality that will not allow them to approach God, especially since the Church requires itself to be an intercessor. So these faithful are “forgotten” by the Church, assured only of death, not of redemption. Instead, they think, it’s best for them to focus on today’s needs and desires because perhaps they can get a small favor here and there, rather than a big reward at the end.

Santa Muerte is inclusive since Death does not discriminate. She will “hear” petitions for “difficult things” (crime), but she also appeals to police officers, who also deal with crime and violence everyday. She even appeals to some in Mexico’s upper classes, who live with the reality of becoming victims of kidnapping and extortion.

For Tepito, Santa Muerte is not part of the community’s identity, and Romero considers attempts to return faith in her to traditional religion to be “invasive.”

“The other day, a gringo came to yell at us about the ‘true faith,’” she said, adding something unprintable about how they threw the invader out.

And not all Mexicans are enamored with this “new” relationship with Death — many are still Catholic, or at least see the Church as part of their identity. In 2022, one man in Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas, went as far as to burn down a Santa Muerte shrine, stating he was acting “under God’s orders.”

But for many believers, Santa Muerte is a comfort in the face of harsh realities of life at the margins of Mexican society — where mainstream religion’s promise of a heavenly reward for good behavior breaks down among a host of contradictions.

“I do not know where we go after we die,” Romero says. “My faith helps me to survive today. I do believe in God as well as my Flaca. If tomorrow comes, well, it’s another day, and that is a reward.”

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.